Anti-Jewish riots in the 18th century

Jewish emancipation and violent protest in Hamburg

Harbingers of political antisemitism after 1848

Antisemitism as a political-social movement

The radicalization of antisemitism after World War I

Intensification of the antisemitic climate during the Great Depression

State-sponsored antisemitism 1933–1938: marginalization and plundering

Antisemitism in the postwar period

Beginning at the end of the 18th century, the spreading idea of human rights, the new, Enlightenment-era way of thinking about the state, and the social change from a corporative society divided into estates to a bourgeois-capitalist society led to a demand for social integration of the Jews in all European states. As a legally autonomous corporation, their position in society was that of outsiders. From the beginning, legal equality for Jews was opposed by many social groups. Aside from traditional religious and economic motives, cultural, nationalist, and proto-racist arguments were used early on in order to fight – sometimes violently – legal equality for Jews. This form of hostility against Jews intensified in the course of the crises caused by social and cultural changes in the second half of the 19th century and eventually took the shape of a social and political movement bearing the new name of antisemitism. Although antisemitic parties and organizations remained politically marginal in Imperial Germany, they did manage to establish antisemitic ideology in certain social milieus.

The First World War and its immediate postwar consequences (revolution, a new political system, the Treaty of Versailles) shifted radicalized antisemitism from the periphery to the Weimar Republic’s political center, where it combined with an unscrupulous and often violent fight against the democracy defamed as a “Jew republic” [Judenrepublik]. Anti-Jewish hostility took on increasingly extreme forms in the early 1930s until it led to complete disenfranchisement and social ostracism and eventually to the murder of the European Jews during the National Socialist regime. “Antisemitism after Auschwitz” picked up on themes of earlier antisemitism and also added some new motifs such as guilt-denying antisemitism [Schuldabwehr-Antisemitismus], which denies events or rejects responsibility for them. After the founding of the state of Israel, antisemitism first arose in the Eastern bloc states and, after the Six-Day War of 1967, also in the West where it took the form of criticism of Israel and anti-Zionism.

The history of Hamburg, one of the centers of Jewish life in Germany since the 17th / 18th century, reflects the phases of anti-Jewish hostility outlined above. At the same time, both the senate and the city assembly had long promoted the Jews’ social integration since they played an important role for this port and merchant city and its overseas trade due to their international connections. Even before debates on legal emancipation began, there had been disputes between the city council and church orthodoxy about the presence of Jews in the city, in the course of which the Jews repeatedly bore the brunt of unfolding social conflicts. There were violent riots out of protest against legal concessions to the Jews, such as the 1730 “Judentumult” (“Geseroth Henkelpöttche”) in Hamburg’s Neustadt [New Town] which again became the scene of anti-Jewish violence in 1746 and 1749.

Since the end of the 18th century, the new definition of the Jews’ social position necessitated by political and economic reforms such as religious freedom and equality for all citizens (in Hamburg in 1819), freedom of trade, the removal of economic barriers, the establishment of a state-run school system, compulsory military service, and the right of domicile led to a decades-long dispute which was fought in parliamentary debates, writings, but also by means of violent protest. Until the Jews’ complete and nationwide legal equality in 1871, the process of emancipation was characterized by a zigzagging between legal improvement and setbacks. The period of emancipation saw repeated anti-Jewish riots which were an expression of opposition to the granting of civic rights and the economic opportunities for Jews associated with it. The Jews had gained full equality in 1806 after Hamburg was conquered by Napoleonic troops, but the fall of Napoleon prompted a battle for the revision of these “more liberal laws for Jews” which was fought in a number of publications. Ludwig Holst, who since 1799 had made a name for himself in Hamburg as an economic expert, in his 1818 pamphlet “Über das Verhältniß der Juden zu den Christen in den deutschen Handelsstädten” [“On the Relationship of the Jews to the Christians in German Merchant Cities”] warned of the “social agitation” caused by the Jews’ economic success and demographic growth, which might end in a “loud outrage.” In another book published in 1821, Holst blamed the Jews’ economic power for the financial problems craftsmen and middle-class merchants were experiencing at the time. In the time between Holst’s two publications, the wave of anti-Jewish “Hep-Hep”-riots originating in Würzburg in the summer of 1819 reached Hamburg, where riots broke out when Jewish patrons visited cafés in the pavilions along the Binnenalster, which was considered both a transgression of bourgeois social dividing lines and a presumptuous claim of social rights. The riots spread to other parts of the city and could only be ended by mobilizing the citizens’ militia and declaring a state of emergency. Hamburg’s upper classes supported the civic emancipation of the Jews while its opponents, craftsmen and members of the retailers’ guild, feared Jewish competition in the trades and commerce. The senate used the riots in order to postpone the granting of full civic rights to the Jews by blaming them in part. Members of the Jewish community consequently left Hamburg for Altona.

