The history of Jewish everyday life is an intimate, personal history focusing on the individual and on Jews outside of public life. Alltagsgeschichte the history of everyday life studies how social and cultural changes have affected subjective experience, giving priority to the individual.

In the Hamburg region, Jewish everyday life and family life began in the 16th century with the settling of a Jewish community, and it is closely tied to the towns of Hamburg, Altona, and Wandsbek. As in many other urban centers in Ashkenaz, Jewish life in the Hamburg region shows cultural and social peculiarities from its beginnings until the present day. These primarily include two characteristic features: firstly, the Sephardic community influenced Jewish everyday life in Ashkenazi Hamburg throughout the centuries. Secondly, the Hanseatic city of Hamburg’s character as a shipping metropolis shaped Jewish life there. Not only resident Jews, but also those Jews passing through it determined everyday life. The latter spent varying periods of time in the city, but usually did not stay. Among them were eastern European Jews looking for a new home on the American continent in the 19th century and German and European Jews fleeing National Socialism in the 20th century. In the second half of the 20th century it was Jewish Displaced Persons (DPs) who initially shaped Jewish everyday life and family life in Hamburg until the arrival of Jewish quota refugees from the former Soviet Union in the 1990s.

Writing the history of Jewish everyday life in Hamburg remains a tenuous task due to the problem of finding sources. While the rich source material on some specific topics has made it possible to draw a fairly conclusive picture of Jewish everyday life — by using accounts written by Glikl van Hameln and Altona Rabbi Jakob Emden, for example — other parts of Jewish everyday life not concerning prominent figures, but peddlers, petty shopkeepers, and travelers in transit remain unknown due to a lack of sources.

Throughout the centuries Jewish family and everyday life was influenced by natural, social, political, and economic circumstances. The question where Jews were permitted to settle and take up residence significantly shaped Jewish everyday life until legal emancipation in the 19th century. Circumstances varied considerably from one territory to another, as the example of the Hamburg area clearly shows. The dukes of Holstein-Schauenburg granted a more favorable legal status to Jews in their town of Altona than did the neighboring city of Hamburg. Therefore many Jews dwelled only temporarily in Hamburg in the early modern period. Sometimes Jews from Altona only came to the city to work and left in the evening. According to the memoir by Glikl van Hameln, these men risked being robbed on their nightly way home.

Discriminating anti-Jewish laws not only limited Jewish families in their mobility, but also economically. A number of the Sephardic Jews resident in Hamburg were active in banking and in wholesale or overseas trade and thus enjoyed a comfortable lifestyle. Yet the majority of the Sephardic congregation’s members were by no means wealthy, as a list of congregation members’ contributions from the 17th century proves. A large number of Sephardic Jews worked as shohets, stone cutters, butchers, tobacconists and tobacco spinners or as sugar boilers. Ashkenazi Jews, who only began settling in Altona in the late 16th century, initially were the smaller Jewish community compared to the Sephardim. Both groups were equally strongly represented in trade, however, which in turn shaped the everyday life of their families. Due to their work as tradesmen, men traveled in their Medinah (Hebrew for area of trade) from Sunday to the beginning of Shabbat on Friday afternoon, depending on their kind of work. It was not unusual for tradesmen to be absent from home for weeks while traveling for business. Meanwhile women raised the children and ran the household; in many cases they also ran the business for their husband while he was away.

Until the end of the 19th century – and in poor families long after that – women thus had a share in earning the family’s living, albeit in different areas of trade. One well-known example of a self-employed Jewish woman is Glikl van Hameln, who traded in a variety of different goods. Her memoir provides a vivid impression of the everyday life experiences by a Jewish woman from the Hamburg area and her family. Like Glikl van Hameln, women engaging in trade became travelers, many among them widows who earned their living in this way.

Bertha Pappenheim

dressed up as Glikl van

Hameln. Painting of Leopold

Pilichowski.

Source: The painting's original is lost.

Reproductions are to be found in the first calendar of the Jewish Association of

Women Jüdischen

Frauenbundes (1925) as well as

in the journal of the Jewish

Association of Women Jüdischen

Frauenbundes (Issue 4, April

1932). Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Another challenge resulting from the long business travel undertaken by men was their long separation from wife and children. As we know from the rabbinical response literature from Hamburg, the long absence from home often tempted husbands to have extramarital affairs. However, this certainly was not particular to Hamburg.

