The diary covers the period of two years and seven months. It consists of three octavo notebooks: The first entry in notebook 1 was made between March 6 and March 11, 1943 (undated); Notebook 2 begins with a note dated November 15, 1943; Notebook 3 starts on August 1, 1945 and ends with an entry dated November 8, 1945. In addition to the entries, the notebooks also contain notes and poems that were transcribed as well. As far as possible, the transcriptions are true to the original; any changes, additions, or editorial notes are marked as such. Footnotes that already exist in the print edition are shown as (i)-buttons; newly added notes by the Institute for the History of German Jews that reflect the latest state of research are marked as endnotes. The transcribed text is also put side by side with the digital facsimile. More detailed information about the edition guidelines can be found here.

The editor is Dr.

Barbara

Müller-Wesemann; responsible for the new edition and editing of the

digital edition: Institute for the

History of German Jews, additional editors:

Dr. Sonja

Dickow-Rotter, Dr.

Anna Menny; technical

realization: Daniel Burckhardt, translation:

Dr. Erwin Fink. We would

like to thank the Hamburg State Agency for Civic

Education Landeszentrale

für Politische Bildung

Hamburg

for its financial support.

Hermann Glass. IGdJ picture database, PER00523.

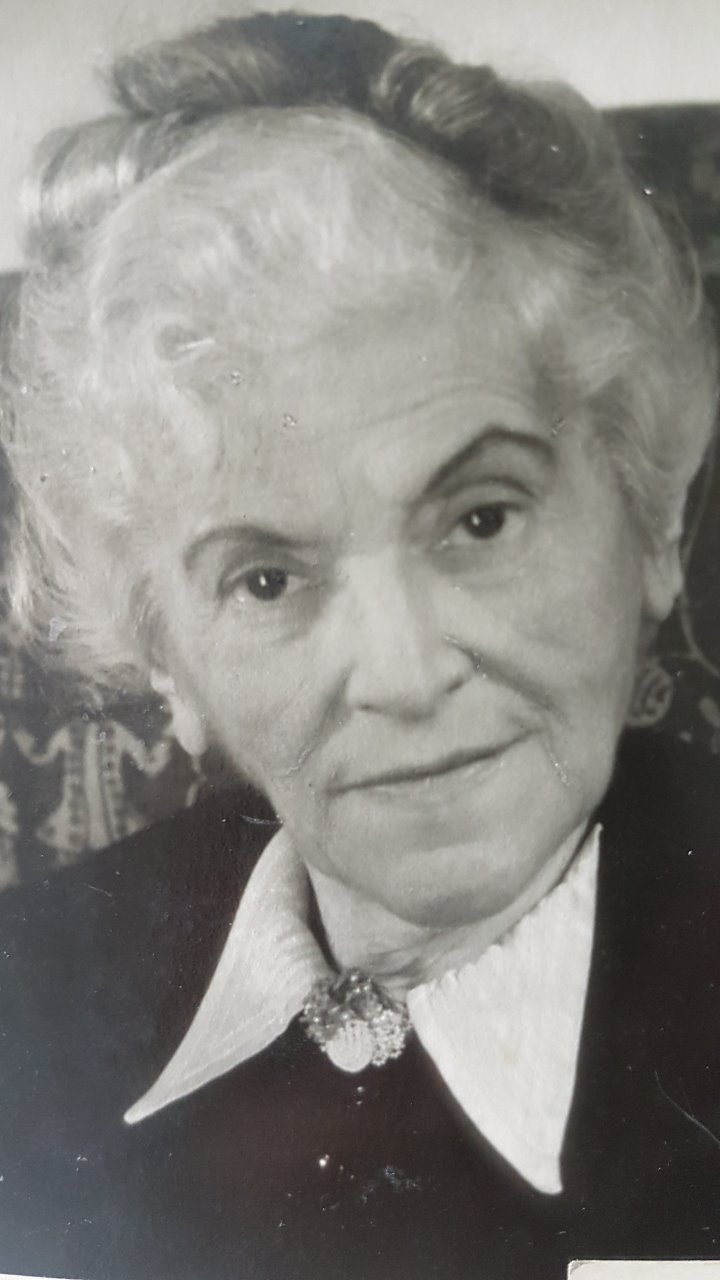

Martha Glass. IGdJ picture database, PER00525.

78 years after Martha Glass wrote the first entry in her diary and 25 years after the publication of the edition of that diary, edited by Barbara Müller-Wesemann, the examination into testimonies of National Socialist persecution in a worsening social climate, leading to an increase in xenophobia and antisemitism, has not lost its relevance. A republication of the diary edition, as an online version under the umbrella of the source edition entitled “Hamburg Key Documents on German-Jewish History” published by the Institute for the History of German Jews IGdJ and funded by the Hamburg State Agency for Civic Education [Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Hamburg], aims to increase the visibility of this important historical document. At the same time, the digital processing of the diary entries and of the commentary written by Barbara Müller-Wesemann in accordance with current scholarly standards opens up new functionalities, such as cross-linking between entries, jumping to specific historical data, the inclusion of glossary entries, and the possibility of exploring certain topics in greater depth by linking to Key Documents articles. The tagging with standard data (persons, organizations, and places) offers additional means for search queries and digital analysis tools.

Books, too, have fates of their own, a Latin proverb says, though as experience tells us, their fates are not always particularly dramatic or spectacular. Certainly sometimes we hear about exciting finds of long lost manuscripts in attics, in the corners of cellars or in the inclusions of walls; but often they are within our reach – printed or handwritten testimonies of times gone by – available as a matter of course so much so that we do not even notice them, and sometimes a special occasion is needed to play them into our hands, purely by chance. Whatever the reason, before long, we sense having something in front of us that we cannot simply put aside again.

In connection with a more extensive study on Jewish artists in Hamburg during the Nazi era, from 1989 onward, I followed up every hint that promised to bring me new insights in my search for traces concerning those actors, musicians, dancers, cabaret artists, and painters. One of them was Paul Wilhelm (Pollo) Adler, son of the Hamburg artist and university lecturer Friedrich Adler. Paul Wilhelm Adler had initially worked as a ceramicist in the Hanseatic city and had joined the Berlin Jewish Cultural Association Jüdischer Kulturbund Berlin as a musician in the late 1930s. From there, the 26-year-old was deported by the Nazis in 1941 to Theresienstadt, then to Auschwitz, and murdered. No one was able to tell me about the last stages of his life until one day I heard an eyewitness report according to which Pollo Adler had been seen in Theresienstadt. An eyewitness report? Rather, it was the entry in a diary, written in Theresienstadt. Its author, Martha Glass from Hamburg, had once been in the Adler family’s circle of friends. Like Pollo Adler, she had been deported to Theresienstadt and she had recognized the young artist at a concert of the camp orchestra. Martha Glass survived the camp; since her death in 1959, her daughter Ingeborg had kept her mother’s diary. I had visited Ingeborg Tuteur, née Glass, several times in New York as part of my research on the Hamburg Jewish Cultural Association Jüdischer Kulturbund Hamburg. At my request, she handed over the diary to the Hamburg State Archive in 1995.[I]

Three small octavo notebooks sat in front of me – much too small, it seemed to me, for the large handwriting that appeared to be energetic. There was no room for spaces, paragraphs, or margins. But where was the passage about Pollo Adler? It was not possible just to flip through the pages, so I picked up the first notebook and read, “1943 – My diary. On January 19, Hermann passed away, of severe diarrhea, cardiac insufficiency due to hunger, from which we all suffer terribly. Life in Theresienstadt goes on.”

Three plain empty notebooks – they were among the few possessions left to Martha Glass from Hamburg – can certainly not replace a loved one, but in this situation of captivity and being at the mercy of others, they were both interlocutors and confidants at the same time. Life in Theresienstadt would last another two and a half years for Martha Glass, around 30 months during which she would continue to write down her experiences and observations, her feelings and secret thoughts, and give an account of her own conduct.

The policy of the rulers involved deceiving the world about the millionfold murder and repeatedly removing the traces of the boundless barbarism; therefore, records like those of Martha Glass were life threatening to the author, and their discovery would have meant certain death for the chronicler. However, in the camp’s everyday life, dominated by misery, hunger, and fear, were they not at the same time life saving, a remedy for psychological self-abandonment and inner loneliness? Writing a diary relieves the pressure of words unspoken. Diaries tell – in a double sense – stories of survival:

“People write about their efforts to stay alive in murderous times: in the drumfire at the front, at home in the bombing hail, in the forced community of the prison camp, on the run, and in the chaos of 1945. But survival also means that the diarists – like every professional author – are driven by the same force: the passionate desire to save themselves by writing.” Mein Tagebuch. Geschichten vom Überleben 1939–1947, ed. by Heinrich Breloer, Cologne 1984, p. 7.

In contrast to memoirs, the narrating takes place in immediate temporal proximity to events experienced, not informed by the subsequent insights of the person looking back; and in contrast to an autobiography, in which the personal experiences of a certain phase of life are integrated into the horizon of a continuously presented life story and are often interpreted as triggers or evidence for later developments, in a diary the daily or irregularly recorded impressions are juxtaposed without connection. They are only able to sketch the respective moment and reflect the events as they appear to the author at the time of writing. Precisely this concentration on short periods and the lack of knowledge about the connections and consequences of events and actions make a diary unique and authentic. If Martha Glass had subsequently written an autobiography instead of a diary, the reader would have been presented with a completely different, in any case a more distanced impression of Theresienstadt. Many details of the quite “normal” daily routine would have long since been forgotten or would not have been considered worth telling from a distance. In this way, however, the reality of imprisonment in its everyday manifestations is revealed to us in the account at hand and it allows us to recognize, not least through the sometimes stereotypical repetition of “banal” details such as meal plans, contents of packages, or hygiene precautions the importance of such elementary conditions of survival as food, cleanliness, and health in times of extreme hardship.

In Theresienstadt, as in other ghettos, concentration and extermination camps, diaries were written, despite the risk they entailed; many have been preserved and can be consulted today in archives and memorials. In contrast to autobiographies and memoirs, whose number has grown into nearly immeasurable dimensions since the 1980s, diaries have been published less frequently and later. The first wave of publications of autobiographies of persecuted persons occurred immediately after the end of the war. In the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, comparatively little was published in this field. From the 1980s on, a veritable flood of publications set in.[II] Initially, this genre was neglected by researchers as well. In the meantime, some works have appeared that focus on diaries from Theresienstadt.[III] Their authors were both simple ghetto occupants and persons with central functions for the ghetto community, such as Egon Redlich.[IV] At the same time, the question of the significance of diary writing for the ghetto inhabitants also came into focus.[V] Diaries can be an important source to break open the perpetrator-centered perspective on the victims of National Socialism.[VI]

This diary is one of the few and at the same time the most comprehensive among contemporary documents written by a Hamburg resident.[VII] Although more than 20 years have passed since the first publication of Martha Glass’ diaries, they still have a unique characteristic, which underlines the importance of this historical document.

Martha Glass was born on January 31, 1878 as Martha Stern in Mönchen-Gladbach, then still München-Gladbach, and she grew up with two brothers and one sister. Her father was a merchant by profession, her mother a homemaker.

Martha Glass as a young woman. IGdJ picture database, Collection Müller-Wesemann, PER00534. With the kind permission of the family of Martha Glass.

Martha was very athletic, played tennis, went swimming, and rode a bicycle, which was not necessarily common for girls and women at the end of the 19th century. Following the girls’ secondary school (Lyceum), which she completed with the intermediate secondary school certificate [mittlere Reife], her father enabled his musical daughter to train as a singer and pianist in Düsseldorf.

In her hometown, Martha Stern met 39-year-old Hermann Glass in 1902; he came from Stanowitz near Breslau (today Stanowice near Wroclaw in Poland), but had already resided in Hamburg for several years. In 1899, he had opened a women’s clothing store on Stadthausbrücke in what was then one of the most exclusive residential and commercial buildings in downtown Hamburg, the so-called “Millionenbau.” The “Millionenbau” was built in 1889 / 90 by the architects Hallier and Fittschen and received its name because of the construction costs, unusually high up to that time. The building was destroyed in the Second World War. Today a modern building occupies the same site.