Brawl between Jews and Christians during the anti-Jewish riots in Hamburg

1835

Source: State Archive Hamburg,

720-1, 220-1.

The causes of the anti-Jewish riots of 1830 and 1835 hardly differed from those in 1819. Craftsmen and retailers organized in guilds felt threatened by the lowering of import tariffs, debates on legal reform concerning the structure of guilds, a new decree on servitude [Gesindeordnung], and a reform of the citizenship law. In 1834 a group of Jews around Gabriel Riesser had demanded full legal equality including freedom of trade for Jews in Hamburg in a publication titled “Denkschrift über die bürgerlichen Verhältnisse der Hamburgischen Israeliten” [“Memorandum on the Civic Circumstances of Hamburg’s Israelites”]. The protesters’ criticism shows that when the Jews were made “scapegoats” for their displeasure with senate politics, they were not picked out randomly, but were seen as a politically favored group of foreign elements steadily growing through migration. Thus the 1835 riots can be seen as an ultimately successful attempt to prevent further emancipation of the Jews. Despite attempts to incite the lower classes in particular to riot against Jewish merchants, Hamburg remained unaffected by the social protests triggered by the 1848 revolution. However, on May 13, 1848, the Hamburg suburb of St. Pauli did become the scene of riots which originated mostly among craftsmen and retailers.

Despite the turn towards restoration after the failed revolution of 1848, a burgeoning economic and political liberalism created a political climate which favored complete legal emancipation of the Jews. In Hamburg it did not occur until 1860, however. Now it was former leftists and liberals such as Richard Wagner or Bruno Bauer who, disappointed by what they considered the Jews’ lacking willingness to assimilate despite emancipation, emerged as authors of anti-Jewish publications. Among them was politician and journalist Wilhelm Marr, who was later dubbed the “father of the antisemitic movement.” In Hamburg, too, Jewish emancipation became a point of contention in the emerging political rivalry between “liberals” and “radicals” after 1848. In his 1862 publication “Der Judenspiegel” [“A Mirror to the Jews”], the “radical” Marr presented a negative image of Judaism and accused reformed Jews of having renounced political reform. The fact that the political climate in Hamburg was contrary to Marr’s position becomes evident in the publication of the satirical broadsheet “Der Judenfresser” [“The Jew Eater”] in June 1862 as well as in the outrage against Marr among Hamburg’s political circles.

With the onset of the economic crisis of the early 1870s known as “Gründerkrach”, the atmosphere in the newly founded German Kaiserreich started to change. Reich Chancellor Bismarck reacted with a protectionist economic policy and changed his political course to join the conservative camp. As supporters of liberalism and Social Democracy, the Jews now found themselves on the side of the political enemy. They were accused of being responsible for the economic crisis and the ever more pressing “social question.” The antisemitic movement had its origins in Berlin; in Hamburg both the city’s political circles and the merchant class, who continued to support liberalism and free trade, remained aloof towards it. It was not until the 1890s that some of its citizens’ associations began to respond to political antisemitism. In 1893, delegates of the German Social Party Deutsch-Soziale Partei were elected to Hamburg’s city assembly, and in 1897 an Antisemitic Voters Association Antisemitischer Wahlverein was founded in response to the Christian-social movement founded by Berlin court chaplain Adolf Stoecker. Its first chairman was Friedrich Raab, a delegate to the city assembly as well as the Reichstag, where he represented the antisemitic Deutsch-soziale Reformpartei from 1898 until 1903.