Before Hamburg’s Jews were given civic rights in 1861, the authorities decided not only in which towns Jews were allowed to settle, but also where in town, i. e. in which streets and quarters Jews were able to settle and reside. Three quarters of all Hamburg Jews lived in the northern part of the Neustadt [New Town] and in the Altstadt [Old Town], for example. In Altona and Wandsbek there were no specific neighborhoods in the early modern period, but there was a noticeable clustering of Jewish residences around the synagogues. Living in close proximity to the synagogue was of great importance in order to be able to walk to it on the Shabbat. Prayer in the synagogue shaped the everyday lives of Jewish men and women equally and yet differently. While devout men met daily in the synagogue for prayer, Jewish women visited the synagogue for prayer service on the Shabbat along with the men. In Orthodox synagogues such as the Alte and Neue Klaus-Vereinigung Klaus: school on Peterstraße women prayed separately from the men. In the Reformed synagogues of the Tempel Association Neuer Israelitischer Tempelverein (1818) founded in the 19th century women and men still sat separately during prayer, but they were not separated by a screen as is common in Orthodox congregations.

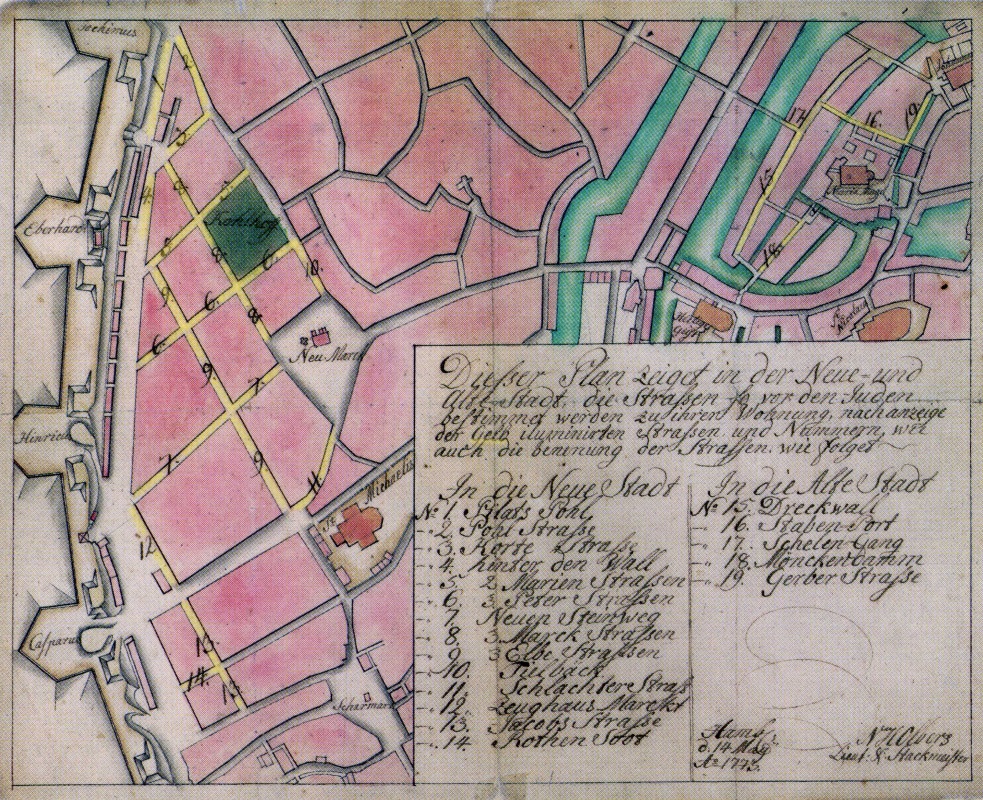

Although no written record restricting Jews in their freedom to settle in Hamburg survives, a map made in 1773 shows that Jews life was spatially limited to a small number of places. In the early modern period, Jewish residences were spread out over 13 streets and a market square in the Neustadt[New Town] and three streets in the Altstadt. The lack of written regulation repeatedly caused conflict between Jews and non-Jews.