On August 9, 1903 According to Hermann Glass's 1939 income tax return (StaHH 621-1/84_20), the couple married on August 8, 1903., the couple married and settled in Hamburg. In the course of the 39 years that Martha and Hermann Glass were to spend in the Hanseatic city, they lived in the districts of Rotherbaum, Eppendorf, and Harvestehude, in other words, in those neighborhoods where a large proportion of the Jewish middle classes resided. In the early 1930s, 70 percent of the Jewish population lived in the districts of Harvestehude, Rotherbaum, Eppendorf and Eimsbüttel. Martha and Hermann Glass resided successively at Hansastrasse 74, Isestrasse 6, Beim Andreasbrunnen 5, and Abteistrasse 35. In 1904, their daughter Edith was born, and in 1912 their second daughter, Ingeborg.

Martha with Edith as baby. IGdJ picture database, Collection Müller-Wesemann, PER00535. With the kind permission of the family of Martha Glass.

Martha’s daughters Edith and Inge. IGdJ picture database, Collection Müller-Wesemann, PER00536. With the kind permission of the family of Martha Glass.

Martha and her daughter Edith in the boat. IGdJ picture database, Collection Müller-Wesemann, PER00537. With the kind permission of the family of Martha Glass.

Edith with her father Hermann Glass on the beach. IGdJ picture database, Collection Müller-Wesemann, PER00538. With the kind permission of the family of Martha Glass.

Martha, Hermann (?) and daughter Edith on the beach. IGdJ picture database, Collection Müller-Wesemann, PER00539. With the kind permission of the family of Martha Glass.

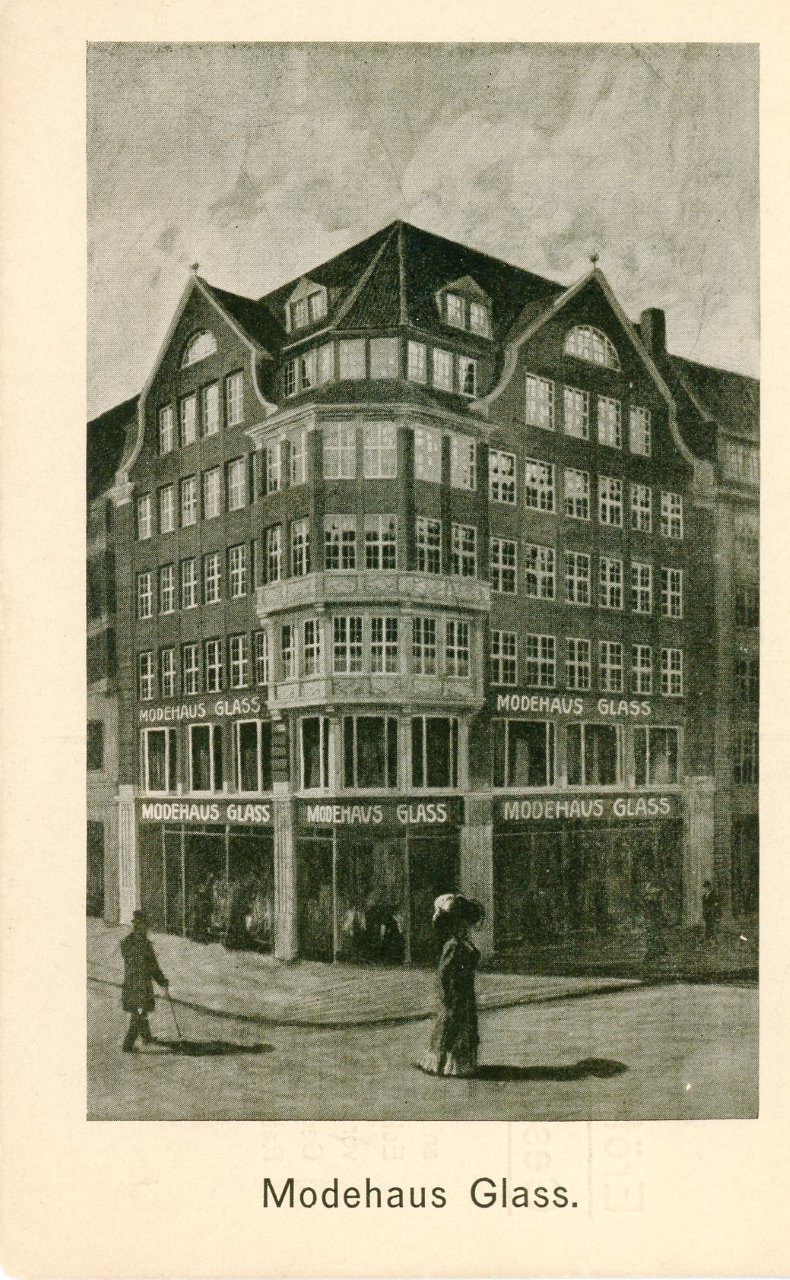

One year earlier, Hermann Glass had opened a fashion store on Mönckebergstrasse / corner of Bergstrasse. He was both builder and owner of the entire building; Fritz Höger, the future constructor of Chilehaus, was its architect. The house was given the name of its builder, and the name “Haus Glass” was embedded in the sidewalk as a mosaic. The mosaic survived Nazism and the war unscathed and could be seen into the 1950s when Martha Glass visited Hamburg again. Cf. Reisetagebuch von Martha Glass, IGdJ archive, 14-039. The fashion business went bankrupt as early as 1912 and Hermann Glass became a house, farm, and estate broker.

Glass fashion store, Mönckebergstrasse/Bergstrasse. IGdJ picture database, Collection Müller-Wesemann, BAU 00380A+B.

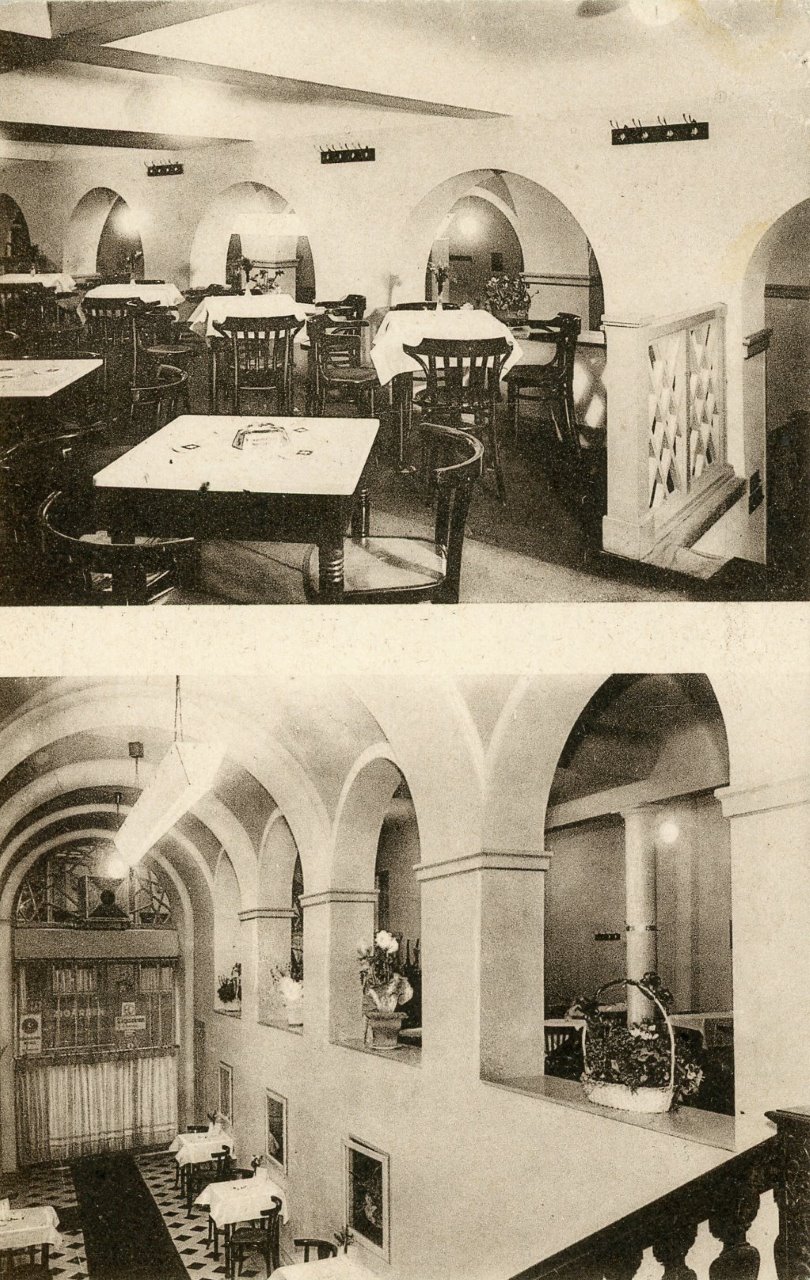

He acquired real estate and let the properties out on lease, including the restaurant “Reichskanzler” on Colonnaden / corner of Grosse Theaterstrasse. In the 1920s, he also managed a commercial agency; his office was still located in his house on Mönckebergstrasse. Hermann and Martha Glass were staunch democrats; Hermann voted Social Democratic, Martha voted left-liberal German Democratic Party [Deutsche Demokratische Partei – DDP].

Postcard of the restaurant “Reichskanzler”. IGdJ picture database, Collection Müller-Wesemann, BAU00381.

The couple had an extensive circle of friends and acquaintances; among them were the Robinsohn and Hirschfeld families In the course of the “Aryanisation” of Jewish companies, the Hirschfeld brothers were forced t give up their fashion house on Neuer Wall at the end of 1938. The house was taken over by the Franz Fahning Company. At the beginning of 1939, the Robinsohn brothers also had to “sell” their store on Poststrasse / Neuer Wall. For a comprehensive study on “Aryanisation” in Hamburg, see Frank Bajohr, “Aryanisation” in Hamburg: The Economic Exclusion of Jews and the Confiscation of Their Property in Nazi Germany, trans. George Wilkes, New York 2002. – both owned large clothing stores in downtown Hamburg –, the Karlsberg family (general agent of the British Cunard Line for Germany); the Hamburg representative of the Berlin Ullstein publishing house, Felix Wolff, and his wife Martha; Max Samson and his wife Rose; the Leon Ekert family (import of sports equipment); the dentist Dr. Max Brandenstein and his wife; Arthur and Hedwig Martienssen; as well as Johannes and Jenny Kahn. Hermann Glass was a passionate skat player, Martha played bridge. Since she was suffering from bilious disease, she regularly went to the spa, including to Karlsbad (today Karlovy Vary in the Czech Republic).

Family Glass with other (not known by name) persons. IGdJ picture database, Collection Müller-Wesemann, PER00540. With the kind permission of the family of Martha Glass.

The Glass couple at the breakfast table, Hamburg March 1933. IGdJ picture database, Collection Müller-Wesemann, PER00530.

In the bourgeois circles of the time, a career as an artist, combined with public appearances, was considered unsuitable for a woman, so it went without saying that Martha Glass had abstained from practicing her profession. Nevertheless, she always remained an artist at heart; her remark, “The only thing that interests me is music” was always remembered by her children. The Musikhaus Steinway engaged her as a pianist for a time and had her demonstrate Steinway grand pianos for potential buyers in her private music salon. Apart from that, she sang and played only in the circle of family or friends and belonged with her two daughters to the temple choir of the Liberal Israelite Temple Association Tempelverband. The Temple Association was one of three religious associations representing the religious interests of Jewish residents of Hamburg. In 1931, the new temple on Oberstrasse was dedicated (today Rolf-Liebermann-Studio of the NDR broadcasting corporation). The temple choir with a rich tradition was in the service of the Liberal Temple Association and was directed by Georg de Haas since 1925. She was a member of the Singakademie, an “association of friends of the art of music for the purpose of study and performance of serious, particularly religious, singing,” This is the official name. which gave public concerts in the Musikhalle and the Michel (church) on the Day of Repentance, in the winter, and during Easter week, being accompanied by the Philharmonic Orchestra; at the end of the 1920s, the choir was directed by the renowned conductor Eugen Papst. Martha Glass had a season ticket to the opera and in addition, she also attended the other theaters in the Hanseatic city. Her favorite composers were Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler, her favorite opera was Bizet’s Carmen. Martha’s vocal range was mezzo-soprano. Thus, it makes sense that she would have identified herself very much with the role of Carmen.

Edith and Inge Glass. IGdJ picture database, Collection Müller-Wesemann, PER00543. With the kind permission of the family of Martha Glass.

Edith Glass 1922. IGdJ picture database, Collection Müller-Wesemann, PER00544. With the kind permission of the family of Martha Glass.

Edith’s wedding. IGdJ picture database, Collection Müller-Wesemann, PER00545. With the kind permission of the family of Martha Glass.