In this phase antisemitism mainly met with support from craftsmen who felt insecure due to the dissolution of their corporative ties and the challenges posed by a capitalist market economy and who saw the Jews as responsible for their plight. The new profession of retail clerks, who had created their own special interest group in 1893 by founding the German Union of Commercial Employees “Deutscher Handlungsgehülfen-Verband (named German National Union of Commercial Employees Deutschnationaler Handlungsgehilfen-Verband, DHV as of 1896) in Hamburg, took its lead from the nationalist and antisemitic movement and refused membership to Jews. As a “national labor union” the DHV opposed Social Democracy, which it considered “antinational,” as well as “Jewish High Finance.” The DHV owned the Hanseatische Verlagsanstalt publishing house, which served as its forum for spreading nationalist-antisemitic writings. After 1900 the DHV supported antisemitic parties and associations both personally and financially. Hamburg became home to one of the most active antisemitic agitators of the time, Afred Roth, who worked as officer in charge of education and social affairs at Hamburg’s DHV headquarters from 1900 until 1917 and was one of the driving forces behind the founding of the German Nationalist Protection and Defiance Federation, (DVSTB) Deutschvölkischer Schutz-und Trutzbund, in 1919.

Military defeat, fear of revolution, economic collapse, and the brutalization of political life all led to an unprecedented mobilization of antisemitism in Germany. It found its expression in writings, public agitation, and violent riots and allied itself with the fight against the Weimar Republic defamed as a “Jew republic” [Judenrepublik] by antisemites. Indeed, Jews were able for the first time to hold major political office in this new democratic state, such as Walther Rathenau as foreign minister, Hugo Preuß as minister of the interior, Leopold Lippmann as state secretary, and Carl Cohn as senator for finance in Hamburg. Support for antidemocratic and nationalist-antisemitic groups grew significantly. The main actor among them was the German Nationalist Protection and Defiance Federation Deutschvölkischer Schutz-und Trutzbund, which served as an umbrella organization uniting a large number of right-wing extremist associations and organizations.

Accusations against the Jews regarding their supposedly insufficient participation in the war led to the so-called “Jewish census” [Judenzählung] during the war in 1916, which the War Ministry carried out under pressure from right-wing extremist organizations claiming “Jewish shirking.” Despite refutations of this claim by Jews as well as others, the stereotype of “Jewish shirking” stuck in the minds of many people, particularly in the context of the “stab-in-the-back myth” [Dolchstoßlegende]. Moreover, Jews such as Hamburg shipping company owner Albert Ballin were accused of having enriched themselves during the war. Apart from books such as the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” antisemitic agitation made use of modern means of mass communication such as flyers, broadsheets, and poster stamps, of which the DVSTB distributed millions and which were often produced in Hamburg.

Parallel to this expression of organized political antisemitism, those forms of anti-Jewish attitudes and practices which had already been present in Imperial Germany not only continued to exist in the Weimar Republic, but now became more drastically apparent in daily life and manifested themselves in the exclusion of Jews from associations or in the so-called “Bäderantisemitismus” [resort antisemitism].

Sealing band of a letter, 1933

Source:

Collection Wolfgang

Haney.

Antisemitism did not merely confine itself to propaganda and offensive songs, however. Rather the early 1920s are characterized by political assassinations of prominent Jews such as Rosa Luxemburg or Walther Rathenau and by a nationwide wave of anti-Jewish riots, which spared Hamburg, however. The fact that Hamburg’s city assembly debated antisemitism as early as 1920 shows that its members considered it a serious problem at this early juncture, as did Jewish congregations, the Central Association of German Citizens of the Jewish Faith (CV) Centralverein deutscher Staatsbüger jüdischen Glaubens or the Zionist Association Zionistische Vereinigung, all of whom spoke out against antisemitic attacks. In Hamburg, too, where some assembly members had formed an Association for the Fight against Antisemitism Verein zur Abwehr des Antisemitismus, this association, in concert with the Jewish press and the Jewish community fought back by bringing charges of incitement of the people [Volksverhetzung] or by reporting signs of growing antisemitism in Germany to Hamburg’s senate.