Residential area of Jews in Hamburg's Neustadt [New

Town], 1775

Source: Alles

begann mit Ansgar. Hamburgs Kirchen im Spiegel der Zeit. Eine Ausstellung

der Pressestelle des Senats der Freien und Hansestadt Hamburg, Hamburg 2006,

p. 52, Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

In Altona Jews by no means lived in isolation from their non-Jewish neighbors. Jews lived next door to non-Jews, both had close and extensive contact and did business with each other or entered into business partnerships. Sometimes Jews and Christians even shared residential and commercial buildings. The shared use of residential and commercial space required a high degree of willingness to compromise on both parts. Business partners had to negotiate access to the business premises on the Shabbat or on Sundays for members of the other faith, for example. Thus a separate entrance allowed access to the business premises for the Christian business partner on the Shabbat, for example. There are records about a case in Altona in which a Jewish merchant asked the congregation’s rabbi, Ezechiel Katzenellenbogen, for permission to open his linen weaving mill, which he ran in partnership with a Christian, on the Shabbat for his Christian customers. The area of business – like hardly any other – created contact with the non-Jewish environment. Due to their commercial activities, Jewish men traditionally came in contact with non-Jews in their everyday life more frequently than Jewish women did. The places where they encountered non-Jews included streets, the market square, but also taverns. In Hamburg as elsewhere, taverns were among the preferred places for making business deals. One of these taverns was the “Schiffergesellschaft” in Hamburg, where Jewish and non-Jewish merchants came together, drank together, and did business.

The so-called Judenbörse, Elbstraße in

Hamburg's Neustadt [New Town],

Friedrich Strumper († 1913), 1901

Source: Otto Bender,

Die Hamburger Neustadt: 1878- 986. Stadtansichten einer Photographenfamilie,

Hamburg 1986, pp. 26-27, Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

The fact that Jews and Christians shared residential space is documented in reports written by Altona rabbi Jakob Emden. He reports that houses could change from a Christian to a Jewish owner and vice versa when they were sold. We know that Jakob Emden bought a house from a non-Jew. The communal authorities referred to house acquired or inhabited by Jews as “Judenhäuser” [“Jewish houses”]. On the outside, Jewish houses differed from Christian ones by a Mesusah mounted on the door frame. On Jewish holidays, houses were also recognizable as Jewish due to the display of ritual objects. During Sukkot, a Sukkah identified a house as Jewish, for example. Inside the house, religious ritual objects such as a Menorah and a Hanukkah lamp Eight- or nine-branched candelabrum lit during the Hanukkah holiday. and a kosher kitchen were indications of the Jewish rite. Larger houses even included prayer rooms and in some exceptional cases a synagogue, as was the case in Jakob Emden’s house in Altona.

In contrast to Frankfurt am Main, where the Jewish population lived in close quarters in a ghetto until well into the 19th century, their living situation in early modern Altona was relatively comfortable. Residential buildings were not exclusively private – as was typical for merchant families – but also public and thus part of the business. Not only were the lines between family life and commercial life blurred in the living quarters, they also housed a large number of family members and thus fulfilled an important social function. Widows usually lived in the household of their married children, unmarried siblings in the household of their married family members. Such houses not only accommodated several generations of the families that owned them, but also the domestic servants living under the same roof with them.

Moreover, Jewish family life in Hamburg, Altona, and Wandsbek has always been characterized by movement, immigration, and the welcoming of new congregation members from other European regions. It took its beginning with the settlement of Sephardic Jews in the late 16th century. In both their habits and religious practice, they differed considerably from the Ashkenazi community. In everyday life these differences manifested themselves in their different everyday and family languages. While Sephardic families communicated in Portuguese and (in few cases) in Spanish, Ashkenazi families spoke (Low) German and Yiddish. In addition to the Sephardic Jews, eastern European Jews also were among those Jews seeking shelter in Hamburg, as Glikl van Hameln reports. Her family had “taken Jews from Poland, who had fled to Hamburg and were ill, into their house and cared for them.” Robert Liberles, An der Schwelle zur Moderne: 1618-1780, transl. Alice Jakubeit, in: Marion Kaplan (ed.), Geschichte des jüdischen Alltags in Deutschland vom 17. Jahrhundert bis 1945, Munich 2003), p. 65..