Martha and her granddaughter. IGdJ picture database, Collection Müller-Wesemann, PER00546. With the kind permission of the family of Martha Glass.

The ordeal of the Jewish population began many years before the large-scale deportations to the concentration and extermination camps in 1941, for the Nazi state was established along with prevailing racist propaganda and organized terror. This reached its first peak on April 1, 1933: The population was called upon to boycott Jewish stores, doctors’ practices, and law firms; SA Sturmabteilung troopers stood guard at the entrances, and countless shop windows were smeared. On May 10, student associations issued the slogan “Against the un-German spirit” and burned the works of Jewish and leftist authors in bonfires. In Hamburg, the book burnings took place on May 15 and 30, 1933. The Hitler Youth and the German National Association of Commercial Employees [Deutsch-Nationaler Handlungsgehilfenverband] also took part in the book burning in late May. Cf. the catalog of the exhibition “Where one burns books…‘ Burned books, banned and murdered authors of Hamburg” [“Wo man Bücher verbrennt...” Verbrannte Bücher, verbannte und ermordete Autoren Hamburgs], shown in the Hamburg State and University Library in 2013 and curated by Wilfried Weinke. The state passed a flood of racist laws. With the "Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service” [“Gesetz zur Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums”] dated April 7, 1933, all Jewish civil servants were dismissed from the civil service, from schools, universities, administration, courts, theaters, orchestras, clubs, and professional associations. On September 15, 1935, at their Reich Party Congress in Nürnberg, the National Socialists passed two laws that legalized the discrimination and exclusion of German Jews from society. The first was the “Reich Citizenship Law” [“Reichsbürgergesetz”] which deprived Jews of their political rights, i.e., their equality before the law, and the second was the “Law for the Protection of German Blood and Honor” [“Gesetz zum Schutze des deutschen Blutes und der deutschen Ehre”], which prohibited marriages or extramarital relations between Jews and non-Jews. Any violations of this law were severely punished as so-called “racial defilement” [“Rassenschande”].

Many smaller Jewish business owners were forced to close their companies or sell them to non-Jews. In general, Jewish entrepreneurs were closely monitored by the authorities, and the slightest infraction of the regulations resulted in severe penalties. Those who wanted to emigrate had to leave behind a quarter of their assets by way of a “Reich flight tax” [“Reichsfluchtsteuer”]. In April 1938, all Jews had to disclose any assets exceeding 5,000 RM[VIII], including household effects, jewelry, and insurance policies. Any lease or sale of Jewish property required official approval. Jewish artists employed in municipal and private theaters and orchestras were, with very few exceptions, dismissed in the first years after the transfer of power to Hitler. Those among them who wanted to hold on to their professions had only the choice of emigrating or becoming actively involved in the Jewish Cultural Association Jüdischer Kulturbund. After 1933, the Cultural Association was the only forum that offered an extensive artistic program with theater, concerts, expressive dance, cabaret, lectures, and art exhibitions to an exclusively Jewish audience in over 80 German cities under the strict control of the Nazi authorities. In Hamburg, it was opened in 1934. Felix Wolff was one of its board members. Ingeborg Glass, who had been forced to discontinue her studies of Romance languages, theater, and newspaper studies in Munich because of her Jewish background, became involved in the Hamburg Cultural Association as a secretary and “script girl.” Hermann and Martha Glass had also joined the Cultural Association and attended its events. Among their friends were the conductor and head of the Frankfurt Cultural Association FrankfurterKulturbund Orchestra, Hans-Wilhelm Steinberg, and the popular cabaret artist of the Berlin Cultural Association, Max Ehrlich. When these two artists performed on the Cultural Association Kulturbund stage in Hamburg, they stayed with the Glasses. The Artists’ and Spectators’ Association , whose existence was constantly threatened not only politically but also economically, depended on both financial support and donations in kind. Among other things, Martha Glass provided items from her household, furniture or tableware, to serve as props for the theater performances. On the Hamburg Cultural Association Hamburger Kulturbund, see Barbara Müller-Wesemann, Theater als geistiger Widerstand. Der Jüdische Kulturbund in Hamburg 1934–1941, Stuttgart 1996.

Ingeborg Glass circa 1937. IGdJ picture database, Collection Müller-Wesemann, PER00524.

Martha and Hermann Glass probably during a vacation in Italy, taken on November 14, 1937. IGdJ picture database, Collection Müller-Wesemann, PER00531.

Martha Glass at Capri, June 1938. IGdJ picture database, Collection Müller-Wesemann, PER00529.

In late fall of 1938, life in Germany was made increasingly difficult for Jews. On October 28, 1938, all Polish Jews living in Germany were expelled across the Polish border, including the parents and siblings of Herschel Grynszpan from Hannover. The young Grynszpan himself resided in Paris; when he learned of the deportation of his parents, he shot the German embassy staff member Ernst vom Rath and with this act provided the pretext for the pogroms of November 9-10, 1938. SA Sturmabteilung and SS Schutzstaffel paramilitary units desecrated about 400 synagogues and destroyed some 7,500 Jewish stores; almost 100 people were murdered, and about 30,000 Jewish men were deported to concentration camps. The November pogroms were followed by numerous anti-Jewish measures. The Jewish population had to pay for all the damage; as “atonement” for the murder of vom Rath, payment of 1 billion Reichsmark was demanded, and each Jewish citizen had to contribute 25 percent of personal assets. In addition, insurance payments due, amounting to 225 million RM, were withheld by the state, and finally the Jews had to “restore the streetscape.” On the so-called Polenaktion (expulsion of Polish Jews) in 1938, see, among others, Trude Maurer, “Abschiebung und Attentat. Die Ausweisung der polnischen Juden und der Vorwand für die ‘Kristallnacht‘,“ in: Walter H. Pehle (eds.), Der Judenpogrom 1938: Von der Reichkristallnacht zum Völkermord, Frankfurt a. M. 1988, pp. 52–73; Beate Meyer, „Das Schicksalsjahr 1938 und die Folgen,“ in: Beate Meyer (ed.), Die Verfolgung und Ermordung der Hamburger Juden 1933–1945, Hamburg 2006, pp. 25–32; and Sybil Milton, „The Expulsion of Polish Jews from Germany. October 1938 to July 1939,” in: Leo Baeck Institute Year Book 29 (1984) 1, pp. 169–174. Among the extensive research on the November pogroms of 1938, works to mention include Wolfgang Benz, Gewalt im November 1938. Die Reichskristallnacht. Initial zum Holocaust, Bonn 2018; Raphael Gross, November 1938. Die Katastrophe vor der Katastrophe, Munich 2013; Harald Schmid, “Erinnern an den ‘Tag der Schuld.‘ Das Novemberpogrom von 1938 in der deutschen Geschichtspolitik,” in Forum Zeitgeschichte 11, Hamburg 2001, as well as the catalog for the exhibition entitled “Kristallnacht” Antijüdischer Terror 1938. Ereignisse und Erinnerung, published by the Stiftung Denkmal für die Ermordeten Juden Europas and the Stiftung Topographie des Terrors in 2018.

By the beginning of the war in September 1939, the Jews had been expelled from all branches of the German economy and thus robbed of practically every means of professional livelihood. All Jewish businesses and retail stores were closed or “forcibly Aryanized”; no Jew was allowed to dispose freely of personal assets from then on. Jewish publishing houses, bookstores, and associations were liquidated. As early as 1933, Hermann Glass, like all Jewish brokers, had been excluded from the Reich Association of German Brokers Reichsbund deutscher Makler, but he still held his license as a mortgage broker until 1938. From that point on, he was no longer allowed to use a professional title behind his name.

Martha and Hermann Glass with their daughter Edith on the Elbe, Easter 1939. With the kind permission of the family of Martha Glass.

In August 1939, the commercial building on Mönckebergstrasse / corner of Bergstrasse was sold under compulsion to a Hamburg merchant in the course of “Aryanization.” The sale price was transferred by the new owner to a “security account” “Sicherungskonto”, which Hermann Glass could dispose of only with approval by the Chief Finance Administrator Oberfinanzpräsident, i.e., not at all. At this time, Hermann Glass rented an office in the building on Mönckebergstrasse and carried out the administrative tasks left to him. In June, he had to sell another house on Steindamm / Kleiner Pulverteich.[IX] He owned 50 percent of that building; in late June 1941, he was forced to give up his office.

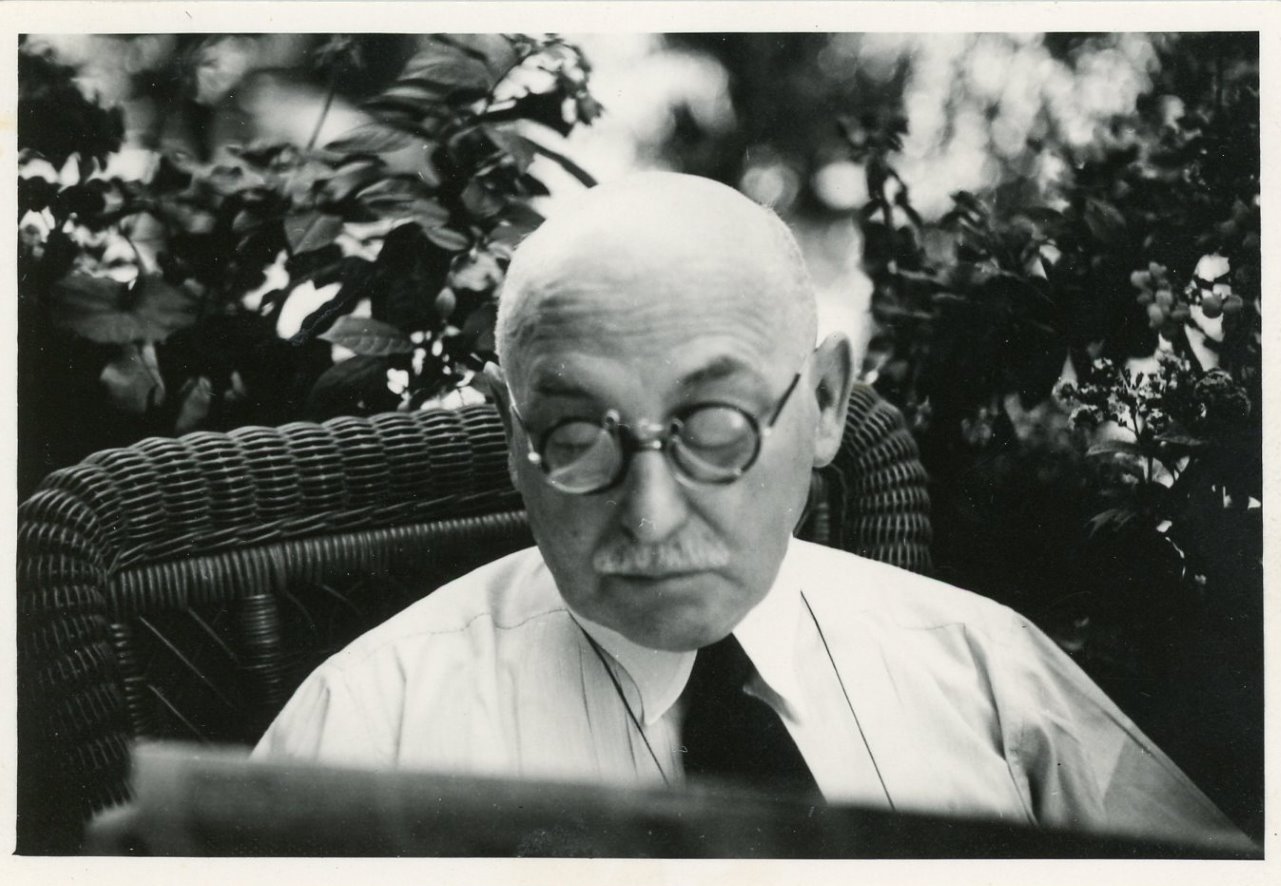

Hermann Glass reading, 1939. IGdJ picture database, Collection Müller-Wesemann, PER00533.

Residence of the Glass family, Abteistrasse 35. IGdJ picture database, Collection Müller-Wesemann, BAU00379.