After antisemitism had ebbed somewhat in the mid-1920s, the Great Depression, which grew into a state crisis in Hamburg as everywhere else, and the rise of National Socialism linked with it marked a turning point. In the radicalized struggle for political dominance Jews became a preferred target. After 1928 / 29 and particularly with their election successes beginning in 1930, the NSDAP continued its anti-Jewish poster propaganda, violent attacks, threats, and boycotts. At schools for higher education and universities, National Socialist students harassed Jewish students. Like other German universities, the University of Hamburg was firmly under the influence of National Socialist state doctrine in the 1930s and 1940s. Extreme right-wing parties were able to win votes in Hamburg’s 1928 city assembly election. In 1930 the NSDAP managed to win a spectacular 19.2% of votes there despite a relatively small number of local party members. Thus Hamburg’s city assembly, too, became a platform for antisemitic polemics. Jewish congregations in Hamburg and surrounding areas now also felt the growing threat as vandalism of cemeteries, street terror, and even vandalism of synagogues occurred ever more frequently. In November 1930, a “political committee” was formed in order to develop defensive strategies. In the spring of 1932, leading National Socialists announced a number of anti-Jewish measures to be implemented once they would come to power, which led some of Hamburg’s Jews to emigrate as early as 1932 and in increasing numbers in the spring of 1933.

After 1933 the dynamic process by which violent antisemitism “from below” and the plans for legal exclusion of the Jews developed by extreme right-wing masterminds radicalized each other was advanced further by the National Socialists in the form of government politics. Immediately after their rise to power, the NSDAP began the nationwide implementation of its antisemitic agenda. In Hamburg, political leaders consistently executed nationwide orders and also carried out their own anti-Jewish policies. In late March, Karl Kaufmann, the NSDAP’s head of the Hamburg district [Gauleiter], in a radio broadcast justified the call for an anti-Jewish boycott campaign on April 1st, 1933. The boycotts were flanked by increasing antisemitic public propaganda and marked the beginning of the exclusion from German society which increasingly affected ever more areas of Jewish life. In the following period, Jews were morally defamed in a deluge of more than 2,000 laws and decrees, they were excluded from social life, economically plundered, driven out of the country and physically threatened. In Hamburg, too, Jews were targeted by anti-Jewish street campaigns orchestrated by the NSDAP and the SA in 1933 / 34, which virtually escalated into “Jew hunts” in the Grindel quarter. Out of tactical considerations, however, Hamburg overall exercised restraint with regard to radical anti-Jewish measures to avoid jeopardizing its reputation as a cosmopolitan merchant city, which it relied on for its economic stability Marginalization reached a new level when the “Nuremberg Laws” were passed in 1935. The Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor [Gesetz zum Schutze des deutschen Blutes und der deutschen Ehre] prohibited Jews from marrying “Aryans“ or having sexual relations with them. This law opened the floodgates for denunciations on the basis of “racial defilement” [Rassenschande], which could have extremely dangerous consequences particularly for the Jewish partner. In Hamburg a special chamber of the district court prosecuted infractions against this law with particular severity.

The year 1938 saw a new increase in radicalization. In late October, between 15,000 and 17,000 Jews with Polish citizenship were arrested and deported to Poland in the so-called “Polenaktion.” It was the National Socialist regime’s response to the Polish government’s decision to revoke Polish citizenship from Polish citizens who had been living abroad for an extended period of time, especially Jews. Among those affected were 1,200 Jews from Hamburg, who were taken to the Polish border and then forced to cross it. A short time later, the November pogroms of 1938 caused a surge in emigration among those Jews who had thus far remained in Germany. These pogroms “ordered” by Goebbels with Hitler’s consent were mainly carried out by the SA, SS, and NSDAP members, although parts of the general population spontaneously joined the campaigns in some places. According to National Socialist documents, 91 Jews were killed nationwide, but today a much higher number of casualties is assumed (between 400 and 1,300) while about 1,500 synagogues and 7,500 Jewish businesses were destroyed.