The legal emancipation of Hamburg’s Jews in 1861 drastically changed Jewish everyday life and family life. First of all, in the course of emancipation the traditional Jewish neighborhoods dissolved in the 19th century. Between 1870 and 1930, new middle class neighborhoods with a large share of Jewish citizens emerged in Hamburg. About 40 percent of Hamburg’s Jews, a large part of whom were secular or Liberal Jews, lived in Harvestehude and Rotherbaum around the turn of the century. Their increasing move to middle class neighborhoods reflects the social and economic ascent of Hamburg’s Jews in the 19th century. Meanwhile Orthodox Jews largely remained in the Grindel and Neustadt [New Town] neighborhoods and continued to engage in petty trade. In 1925 Jews still accounted for 15 percent of inhabitants in these neighborhoods. The Orthodox Jewish inhabitants of the Grindel district maintained a different religious practice and lifestyle than the secular Jewish inhabitants of predominantly middle class neighborhoods such as Rotherbaum and Harvestehude did. In the 1920s, houses in the Grindel district were still recognizably Jewish on the outside, for example.

The modern age saw the breaking up of traditional family structures according to which Jewish family life was different for men and women. In the course of the 19th century, a change occurred as women began to play a different role in both society and the family. According to Jewish tradition the woman alone is in charge of the household, which primarily means keeping a kosher kitchen and planning for the religious holidays. While domestic servants were invariably Jewish prior to emancipation, even Orthodox families employed non-Jews in their households by the early 20th century.

Secularization and assimilation into the middle class offered Jewish men and women the opportunity to participate in the non-Jewish world to a larger extent and to break free from the Orthodox Jewish milieu. This becomes evident in the lively participation of Jews in the emerging network of associations, for example. As a result, the distinction between the Jewish population and the non-Jewish social majority increasingly disappeared.

Nevertheless the Jewish population differed from the Christian majority population – as is typical for minorities – in their social and cultural characteristics, as a look at the birth rate among Hamburg’s Jews shows. In 1901 and 1902, there were 16.2 births per 1,000 Jewish Hamburg citizens while there were 24.1 births among the same number of Protestants, and the national average was 36.5. The relatively low birth rate among Hamburg’s Jewish population compared to the national average primarily reflects the difference between urban and rural areas. At the same time the birth rate among the Jewish population declined earlier than it did among the non-Jewish population. This development is an indicator of both the degree to which the Jewish population had joined the middle class and their education levels. In early 20th century Hamburg, the birth rate was generally lower among individuals with a higher level of education and economic prosperity. The degree of prosperity among the Jewish urban population is also illustrated by their lower mortality rate in comparison to the overall population. Among the Jewish population it was at 10.7 percent while it was at 16.2 percent among Hamburg’s overall population.

Despite all the major changes that had occurred, most Jewish marriages were arranged well into the 19th century, and in Orthodox families this tradition continued even longer. The family ensures the passing on of the Jewish tradition. Belonging to Judaism, the status of one’s family, and the size of the dowry all influenced the choice of a spouse. According to Jewish rite, the size of the dowry was recorded in the Ketubah (prenuptial agreement). The choice of the spouse was meant to ensure the survival of Jewish tradition, which is essential for a minority. Yet its purpose was also to confirm the economic prosperity one’s own family had achieved. It was primarily wealthy families who arranged their children’s marriages. In less prosperous families, young people often had to postpone marriage until they had found an occupation that earned them a living.

When the modern age began in the 19th century, the strict division between the Sephardic and Ashkenazi communities began to dissolve. It became particularly evident in the growing number of marriages between Sephardim and Ashkenazim since the mid-19th century.

The dividing lines between the Jewish and the Christian population also became increasingly blurred. At the beginning of the 20th century an increasing number of Jews living in major cities chose a non-Jewish spouse. In 1866, shortly after they had been grated civic rights in Hamburg, 13.1 percent off all Jewish brides and bridegrooms exchanged wedding vows with a non-Jewish partner. By 1928 their number had risen to 35.58 percent. With regard to Jewish-Christian marriages Hamburg was at the top nationwide, outnumbering even Berlin, home to the largest Jewish community in the Weimar Republic.

One side effect of this trend was the decrease in the number of Jewish congregation members in Hamburg. More than half of the children born to parents in a Jewish-Christian marriage between 1885 and 1910 were baptized and therefore not members of the Jewish congregation. While the share of Jews in Hamburg’s total population in 1871 was 4.1 percent, 39 years later, in 1910, it was only 1.9 percent. The choice of a non-Jewish spouse did not always meet with parental approval, and especially in Orthodox families the choice of a non-Jewish spouse was explicitly discouraged.

The disappearing dividing lines between Jews and non-Jews met with both acceptance and rejection on the non-Jewish side as well. The years of integration and social participation were never free of antisemitic agitation. The family offered protection from the antisemitism of the non-Jewish environment that came along with the process of assimilation into the middle class.