Hermann and Martha Glass lived a very secluded life and spent most of their time in their house on Abteistrasse. Their oldest daughter Edith had remarried after the death of her first husband Rudolph Eichholz and resided in Berlin with her non-Jewish husband Reinhard Benecke and her daughter from her first marriage. The younger daughter Inge had emigrated to Italy in 1938 and met her future husband, Edgar Tuteur. Martha had visited her daughter Inge in Naples in 1938. The German Jews actually no longer possessed passports at that time, but the Nazis had overlooked Martha Glass when confiscating the passports. In the meantime, her circle of friends and acquaintances had also become much smaller due to emigration. While about 10 percent of the Jewish population had emigrated in each of the years up to 1937, by 1938 that proportion had risen to 24 percent. Ina Lorenz / Jörg Berkemann, Die Hamburger Juden im NS-Staat 1933 bis 1938/39, vol. 2 monograph, Hamburger Beiträge zur Geschichte der deutschen Juden XLV, Göttingen 2016, p. 1019. Ina Lorenz and Jörg Berkemann also point out the difficulties of accurately estimating emigration figures in the early years of Nazi rule, since emigration often took place rushed and without official deregistration, and at the same time, in the early years there was a considerable return migration movement. Following the pogroms of November 1938, a mass exodus began, which was fully intended by the Nazis. Cf. Chapter XI Auswanderung aus Hamburg, in: Lorenz / Berkemann, Die Hamburger Juden im NS-Staat 1933 bis 1938/39, vol. 2 monograph. After an 8 p.m. curfew had been imposed on Jews in September 1939, the isolation of those affected became ever greater. No one dared to speak openly about the terror, and so the father described the situation in a letter to his daughter Inge with the following words, “Incidentally, mother and I are always in the house because of the 8 o’clock store closing time.” Letter to Inge Tuteur dated May 8, 1940, IGdJ archive, call number 14-039.

Countless sanctions were directed against the Jews still living in Germany, including in the private sphere, with the aim of total humiliation, plunder, deprivation of rights, and isolation.

At the end of 1940, there were 7,985 Jews living in Hamburg, of whom 2,010 were Jews aged 0 to 40; 2,812 Jews aged 40 to 60; and 3,163 Jews older than 60. At the end of 1942, 1,805 Jews were still counted in Hamburg; that was 8 percent of the Jews who had lived in the Hanseatic city in 1925. For a comprehensive overview of demographic developments during the Nazi era, see Ina Lorenz / Jörg Berkemann, Die Hamburger Juden im NS-Staat 1933 bis 1938/39, vol. 1 monograph, Hamburger Beiträge zur Geschichte der deutschen Juden XLV, Göttingen 2016, for the year 1940, see pp. 96 and 124. Hermann and Martha Glass belonged to the large group of Jews over 60. The question why they had not left Germany can hardly be answered conclusively.[X] The reason for their staying may have been, on the one hand, that they, like so many people of their generation, had initially taken a wait-and-see attitude toward political developments in the early years of the Hitler regime; most had been of the opinion that “this ghastly business” would soon be over. In the later years, they found it difficult to summon up the strength and courage to build a new livelihood abroad without money. Those who emigrated not only had to pay the so-called “Reich flight tax” [“Reichsfluchtsteuer”], but they were also not allowed to take securities or large sums of cash with them. Moreover, people were far less familiar with the conditions in other countries and continents than they are today, and the step into emigration required great effort. No one foresaw the extermination of the Jews, the Shoah, and everyone hoped somehow to make it through the terror regime. Nevertheless, Hermann Glass seems to have applied for emigration for himself and his wife, which the authorities refused to approve. However, the conditions under which emigration could have succeeded were made increasingly difficult and ultimately impossible by the Nazi regime. In a letter to his daughter Inge on May 13, 1941, he wrote,

“Mother is not an emigration person; she does not like to give up things. I myself, dear Inge, can get used to anything, but I must be able to work, because that has been my lifeblood since my thirteenth year. But today my strength is faltering. Our migration has been registered for almost 1 ½ years, the gods know whether it will ever materialize. To find accommodation in a monastery, beyond good and evil, as Hugo von Hofmannsthal (Jewish) did in his day, that would be my cup of tea and my wish.” This is probably a misunderstanding: the Austrian poetHugo von Hofmannsthal never entered a monastery. In 1908, he came to the monastery of St. Luke as a visitor on a trip to Greece. Following this trip, he wrote about it a shepherds’ and monastery idyll, which seems like the description of a paradise. It was published with two other prose pieces in Moments in Greece [Augenblicke in Griechenland].

On October 23, 1941, Jews were banned from emigrating from Germany; two days later, the deportations began. As early as late July 1941, Reichsmarschall Göring had commissioned the head of the Security Police and the Security Service Sicherheitsdienst - SD, Reinhard Heydrich, to present an overall plan for the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question.” The Reich Security Main Office Reichssicherheitshauptamt – RSHA with the SD Sicherheitsdienst of the SS Schutzstaffel and the Security Police had existed since September 1939. Heydrich had been “Deputy Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia” since 1941; in June 1942, he was shot dead in Prague by a Czech emigrant. His successor was Ernst Kaltenbrunner; ranked above him was the head of the SS Schutzstaffel, Heinrich Himmler, the chief of the German police. Amt IV was the Gestapo Geheime Staatspolizei, and head of Amt IV B 4 was Adolf Eichmann. At the Wannsee Conference in Berlin on January 20, 1942 (attended by the SS Schutzstaffel, representatives of the Ministry of Justice and the Interior and the Foreign Office), the extermination of the Jews, which had already begun, was coordinated among Nazi agencies. Around 11 million European Jews were to be deported to the German-occupied territories in the East. Jews over the age of 65, frail Jewish persons aged 55 and older, and Jewish spouses from “mixed marriages” no longer existing were to be sent to Theresienstadt, the so-called “Altersghetto” [“ghetto for the elderly”]. On the instructions of the Reich Security Main Office, those to be deported had to sign a so-called “Heimeinkaufsvertrag” [“home purchase agreement”] in which they undertook to surrender all of their movable assets in return for their “transfer of residence” to Theresienstadt, as well as for food and medical care. The deportation of German Jews to Theresienstadt began in June 1942. A total of 17 deportations were carried out from Hamburg, eleven of them to Theresienstadt. The first deportations, beginning in October 1941, went to Litzmannstadt [Lodz ], Minsk, and Riga. About 6,000 Jews overall were deported from Hamburg. Of particular note are 8,877 Jewish residents of Hamburg who were murdered by the Nazis or died by suicide. The actual number of victims is estimated at about 10,000; see the Memorial Book entitled Hamburger jüdische Opfer des Nationalsozialismus. Edited by Jürgen Sielemann in collaboration with Paul Flamme. Veröffentlichungen aus dem Staatsarchiv der Freien und Hansestadt Hamburg. Hamburg 1995; Tobias Brinkmann, Migration (translated by Insa Kummer), in: Key Documents of German-Jewish History, 22.09.2016. [November 27, 2020]

In order to put together the transports from Hamburg, the head of the Jewish Affairs Department in the Gestapo Geheime Staatspolizei Headquarters, Claus Göttsche, demanded the surrender of the tax card file of the Jewish congregation, to which all Hamburg Jews belonged as compulsory members. The order for the “Wohnsitzverlegung” [“relocation of residence”] came by registered mail; the sender was the Gestapo Geheime Staatspolizei. The home was to be left clean and tidy, and the key had to be handed in at the police station in charge. At the appointed time, those affected had to report to a “collection point.” The collection points were the former provincial Masonic lodge Provinzialloge at Moorweidenstrasse 36, the elementary school at Schanzenstrasse 120, the Talmud Tora School at Grindelhof 30, the Congregation Center on Beneckestrasse, and the Jewish Community Center at Hartungstrasse 9/11.

Only the most essential clothing and bedding as well as food for three days were allowed to be taken along. The total weight of luggage was not to exceed 50 kilograms (approx. 110 lbs).

Upon arrival at the collection point, a list of assets had to be presented and all of the belongings were checked. Members of the Gestapo Geheime Staatspolizei confiscated jewelry and securities that were in the luggage contrary to regulations, and no later than upon arrival at the camp, the SS Schutzstaffel and guard personnel seized from the deportees the officially permitted 100 RM in pocket money. At the collection point, helpers of the Jewish congregation distributed warm clothing and food that had been prepared in the public soup kitchen of the Congregation Center on Hartungstrasse, today accommodating the Kammerspiele. In the early morning hours of the following day, the people were driven on trucks to the Hannoversche Bahnhof train station The Hannoversche Bahnhof train station was located behind the main train station; it was destroyed in the war.[XI] and from there taken by train to the east. Family members who were not on the list could come along voluntarily.

On November 24, 1941, the Gestapo Geheime Staatspolizei in Hamburg is said to have assured Hermann Glass that “in view of his age,” he did not have to expect “evacuation.” This is evident from a letter from the son-in-law dated November 30, 1941. StaHH, 314-15 Oberfinanzpräsident (Devisenstelle und Vermögensverwertungsstelle) 1938 R/3149. At that time, Hermann Glass was 78 years old, his wife Martha 63 years old. Barely eight months later, the couple received orders to report to the collection point on July 18, 1942, for the purpose of “relocation of residence.” One day later, on July 19, they and about 800 other Hamburg Jews were deported to Theresienstadt, where they arrived the following day. The first transport from Hamburg to Theresienstadt had taken place four days earlier, on July 15, 1942. In the process, 925 people were deported. The house on Abteistrasse was sealed off; residential property and assets were confiscated by the Chief Finance Administrator “to the benefit of the German Reich” in accordance with the decree of the Reich Governor. StaHH, 314-15 Oberfinanzpräsident (Devisenstelle und Vermögensverwertungsstelle) 1938 R/3149.

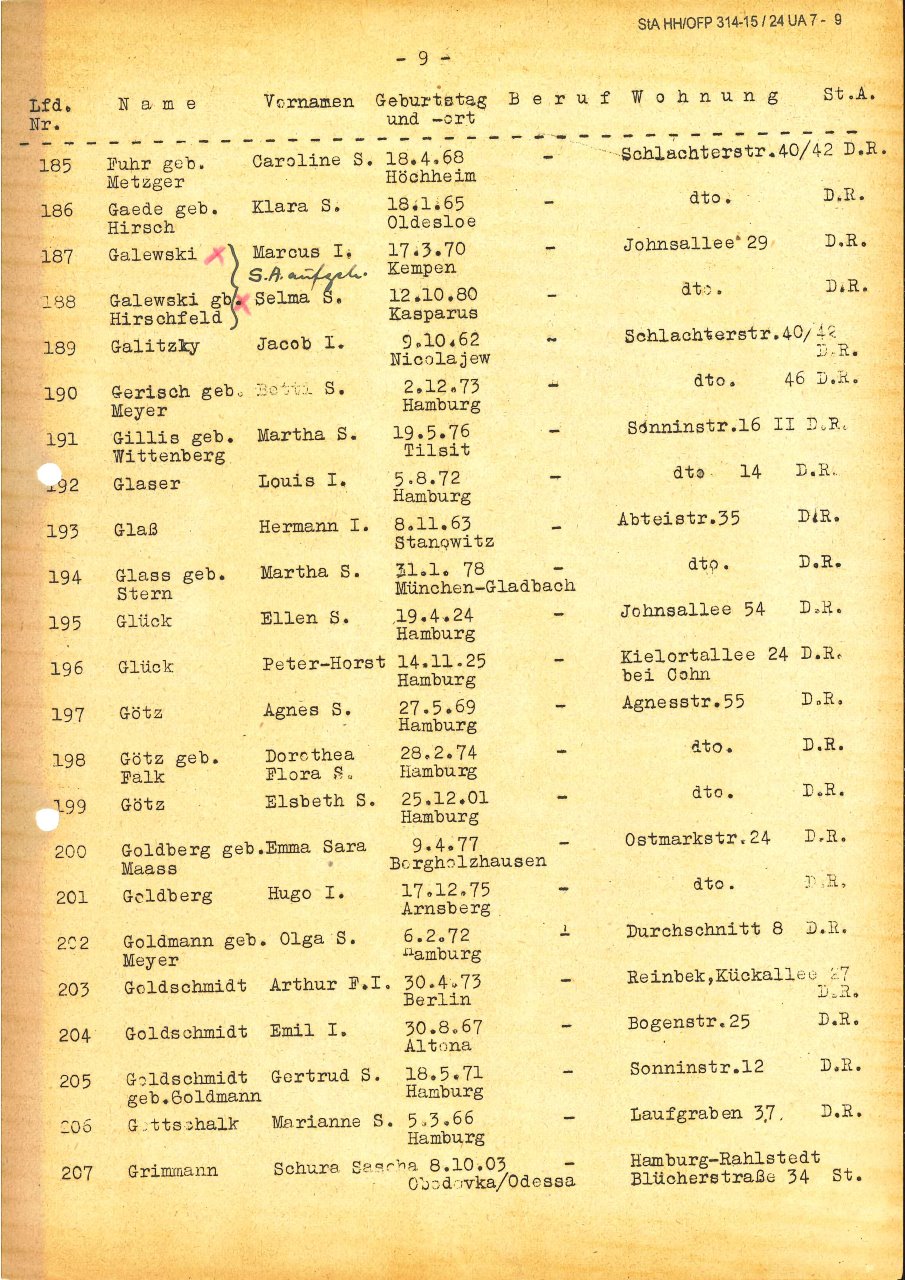

Excerpt from the list of names from the deportation to

Theresienstadt

on July 19, 1942. StaHH,

314-15, Oberfinanzpräsident, Nr. 24 UA 7. (D.R. =

German Reich

[Deutsches Reich])

Explanations to the Theresienstadt camp map[XII]

Map of the Theresienstadt camp. IGdJ archive , estate Felix Epstein, 45-054-0.