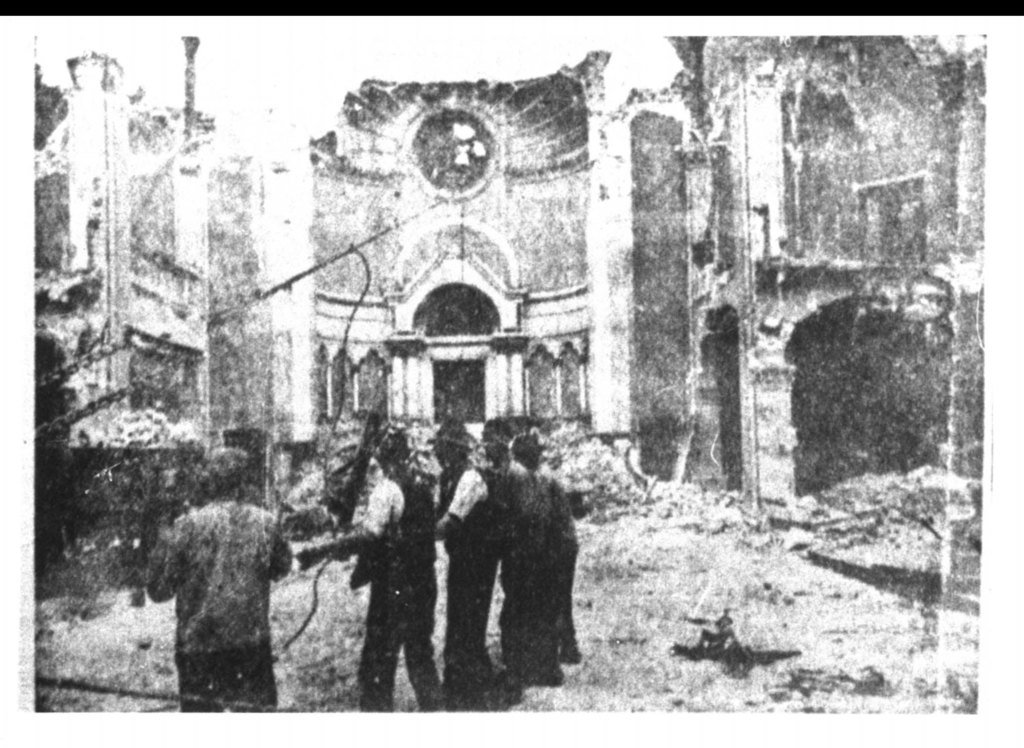

Demolition of the Bornplatz

synagogue, 1939

Source: Yad

Vashem

Photo

Archive, 971/2.

Moreover, about 30,000 Jewish men were deported to concentration camps and incarcerated for several months. In Hamburg more than a thousand Jewish men were arrested and taken from the police jail at Fuhlsbüttel to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. These campaigns and the one billion Reichsmark in “reparations” which “the Jews of German citizenship as a group” were expected to pay for the damages (done to them) were meant to be the final step in eliminating them from the economy and driving them to emigrate. The Jewish congregation in Hamburg, which counted ca. 20,000 members in the mid-1920s, had lost half of its members by 1939. Among the German population reactions to the pogroms were split. There were abettors and onlookers who approved of events, but there also are accounts of disapproval. The foreign press and foreign politicians expressed outrage at these violent excesses. The regime therefore launched a massive propaganda campaign on the radio which also used the medium of cabaret to justify events and virtually ridicule them.

Shortly after the beginning of the Second World War, the first deportations of German Jews to Poland and France were carried out. In October 1941 the final phase of the nationwide policy of persecution began: the systematic mass deportation and murder of the German Jews in the East.

Entry of Hannoverscher Bahnhof, around 1941

Source: With the kind permission of the

German Customs

Museum.