When the National Socialists came to power, the everyday life and family life of Hamburg’s Jews changed abruptly.

Group portrait showing the Carlebach family, mother Lotte Carlebach with

nine children, before the war

Source: Yad Vashem, Photo Archive 1869/243, with kind permission of Prof. Miriam Gilis Carlebach.

From now on the everyday life of Jewish families was marked by a constant state of emergency. National Socialist policy during the prewar years was aimed at marginalizing the Jews socially and economically. Henceforth Jews were only able to participate in social life if they were willing to face hostility and the risk of physical assault. National Socialist antisemitic legislation had a grave impact on Jewish everyday life. The nationwide ban on shekhita passed in April 1933 meant a restriction of religious practice and dietary habits for the Jewish community. If Jews wanted to continue to observe the religious dietary laws, they either had to give up meat entirely or buy kosher meat imported from abroad at a high price. In Hamburg the Jewish community responded by storing kosher meat in a refrigerated warehouse and by importing kosher meat from Denmark. The rabbi in charge of the Israelite Hospital responded to the lack of kosher meat by giving patients permission to eat anything – except pork.

Jews were excluded from non-Jewish associations, foundations, schools and other areas of social life as early as summer 1933. The era of the Jews’ diverse participation in the organizations of Hamburg’s civil society had thus come to an end. By means of this policy of social and economic boycott the National Socialists intended to make the Jewish population leave the country. The economic boycott and numerous professional bans (“Aryan articles”) led to the gradual impoverishment of the Jewish population. Many Jewish families were torn apart under this social and economic pressure. In Hamburg, a city with a particularly high number of Jewish-Christian marriages, the racist Nuremberg Laws passed in September 1935 caused veritable tragedies. The National Socialist regime put massive social and economic pressure on the Christian spouses to divorce their Jewish partners. On the other hand, families still offered refuge and retreat from steadily increasing persecution. While the younger generation in particular sought refuge abroad, older family members remained in Hamburg, defenseless and at the mercy of their persecutors. Between 1933 and 1941 an overall number of ten to twelve thousand Jews were able to flee from Hamburg to safety abroad. Among them were about one thousand children who escaped to England by means of the Kindertransport.

While many of Hamburg’s Jews desperately sought safety abroad, Hamburg itself temporarily became a refuge for Jews from other German regions seeking the anonymity of a major city. Jewish refugees passing through Hamburg had great difficulty in finding accommodation in a hotel room. A considerable number of private hotels further aggravated the situation for Jewish refugees. We know from memoirs that a hotel near the train station banned a Jewish couple from eating in the hotel restaurant. They had to eat in their room. Other hotels in Hamburg refused rooms to Jewish guests. Restaurants refused service to Jewish patrons.

When Jewish property owners were robbed of their property following the November pogrom of 1938 and Jewish tenants lost all protection in April 1939, housing available for Hamburg’s remaining Jews became increasingly scarce. Many houses that had been owned by the same Jewish family for generations were expropriated after the November pogrom. This ended the tradition of long-established Jewish neighborhoods in Hamburg. In 1941 National Socialist authorities deprived the Jews of the last private spaces remaining to them when they forced them to move into buildings designated as “Judenhäuser” [“Jewish houses”] The housing situation of the Jews who had remained in Hamburg worsened further after the beginning of the war and especially during the air raids by the British Royal Air Force. When a lot of residential buildings were destroyed during air raids in the summer of 1943, Jewish tenants had to vacate 400 rooms in order to make them available for non-Jews. The displaced Jewish tenants were supposed to be gathered in areas to the North and West of the Grindel district.

In this situation of social isolation and persecution, the Jewish congregation gained new significance as a social center. From now on it was not just at the center of religious life, but it also offered institutions of support to lessen the plight of its members. Until the end of November 1941, these included free meals for poor congregation members at the home on Innocentiastraße and as of 1941 the soup kitchen [Volksküche] at Schäferkampsallee 27. In addition to free meals, the Cultural Associationy Kulturbund offered entertainment programs for the victims of persecution in its community building at Hartungstraße 9.

While there had been 16,963 Jews in Hamburg in 1933 (1925: ca. 20,000), the Jewish congregation had shrunk to 7,547 members by October 1941. At this point there were 1,036 interdenominational marriages existing in Hamburg, temporarily protecting Jewish spouses from deportation. If the non-Jewish partner filed for divorce, however, the Jewish partner ran the risk of being deported to an extermination camp. Between October 1941 and February 1945, a total of 5,848 Jews were deported from Hamburg to the extermination camps in occupied Poland. So far the names of 8,887 Hamburg Jews murdered in the Holocaust have been identified. The overall number of victims from Hamburg is estimated at 10,000.