Terezin was built in the second half of the 18th century by the Austrian Emperor Joseph II as a military town. It is located about 60 kilometers (approx. 37 miles) north of Prague, near the confluence of the Eger (Ohire) and Elbe rivers. Joseph II chose the name in honor of his mother, Empress Maria Theresa. Theresienstadt was a star-shaped fortress featuring ramparts 8 to 12 meters high and six gates. Outside were the Sokolovna Clubhouse and gymnasium of the Czech gymnastics club. The building was first used in the camp as a hospital, then as a community center and theater hall. , the military hospital, the water tower, some civilian houses, and the so-called “Small Fortress,” the prison. Grass and trees grew on the inner ramparts. The two-story barracks from the 18th century were equipped with arcades and courtyards. In the center, there was a large rectangular town square (110 meters by 70 meters), which had been created especially for military parades. In addition to other military buildings, there were workshops, warehouses and an officers’ mess, as well as private houses more than 100 years old, which were primitively built and equipped with completely inadequate sanitary facilities. The unpaved streets whirled up huge clouds of dust when it was dry and windy, and when it rained they were inundated with mud. Before the camp was built, about 7,000 people had lived there, half of them civilians and half of them military.

In March 1939, the Czech territories occupied by the Germans were annexed to the German Reich as the “Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia”; at the turn of 1941/42, the garrison was withdrawn from Theresienstadt. “The civilian population of the town, about 3,700 residents, was completely resettled in July 1942,” to make way for the planned camp.[XIV] Theresienstadt, a forced labor camp of the SS Schutzstaffel, served as a transit station for the deportation of prisoners to the extermination camps in Eastern Europe. Initially established in the fall of 1941 as a collection point for Bohemian and Moravian Jews, it was declared a “Altersghetto” [“ghetto for the elderly”] for Jews from the “Old Reich” This referred to Germany without the occupied territories. in 1942. From November 24, 1941 to April 20, 1945, 141,000 people overall were deported to Theresienstadt. “The population peaked in September 1942 at 53,004 people.[XV] 15,000 concentration camp prisoners were added by evacuation transports shortly before the end of the war.[XVI] With over 75,000 prisoners, the Czechs from the “Protectorate” made up the largest group, followed by 42,345 Germans. The camp also included 15,324 Austrians, almost 4,897 Dutch, and 466 Danes. There were also 1,270 persons from Poland and 1,074 from Hungary.[XVII] The average age of the men was 44.7 years, that of the women 50.1 years. About 31,000 of the German prisoners were older than 61 years, and just under 6,000 were between 46 and 60 years old. Status as of October 1, 1944. Cf. Adler, Theresienstadt, p. 44. The majority of the prisoners came from the middle classes. In December 1942, 3,500 children under the age of 15 were registered; in December 1944 only 815. According to Wolfgang Benz, a total of about 15,000 children were staying there temporarily.[XVIII] Despite a strict ban, some 230 children were born in Theresienstadt. As a rule, mother and child were deported immediately after birth to an extermination camp.

The prisoners spoke different languages, had their national customs, and they were of different faiths; they included Catholics, Protestants, and people who adhered to orthodox, conservative, or liberal Judaism or who did not belong to any religion at all. The official camp language was German.

The camp was headed by the camp commandant as a representative of the SS Schutzstaffel, successively by Dr. Siegfried Seidel, by Anton Burger since July 1943, and by Karl Rahm since February 1944. The camp was set up with the help of Jewish experts from the fields of administration, business, technology, medicine, the crafts, as well as construction workers and support staff. From the very beginning, the plan was that a Jewish “ghetto administration” provided by the prisoners would take over the organization of camp life. There was both a “Jewish Elder” and a “Ältestenrat” [“Council of Elders,”] the latter being appointed by the “Jewish Elder” and composed of up to 27 members.[XIX] The first “Judenälteste” [“Jewish Elder”] was Dr. Jakob Edelstein from Prague. In January 1943, Dr. Paul Eppstein from Berlin took over this post, and Jakob Edelstein became his First Deputy. In September 1944, Dr. Benjamin Murmelstein from Vienna replaced Eppstein.

The administration comprised five main departments:

In addition, a labor center, youth welfare, leisure activities, security administration, the central registry, A kind of residents’ registration office that constantly monitored the number and status of the prisoners. and a bank were established. Each of these departments was divided into hundreds of subdivisions, creating an administrative apparatus that was bloated to gigantic dimensions. Even “leisure activities” had ten main departments, each with up to six subdivisions. The so-called “central provisions,” a subdivision of the Economic Department, in turn had more than 40 subdivisions, which seems absurd, particularly considering that the people in the camp received hardly anything to eat and perished on a massive scale from hunger and exhaustion. Martha Glass weighed not even 43 kilograms (just over 94 lbs) when she was given a 14-day extra convalescent diet (“Reco”). Cf. diary entry of February 13, 1944.

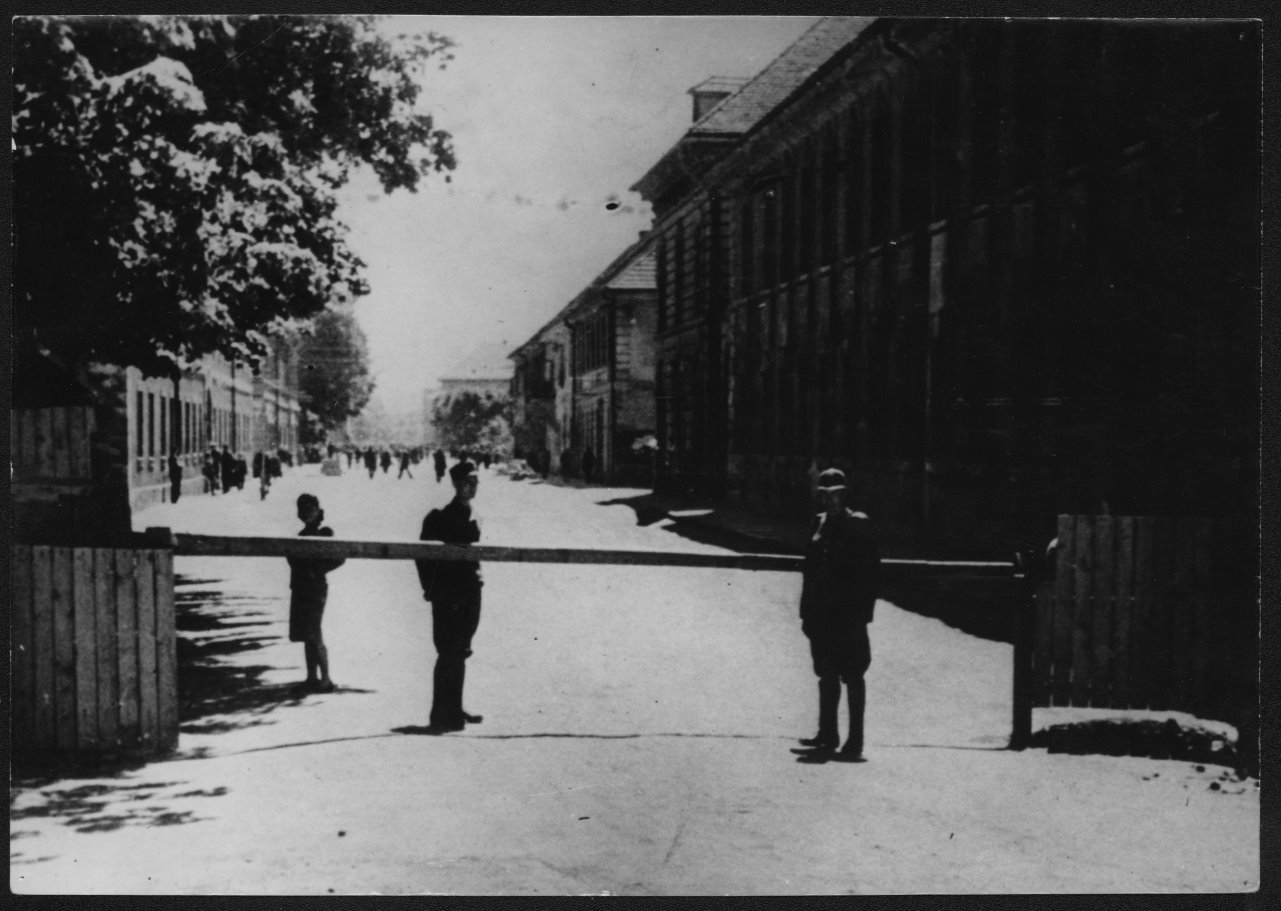

Entrance of the Theresienstadt camp, Ghetto Barrier, Photo: Karel Sallaba; Památnik Terezin: A 804.

Together with the head of the Economic Department, the Jewish Elder had to report to the SS Schutzstaffel daily. He had to draw up a file memorandum of every visit and submit a report every month. The seat of self-administration was the “Magdeburg Barracks”; insiders called it “Das Schloss” [“The Castle”], in allusion to Franz Kafka’s 1926 novel fragment of the same name, because behind its walls an anonymous power decided the life and death of the people at its mercy. In the Magdeburg Barracks, the lists for further deportation to the extermination camps were also compiled. See Viktor Ullmann, 26 Kritiken über musikalische Veranstaltungen in Theresienstadt. With a foreword by Thomas Mandl. Edited and commented by Ingo Schulz, Hamburg 1993, p. 11.

“In every camp,” writes Hans Günther Adler, “things were delusional, but in Theresienstadt to the highest degree.” Adler, Theresienstadt, p. 666. What distinguished Theresienstadt from other camps, he went on, was the great “approximation to civil norms.” This approximation had been implemented by the prisoners on the orders of the SS Schutzstaffel beyond the level required, without anyone wanting to admit that the supposed freedom of the self-administration was merely a sham freedom. Adler, Theresienstadt, pp. 629f. However, according to Adler, the “autonomy” of the Jews had in reality meant “administrative enslavement ahead of annihilation,” in which the Jewish representatives of the administration were nothing more than the “tools of the rulers,” contributing as mere stooges their part to deceiving the world about the actual events in the camp and thus to the annihilation of their own people. Adler, Theresienstadt, p. 644.

Adler’s massive criticism leveled at the conduct of the Jewish self-government has often turned to be unjustified based on recent historiographical findings. For a discussion of Adler‘s criticism see the previously mentioned edition of the Theresienstädter Initiative: Theresienstadt in der ‘Endlösung der Judenfrage,’ in particular the essays by Miroslav Kárný, “Ergebnisse und Aufgaben der Theresienstädter Historiographie,” pp. 26–40; Wolfgang Benz, “Theresienstadt in der Geschichte der deutschen Juden,” pp. 70–78, Ruth Bondy, “Jakob Edelstein – der erste Judenälteste von Theresienstadt,” pp. 79–87. New research contributions attempt to gauge the options for maneuvering and arrive at differentiated assessments beyond traditional moral concepts that can hardly be applied to ghetto and camp life. In addition to the previously mentioned Svenja Bethke, one should refer here to the works of Dan Diner, see Dan Diner, “Die Perspektive des ‘Judenrats.’ Zur universellen Bedeutung einer partikularen Erfahrung,“ in: Doron Kiesel (ed.), “Wer zum Leben, wer zum Tod...” Strategien jüdischen Überlebens im Getto, Frankfurt a.M. 1992, pp. 11–36; idem, “Jenseits des Vorstellbaren – der ‘Judenrat’ als Situation,” in: “Unser einziger Weg ist Arbeit.” Das Getto in Lodz 1940-1944, Vienna 1990, pp. 32–40. What chances boycott or open resistance by the prisoners would have had, we do not know; we only know the historical facts: Jakob Edelstein was deported to an extermination camp when the camp commandant proved his falsification of prisoner lists in the fall of 1943; a year later, his successor Paul Eppstein was shot by the SS Schutzstaffel.