The total number of deported German Jews is estimated at 160,000 to 195,000. The first transport of 1,000 Jews from Hamburg to Lodz (then Litzmannstadt) left on October 25, 1941. Until 1945 there were 16 further transports of a total of 5,848 people. Very few Jews survived persecution within the borders of Nazi Germany. A statistic submitted to the Gestapo a few days before the end of the war by the liaison officer of Hamburg’s remaining Jewish community gives the number of 647 surviving Jews, almost all of whom were married to a non-Jewish spouse in a so-called “mixed marriage” [“Mischehe”]. Another 50 to 80 people had survived in hiding or using a false identity. The statistic structured according to National Socialist racial policy shows to what extent one’s chance of survival depended on the status one was ascribed. The total number of victims from Hamburg is estimated at about 10,000. So far the names of 8,877 of them have been verified.

Early opinion polls carried out in Germany show that after the end of the war, antisemitic attitudes, now “privatized,” continued to exist among large segments of the population; they manifested themselves in vandalism of cemeteries, graffiti, and verbal insults. On the one hand, “post-Auschwitz antisemitism” still bears all the characteristics of “classic” antisemitism. Yet the forms it took underwent a change since antisemites now had to react to the genocide either by denial, by rejecting responsibility or by projecting guilt onto the Jews or the state of Israel. These projections were often linked to earlier conspiracy theories in the wake of the publication of the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion.” While public expressions of antisemitic convictions were proscribed in the Federal Republic, they repeatedly caused antisemitic scandals in the early postwar years and into the late 1950s because the courts showed little willingness to prosecute such deliberate insults and the public openly displayed their antisemitic attitudes during court trials, for example by ovations for film director Veit Harlan, who was put on trial in Hamburg for his Nazi propaganda film “Jud Süß” but was eventually acquitted.

Veit Harlan

after the trial in Hamburg, 1949

Source: German Federal Archives,

item 183-R76220, Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY-SA

3.0.

The antisemitic scandals of the later 1950s and a wave of antisemitic graffiti in 1959 / 60 eventually prompted a change of mind in politics, education, law, and culture which in the 1960s was reinforced by the Eichmann and Auschwitz trials. This was accompanied by a decrease in antisemitic attitudes among the German population.

In the postwar years antisemitism targeting Israel did not play a significant role in West Germany. Only after the June war of 1967 did a part of the political left react with a radical anti-Zionism which sometimes had antisemitic undertones. In June 1969, Arabic and German students prevented Israeli ambassador Ben Nathan from giving a lecture at the University of Hamburg by shouting “El-Fatah” and “Ben Nathan get out,” although the majority of students opposed them by shouting “El-Fatah get out.” In the 1980s the relationship to the Jews became part of the debate in the Federal Republic about memorializing the National Socialist past, which resulted in a number of scandals and conflicts. After German unification, a new wave of xenophobic violence, neo-Nazi demonstrations, and antisemitic hate crimes occurred in the course of the debate on asylum law beginning in 1991. Meanwhile the spread of antisemitic attitudes among the population hardly changed at all. Yet antisemitism since the 1990s was not limited to the extreme right-wing fringes. In addition to antisemitism out of a rejection of responsibility, Israel’s policy towards the Palestinians has increasingly become a motif for anti-Jewish resentment since the beginning of the new millennium. This Europe-wide development has been labeled “the new antisemitism.” It is described as having found a new target in Israel and being supported not only by the extreme right, but also by the radical left and Muslim migrants.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the material is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute it in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Werner Bergmann (Thematic Focus: Antisemitism and Persecution), Prof., is Professor at the Centre for Research on Antisemitism, Technical University of Berlin. His research interests centre on the sociology and history of Antisemitism and related fields, such as racism and right-wing extremism.

Werner Bergmann, Antisemitism and Persecution (translated by Insa Kummer), in: Key Documents of German-Jewish History, 22.09.2016. <https://dx.doi.org/10.23691/jgo:article-218.en.v1> [February 24, 2026].