Immediately after the end of the war, on July 8, 1945, twelve survivors gathered in Hamburg in order to found a new Jewish congregation that initially counted 80 members. In October 1945 its newly established board passed by-laws that broke with the tradition of maintaining three differently oriented congregations and instead created a unified congregation of moderately Orthodox orientation. Initially this new unified congregation aimed to provide a religious “home” for survivors, but it also offered support for filing claims for restitution and compensation. The fundamental question whether Jewish life should be rebuilt and rooted again in the “country of the perpetrators” was of secondary importance compared to the urgent matters of everyday life. The provisional character of the unified congregation ended when it was granted the status of a statutory body in 1948. From now on it performed the traditional tasks of a congregation – worship, funerals, welfare, and religious education. Apart from the members of the Jewish congregation there also were Jewish DPs in the Hamburg area after the war. Most of them were from eastern Europe and had survived the crimes of National Socialist dictatorship, among them a large number of minors. In June 1946 the British military government counted a total of 206 Jewish DPs aged between 18 and 46 in the Hamburg area. In contrast to the German Jews, it was not the German authorities but the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) that was responsible for DPs. This resulted in obvious differences in the provision of social welfare and aid for German and non-German Jews. After the war food rations allocated to German Jews were much smaller than those for Jewish DPs, for example. When permission to butcher according to the rules of shechita was granted in 1947, it once again became possible to observe Orthodox dietary laws. Another milestone in the reestablishment of Jewish life in postwar Hamburg was the opening of the new synagogue at Hohe Weide on September 4, 1960. In order to ensure the religious education of their children, the Jewish congregation founded a daycare center in the 1960s and also offered various activities for children and youths.

Children at the Jewish daycare center, Hamburg, 1960s

Source: Picture

Database of the Institute for the History of the German Jews, NEU00001a,

Jewish Congregation

Hamburg, album no.4.

In light of the congregation’s drastically ageing population, children’s and youth programs were especially important. However, the Jewish daycare center had to be closed in 1979 due to low enrollment.

When the Iron Curtain fell in 1989/90, this once again changed the character of Hamburg’s Jewish community. Since 1989 several thousand Jews from the former Soviet Union have come to Hamburg, altering Jewish everyday life and family life in manifold ways. They had become estranged from Jewish worship in the Soviet Union, yet they eagerly participated in congregational activities, especially in cultural events and leisure activities, but less so in religious celebrations or prayer services. They also added another language to Hamburg’s Jewish community. Its newsletter is now published in German and Russian in order to reach speakers of both languages.

Jewish everyday life after 1990 has also been characterized by greater diversity. In addition to the unified congregation, several other religious associations were founded over the years, including Chabad Lubawitsch (2004) and Kehilat Beit Shira – the Jewish Masorti congregation in Hamburg (2009). The restitution of the Talmud Torah School property to the Jewish congregation in 2002 after years of negotiations made it possible to revive the tradition of combining Jewish religious instruction with a secular education. When the Joseph Carlebach School was newly founded at Grindelhof in 2002, Jewish parents once again were given the option of sending their children to a Jewish school.

Jewish family and everyday life in Hamburg has undergone massive change since the early modern period and yet there is one constant: the migration and integration of Jews from other European countries. The immigrants enriched the everyday lives of the Jews in Hamburg throughout the centuries with other forms of worship and other everyday languages. Thus they have influenced and shaped Jewish life in the Hamburg area in many different yet always substantial ways.

This text is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the work is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute the material in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Stefanie Fischer (Thematic Focus: Family and Everyday Life), Dr. phil., holds a postdoc position at the Center for Jewish Studies, Berlin-Brandenburg. In her current research project, she is examining the post-genocidal relationships of Jewish Holocaust survivors to their former German home towns in the 1950s/1960s. In her PhD thesis, she investigated the interrelationship between economic trust and anti-Semitic violence as exemplified by the German-Jewish cattle dealers between 1919 and 1939.

Stefanie Fischer, Family and Everyday Life (translated by Insa Kummer), in: Key Documents of German-Jewish History, 22.09.2016. <https://dx.doi.org/10.23691/jgo:article-225.en.v1> [March 11, 2026].