Construction of the railroad line between Bauschowitz and Theresienstadt. Otto Ungar, Construction of the connecting railroad from Bohušovice, 1943. Památník Terezin, PT 8185.

In 1941 and 1942, the prisoners arrived in the camp on foot. The train ended at Bauschowitz (today Bohusovice in the Czech Republic) station; on the 2.5-kilometer (about 1.5 miles) walk to Theresienstadt, everyone had to carry his or her own hand luggage. The suitcases, the so-called “take-along luggage,” Starting in June 1943, a connecting railroad, which had meanwhile been built by the Jewish prisoners, ran directly to Theresienstadt. had been transported in a separate train car and were received by the guard personnel.

In Theresienstadt, the new arrivals were led through deserted streets to a military barracks, where they had to spend the first night lying on the bare ground. At this collection point for arriving and departing transports, the “Schleuse” [“pass-through”], all luggage was searched for prohibited items such as money, jewelry, cigarettes, coffee, tea, chocolate, medications, and electrical appliances, and confiscated at will by the SS Schutzstaffel, gendarmes, and Jewish ghetto guards for their own use. This was precisely the reason why the “old-established” prisoners had to stay in their rooms; they could have warned the “newcomers” and hidden forbidden things in time. Many of the new arrivals, including Martha Glass, were left with only their hand luggage; they never saw their suitcases again.

The following day the new arrivals were assigned their rooms, in one of the military barracks or in one of the former civilian houses, also called “block.”

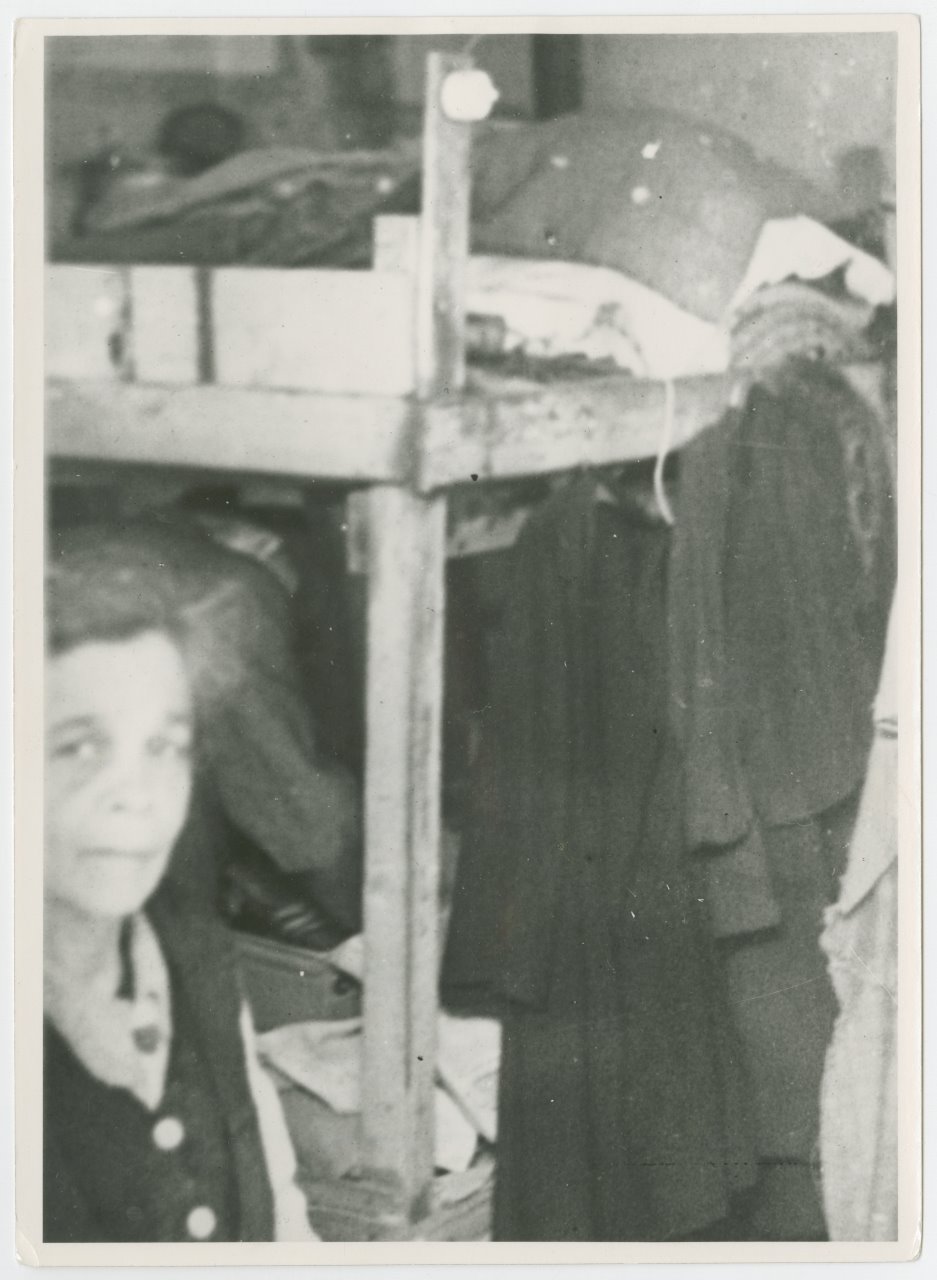

View into the bedroom and living room of a Theresienstadt house. Jewish Museum of Prague, ŽMP, Sb. fot. II/31, č. neg. 20877.

The camp was divided into four districts; the streets were marked L for “Längsstrasse” [“longitudinal street”] and Q for “Querstrasse” [“cross street”]. L 104 (Martha and Hermann Glass’ first address) stood for House 4 in the first longitudinal street.

Married couples and families sometimes lived together, but often men and women were also quartered separately; in the latter case, however, permission was granted to meet during the day. The rooms were poorly lit, and in winter, the inside temperature hardly rose above freezing. In August 1942, there were 41,000–43,000 persons occupying the camp; each resident was entitled to no more than 1.6 square meters of living space, which was just enough for a bed 0.6 meters wide and for stowing away the few remaining belongings. When the majority of the prisoners were deported to the extermination camps in fall 1944, the living space per person rose to 3.05 square meters; in 1942/1943, however, conditions were dreadfully cramped, as Martha Glass impressively describes in her first diary entry. In March 1943, 56,000 people were in the camp. Cf. first diary entry. In the barracks, hundreds of people lived in one room, in the “blocks” often 60 in one room. According to the entry dated October 29, 1944, 140 people initially lived in house L 104. Up to 100 people had to share a toilet, which often did not even have a flush. The attics, also used as sleeping and living quarters due to the acute shortage of residential space, were not insulated against the cold or heat and had neither water nor lighting. After 8 p.m. (9 p.m. in the summer), no one was allowed to leave the house; the nighttime peace extended from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. A building elder was responsible for each barracks and each “block”; the room elders were subordinate to him or her.[XX] The building elder had to ensure peace, order, and cleanliness in the house and had to report every day on the situation in the house, the number of residents, cases of illness, etc.

A youth welfare office located in the camp took care of the children from four to 16 years of age. Many of them were placed in homes, and the number of neglected and criminal children was high. Schooling was irregular and mostly clandestine, as only subjects such as drawing, needlework, and singing were officially allowed. Writing was done on wrapping paper. There were many illiterates among the children, since even before the deportation, they had hardly attended schools anymore.

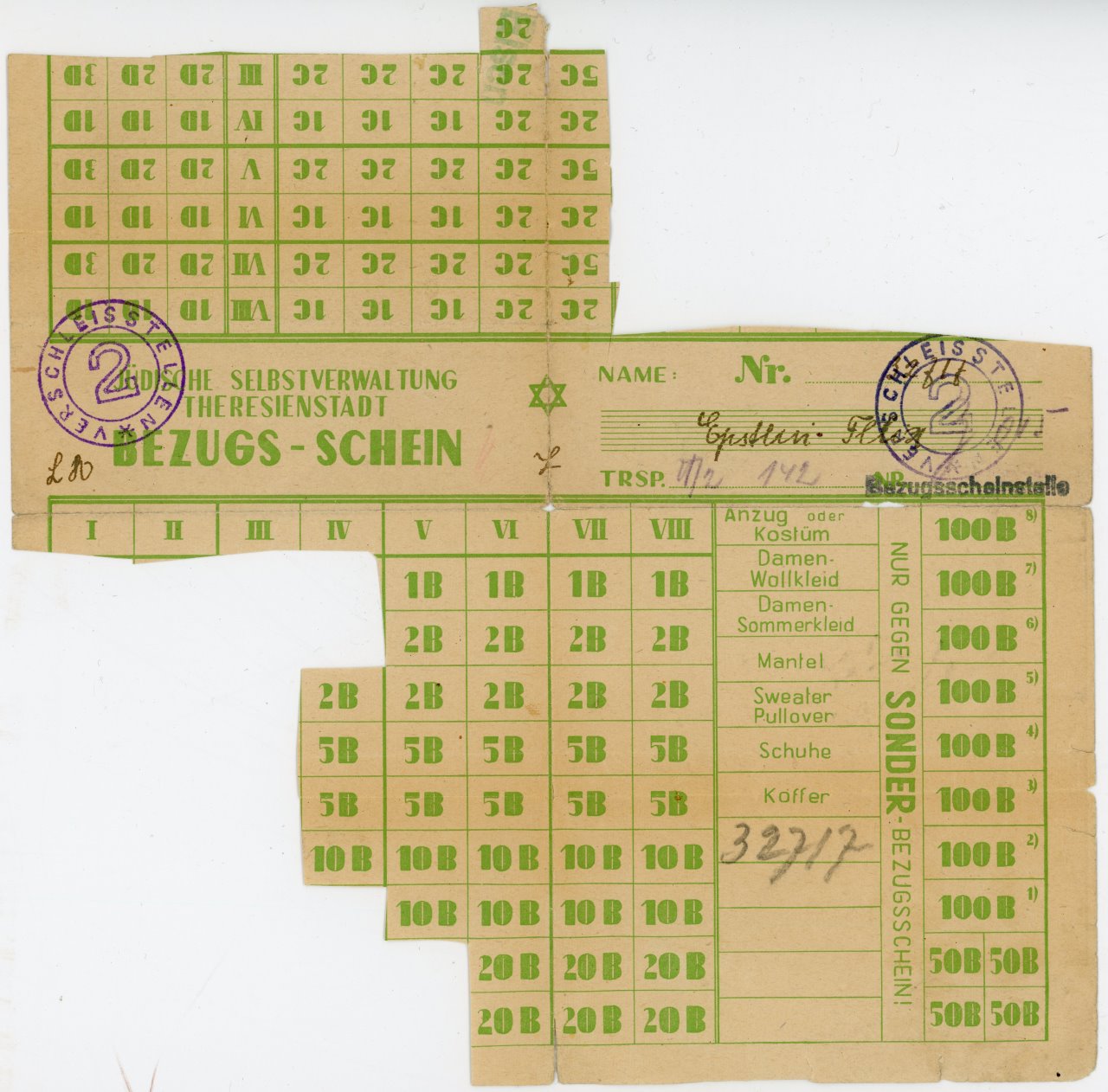

Prisoners between the ages of 16 and 60 had to work ten to twelve hours a day. However, children and old people were also frequently employed for four hours a day. Even the hardest work was in demand, since the workers were entitled to a larger food ration. The people worked to supply the camp, as servants of the SS Schutzstaffel, but also for German companies and the Wehrmacht. They made uniforms and jute bags or worked in the mica splitting plant. The mica flakes were used in electrical engineering and in the aircraft industry. In the repair workshops, up to 800 people were employed in shifts; in some cases, outwork was also done in this sector. From July 1943 on, Martha Glass was called up for four hours a day to darn stockings. At first, she worked together with many other women in one of the barracks designated for this purpose, then doing outwork in her poorly lit kitchen-living room. Cf. diary entries of July 16 and August 11, 1943. The repaired items went to the stores, called “Verschleissstellen” [“wear-and-tear places”] where, incidentally, many suitcases with their contents landed, the very suitcases that had not been returned to the new arrivals at the “Schleuse” [“pass-through”]. “The work of the Jewish prisoners,” the historian Miroslav Kárný notes, “was intended to ensure the economic independence and self-financing of the ghetto and to prove its usefulness for the German war economy.” Kárný, Ergebnisse und Aufgaben der Theresienstädter Historiographie, p. 33. The “Ältestenrat” [“Council of Elders”] hoped to be able to save young people in particular by means of the greatest possible work effort. As was to become apparent later, this hope amounted to a tragic illusion.

The unimaginable hunger made nutrition one of the most important issues in the camp. Every month a meal card was issued, in return for which one could pick up one’s meal from a certain kitchen twice a day. In the mornings, there was only coffee substitute, for everything else one had to fall back on the allocated provisions.

Martha Glass mentions the following information about the composition and quantity of the food in her diary entries: Meat was available in the form of “Hachez,” a watery sauce with a few meat fibers, or meat loaf, which was prepared almost exclusively from bread. As vegetables, occupants ate fodder beets, called “Dorschen,” and sauerkraut, which was usually spoiled. The same applied to potatoes; potato goulash involved a thick soup without meat. Each week, 120 grams of barley, millet, or semolina were available. The only fat the prisoners received was margarine with a high water content, but never more than 200 g per week. No more than 200 g of sugar was consumed per person per week. Skimmed milk was distributed irregularly; there were never any eggs, butter, fruit, cheese, or fish. As the diary shows, the evening meals were tiny and, at least in early 1943, often consisted only of coffee (substitute) and fat. Cf. entry dated March 1943.

For extra work, the administration granted allowances in the form of a little margarine, sugar, or jam. Bread was distributed according to certain categories: S - for heavy workers (500 g per day), N - for normal workers (375 g), L - for light workers (333 g), and K - for sick people (333 g). Food was not only eaten, but also served as a means of payment. Bread and cigarettes had a high exchange value and were traded at fixed prices. 1 kilogram of onions had an exchange value of 60 crowns. For an egg, which was a great treasure, Martha Glass received a whole loaf of bread; for a tin of liver pâté, equivalent to the wages for eight hours of work, 2.5 kilograms of potatoes. Cf. entries dated March 1943, June 19 and November 4, 1944.

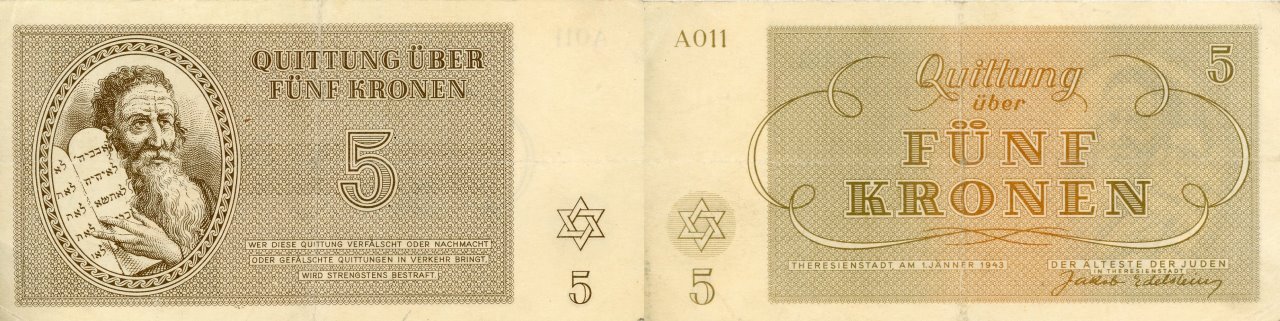

Ten ghetto kronen from Theresienstadt. IGdJ picture database, Collection Müller-Wesemann, NS00047a+b.

Five ghetto kronen from Theresienstadt. IGdJ picture database, Collection Müller-Wesemann, NS00046a+b.

The constant hunger left little room for community spirit and honesty when it came to obtaining food. Petty larceny of food was the order of the day. Anyone who worked in the kitchens, had access to the pantries, or was supposed to distribute food from the provisions among the roommates, stole wherever they could.

Food card for the prisoners. IGdJ archive, estate Felix Epstein, 45.054-07.

Prisoners who held important positions in the camp’s self-administration or had already been high functionaries in Germany were among the “prominent persons” and were given preferential treatment in the camp. They resided and lived in better circumstances than the others did, had their own rooms and furniture, and received larger and special food portions. Whenever onward transports were due, however, even “prominent persons” were no better off than ordinary prisoners, being deported to the extermination camps just as the latter were.

In September 1942, the prisoners received ration coupons entitling them to buy goods. The purchasing entitlement was subject to a certain rotation, and everyone had to wait his or her turn to buy. There were four groups of goods with different point values: Group A = food (120 points), Group B = clothing, underwear (600 points), Group C = dishes, household goods, suitcases (80 points), and Group D = stationery, soap (40 points). As mentioned earlier, the goods in the stores often came from the confiscated luggage of new arrivals or from the estates of deceased persons. In some cases, however, they were also deliveries from foreign companies. In addition to other stores, there were also a butcher’s shop and a pharmacy in the camp, but prisoners were not allowed to set foot in them.

Ration coupon for clothes. IGdJ archive, estate Felix Epstein, 45.054-05.

Every three to four months, people were allowed to bring up to five kilograms of laundry to the laundry shop. Washing facilities were almost non-existent in the houses; the prisoners could take baths and showers only in the camp’s central bathing facility, but only when expressly requested to do so. Due to the poor hygienic and sanitary conditions, epidemics spread. Pest-control measures to combat bugs, fleas, clothes, and head lice, rats, and mice were carried out on a massive scale, The so-called “Entwesung”. but up to 80 percent of the prisoners had lice. The poor nutrition led to protein and vitamin deficiencies and made the people susceptible to disease. The most frequent cause of death was enteritis, an inflammation of the intestines accompanied by severe diarrhea. Hermann Glass also died of enteritis on January 19, 1943. Many prisoners also fell ill with meningitis, diphtheria, typhoid fever, and tuberculosis. Of the 600 doctors who lived in the camp at times, about half were actively practicing their profession. Some 33,500 people perished in Theresienstadt of exhaustion and disease; the number of deaths per day was sometimes 130 to 150.

Funeral ceremonies were never held for individuals, but always for several deceased people of the same religion; Cf. the description of the sister-in-law’s funeral on April 16, 1943. afterward, the dead were cremated and buried in the “Columbarium.” In addition to Jewish funeral services, there were religious services on Shabbat and on Jewish holidays. At the end of 1944, a rabbinate, which had already existed, was officially approved. In order to cover up the mass deaths in Theresienstadt, the SS Schutzstaffel had the “Columbarium” cleared in November 1944. The prisoners had to form a chain of about 200 persons and take the bags with the ashes into a narrow mine passage. Cf. entry dated November 4, 1944. They were told that the ashes would be buried in a Prague cemetery, but in fact, they were later just poured into the Eger (Ohire) River.[XXII]

Since September 1942, prisoners were allowed to write to Germany; permitted were simple postcards that initially could not contain any more than 30 words including the address. Later, the limit on the number of words was lifted. From 1943 on, prisoners were allowed to send a postcard every three months, then every two months. They did not contain anything more than the message that one was healthy and that the sender hoped the recipient was so as well. Complaints, information about the onward transport of relatives, or requests for food were not permitted. On October 6, 1943, Martha Glass complained in her diary about “always the same meaningless text” that she had to convey to her children. The postcards were first censored and forwarded by the Berlin headquarters of the Reich Association of the Jews in Germany Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland and later by the Reich Main Security Office Reichssicherheitshauptamt. Those who violated the regulations received the card back and had to expect not being allowed to send a card again until the next rotation. See entry dated February 16, 1944, Regulations on postal traffic with residents of Theresienstadt.

For a letter, one needed special permission. Permission was granted to accept parcels from Germany up to a maximum weight of one kilogram. With a pre-printed acknowledgement-of-receipt card, one could inform the sender of the receipt. The parcels were opened and searched before delivery. From spring 1944 onward, parcels also arrived through the mediation of the International Red Cross and the Jewish World Congress. Martha Glass received a package from her children in Berlin almost every month, sometimes even more often, starting in March 1943. Starting in the summer of 1944, it was also possible for the younger daughter to send parcels via Lisbon. These parcels contributed not only to her physical but also to her psychological survival in the camp. As long as they arrived, the connection to the outside world did not seem to be completely severed, and Martha Glass was always relieved to find that the children’s addresses had remained the same, so that they were probably doing well, given the circumstances.

According to Hans Günther Adler, the story of the people imprisoned in Theresienstadt is the “story of powerlessness.” Even if each individual thought as an agent, a limit was set to his or her will. Before each deportation to the East, camp life was dominated by paralyzing fear; even if one knew nothing of the systematic mass extermination, there was a notion of terrible hunger and of pogroms. […]& no one knows what it is like in Birkenau. […] It is too gruesome how the families are torn apart & how they will probably never see each other again in life.” Entries dated May 15 and 18, 1944. During the deportations in May 1944, Martha Glass wrote in her diary, “Before Thursday, when the 3rd & last transport leaves, we all will not rest. Then we would have a reprieve until the next transport. Every day in Theresin is a gift.” Entry dated May 16, 1944. This fear, which was added to the hunger and the daily dread of death, was impossible to overcome; the only way was to suppress it, to escape reality for a few hours – with the help of work, familiar rituals, and culture. All actions and reactions in the camp must be understood largely against the background of this omnipresent fear. Adler, Theresienstadt, p. 669. As Martha Glass later told her daughter Ingeborg, she had to promise her husband in Theresienstadt not to take her own life. There will probably have been moments when she found it difficult to keep this promise, especially whenever she learned of another suicide from her Hamburg circle of acquaintances. At the same time, however, the commitment to life probably would have helped her time and again to endure fear and privations and to look for ways to make everyday life more bearable.

After the death of her husband, Martha Glass lived in the closest and most primitive of circumstances with up to nine roommates, yet she kept the habits and rituals of her former bourgeois life as best she could under the circumstances. Holidays such as Christmas, New Year’s Eve, and birthdays were occasions for giving presents and for “celebrating” together. In the language of the diary, the adherence to the habits and ways of life common in the former life is evident: Martha Glass writes of “ladies” who came to visit and experienced an “atmospheric evening” together, of a “laid table” and of “appetizers” that were “served.” A potato was sewn into a sack before it was given away, and even a piece of sugar cube was still considered a treasure. See the entries dated December 31, 1943, January 31, 1944, December 25, 1944. Against resignation and self-abandonment, against an inhumane reality, humane manners and mutual respect were set, apparently rather everyday forms of behavior that received a completely new status under the cruel camp conditions and must be interpreted as signs of a desperate will to survive on the part of the individual and the community.

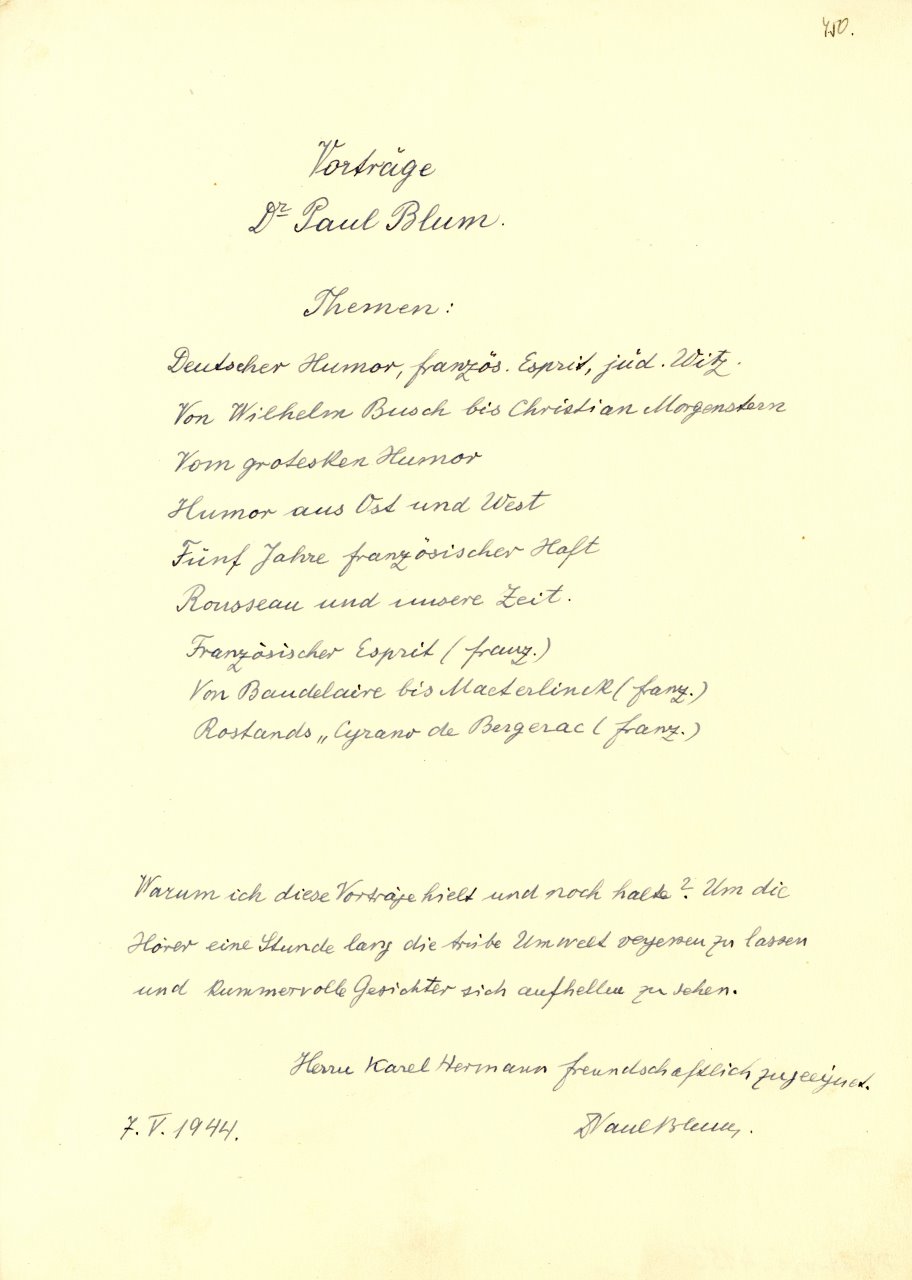

In the camp, the need for and interest in culture was extraordinarily strong: Among the prisoners were a large number of artists and intellectuals who, despite the drudgery they endured during the day, were yearning for intellectual and artistic activity, being able to count on a large audience among the prisoners. Cultural activities had initially been forbidden and they had taken place secretly at best; it was not until 1942 that they were first approved and finally expressly promoted by the SS Schutzstaffel. In late 1942, the “leisure activities” department was established. The equipment of the stages and premises was extremely modest, with the musical instruments originating from confiscated Jewish property in the “Protectorate.” For the performances, the city hall council chamber, the Sokolovna, a hall in the “Magdeburger Kaserne,” two former cinemas, and a coffee house were available. The fare offered was varied, ranging from light entertainment evenings, operettas, and cabaret programs to operas by Mozart, Puccini, Verdi, or Smetana, concerts with classical and contemporary music and theater of character development featuring works by Molière, Shakespeare, Goethe, Shaw, or Hofmannsthal.

Hans Krása’s children’s opera Brundibár under the direction of the composer saw more than 50 performances. Hans Krása was born in Prague in 1899. The children who took part in his opera had to be replaced again and again, since almost all of them were deported to the extermination camps during the performance period. Viktor Ullmann wrote, among other works, the opera “The Emperor of Atlantis or Death abdicates” (“Der Kaiser von Atlantis oder Der Tod dankt ab”) Immediately prior to the premiere, Viktor Ullmann was deported to Auschwitz. in Theresienstadt; at the same time, he directed the “Studio for New Music” [“Studio für neue Musik”], in whose concert series the young composer Gideon Klein, also highly talented as a pianist, presented his own works. Pavel Haas, a student of Leo Janáček, composed numerous piano pieces and an étude for string orchestra. The conductor Karel Ančerl founded a string orchestra, and Rafael Schächter staged several operas with great success. The pianist Bernhard Kaff and the violinist Egon Ledeč (Ledeč-Quartett) were among the most famous virtuosos in the camp. The musicians mentioned above were active members of the “leisure activities” department. They were deported to Auschwitz in October 1944; with the exception of Karel Ančerl, none of them survived. The jazz pianist Martin Roman Born in 1906. was not only a participant in Kurt Gerron’s cabaret “Das Karussell,” [“The carousel”] but also the leader of the “Ghetto Swingers,” a jazz band. Carlo S. Taube conducted the Stadtkapelle [city orchestra], an orchestra comprised of 40 members, and Karl Fischer several choirs. The Central Library, a lending library, contained approximately 50,000 volumes, most of which the SS Schutzstaffel had confiscated in the former Czechoslovakia. Scientific lectures and readings were offered, often held in attics and privately organized. The most prominent visual artists were Fritz Taussig (Fritta), the director of the drawing studio, Peter Kien, Otto Ungar, and Leo Haas. Fritta and Kien, who also illustrated the reports of the “Ältestenrat” [“Council of Elders”] for the SS Schutzstaffel, were murdered in Auschwitz; Ungar died shortly after liberation; and Leo Haas survived. Leo Haas, born in Silesia in 1901, died in East Berlin in 1983. He was arrested in Theresienstadt in July 1944 because of his drawings, whose motifs were taken from camp life, and deported to Auschwitz in October 1944. Before that, he was able to hide about 400 of his works; after liberation, he took possession of them again. Many people painted and wrote poems on all kinds of occasions. Cf. entries by Martha Glass, New Year’s Eve 1943 / 44 and April 9, 1944. In late 1942, a coffee house was established, which was open from 10 a.m. to 7:30 p.m. Anyone who wanted to go there needed a (free) admission ticket and was allowed to stay for two hours. For two crowns one was served a cup of coffee; from 2 p.m. on, a small orchestra played light music and the attendees listened in silence.

Leo Haas, Technical office in the camp, 11.2.1943. Památník Terezín, PT 1886, © David Haas, Daniel Haas, Michal Foell Haas, Ronny Haas.

Censorship was barely practiced, and it appeared as if there were fewer limits in the camp at least in terms of artistic freedom than before the deportation. After the “seizure of power,” the Nazis had excluded Jewish artists and Jewish audiences from the German cultural sphere and banned them from performing German composers and playwrights. In the Theresienstadt setting at the time, almost everything was allowed, even American jazz and swing, which the Nazis had branded as “degenerate.” However, this supposed liberality once again showed the boundless cynicism of the Nazi rulers: While their extermination machinery was already operating at full speed, they managed to pretend to be magnanimous to their victims in the cultural field, especially since they had recognized that the culture in the camp could be used propagandistically for their own purposes.

The numerous cultural activities taking place in the camp later gave the impression that everything had “not been so bad” in Theresienstadt. If one takes a closer look at the camp conditions, however, this assumption proves to be false. No theater performance, no concert, no lecture, no reading – no matter how impressive – could allay imprisonment, hunger, disease, and fear any longer than the duration of the performance. Once a passionate concertgoer and theatergoer, Martha Glass also took advantage of the cultural offerings in Theresienstadt. In her diary, she mentions 22 events. However, there were also times when hunger and depression stifled any desire for cultural entertainment in her. Cf. entry dated January 31, 1944.

As long as there was no certainty about the conditions in the “East” and there was still a spark of hope to survive the camp, the need for art did not dry up; when the terrible truth of the Shoah was revealed with the return of prisoners from the extermination camps in April 1945, no more events took place in Theresienstadt.[XXIII] Up to that moment, however, those events gave consolation amidst emotional distress and evoked those cultural-educational traditions that had once shaped the prisoners’ cultural identity:

With the disappearance of civic order, many whose self-esteem was derived from status, property, and other external circumstances in a normal society lost all ground. As soon as they saw themselves separated from an environment that preserved them, the obliteration took place. The difference between culture and civilization became clear. Most of the pleasures of civilization were taken away – what remained was the possibility of culture. Although culture can only thrive if it is allowed to express itself in an objective world, its foundation lies in the personality that is able to create and feel it. The person of culture who achieves something that rises above animalistic ability is secured and fostered by the goods of civilization and an existing culture, but is not created by them per se. Such an individual has once realized culture in him or her and continues to work on it. Someone like that can hold one’s own in Theresienstadt.” Adler, Theresienstadt, p. 677.

Hans Krása, Brundibár. Scene of the children’s opera in the propaganda film Theresienstadt. Yad Vashem Photo Archive, Jerusalem. 2977- 175a.

The importance of culture in times of distress is clearly demonstrated by the example of the Theresienstadt camp. For those prisoners who had internalized it because of their upbringing and education, it was an invaluable source of strength in the face of Nazi barbarism, which went after everything that belonged to its victims, after their material and spiritual possessions, their human dignity, and their lives. In the camp, according to Milan Kuna, culture provided a “not inconsiderable amount of social warmth,” “without which life would freeze”; in it [i.e., culture], “memory and biographical self-assurance” crystallized, “spontaneity and self-determination, community experience and self-esteem.” Milan Kuna, Musik an der Grenze des Lebens. Musikerinnen und Musiker aus böhmischen Ländern in nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslagern und Gefängnissen, Frankfurt a. M. 1993, p. 353.

“Music was neither a substitute for entertainment nor a mere diversion after physically exhausting work. For the prisoners, it was the struggle for man as a cultural being, fought with desperate defiance; it was the effort to prove and cement their affiliation with that European cultural tradition from which the masters of the ‘Third Reich’ wanted to tear them away.” Kuna, Musik an der Grenze des Lebens, p. 244.

The fact that the prisoners’ need for culture was misused by those in power to feign “normal” living conditions to the whole world does not change the fact that the cultural work in the Theresienstadt camp constitutes a moving testimony of self-assertion and intellectual resistance.

Public announcement of a lecture series. Overview of the lectures – Dr. Paul Blum, 7.5.1944. Památník Terezín, Herrmann-Collection, PT 4155, © Zuzana Dvořáková.

By order of the SS Schutzstaffel, the self-administration had to have the streets repaired and marked with “correct” street names beginning in late 1943. The body had to see to it that green areas with flowerbeds and a playground were laid out, house facades were painted, the food distribution points were renovated, a prayer room and actual theater halls were built, and the accommodations of the Danish and Dutch nationals as well as “prominent persons” were transformed into “showcase residences” on the inside as well. The “ghetto” was henceforth called the “Jewish settlement area,” the ghetto guard called itself the “communal guard,” and the columbarium was designated as the “urn grove.” Day orders to the prisoners were issued as “messages by the self-administration.” In the summer, prisoners were now allowed to stay outside until 10 p.m. In the specially built music pavilion on the town square, the Stadtkapelle [city orchestra] regularly gave promenade concerts. Martha Glass noted, “One feels as if staying at a beautiful health resort & no longer recognizes the dirty Theresin, as it was only half a year ago.” Entry dated June 23, 1944. Theresienstadt had been designated a “model ghetto” by the SS Schutzstaffel and was now to be used to refute the information leaked to the public about the atrocities in the concentration and extermination camps. The transformation of the camp, or more precisely, of a camp section, into a “model settlement” was a monstrous deception maneuver by means of which the Nazis sought to conceal their true intentions, the murder of millions of European Jews.

The most important reason for the “beautification campaign” had been the announcement of foreign visitors. After previous visits by SS Schutzstaffel functionaries, representatives of the German press, and the German Red Cross DRK, an international commission arrived in Theresienstadt for the first time on June 23, 1944, after seven months of preparation, in order to get a first-hand impression of the situation of the Danish prisoners. It consisted of two Danes (the head of the political department of the Danish Foreign Ministry and a representative of the Danish Red Cross) and a Swiss delegate of the International Red Cross (IRK). On the German side, camp commandant Fram, the SS Schutzstaffel, representatives of the Foreign Office and the German Red Cross, and, being the only Jewish representative, Paul Eppstein were in attendance. The visitors walked along the footpaths that had previously been scrubbed with soap by the prisoners, and attended a performance of Krása’s children’s opera Brundibár as well as sports events. They were able to see how the prisoners were handed bread with white gloves, and how plentiful portions of food were distributed. The school was closed “by chance” because the children, as the explanation went, were on “vacation.” None of the German and Czech prisoners was allowed to talk to the strangers, and the commission only asked the Danes and employees of the Jewish self-administration some questions. Cf. entry dated June 23, 1944. For the prisoners, the result was devastating, without them even suspecting it. The Commission had been successfully deceived; no one had taken note that behind the plastered facades, people were living in the most abominable accommodations and that many areas of the camp had been left out during the tour.