The term migration is used to describe different, interconnected processes, especially mobility, immigration and emigration, internal migration, labor migration, seasonal migration, flight and expulsion. Among the most extreme forms of forced migration were the deportation of Jews to ghettos and concentration and extermination camps during the National Socialist regime or the death marches in the months and weeks before liberation in 1944 / 45.

As a port city, Hamburg has a special position in German and German-Jewish history with regard to migration. Jews from very different and in some cases very distant parts of Europe settled in Hamburg. Moreover, it was here that many Jews especially from eastern Europe began their overseas journey.

The beginnings of Hamburg’s Jewish community are linked to the Jews’ expulsion from the Iberian Peninsula at the end of the 15th century. Until the 18th century Sephardic migrants and their descendants shaped the Jewish community in Hamburg. In the neighboring, Danish-ruled town of Altona, another Jewish congregation established itself. Altona pursued a more tolerant policy towards those of different faith than Hamburg did. In the second half of the 19th century Hamburg developed into one of Europe’s most important transit hubs while it grew to become the second largest city in Imperial Germany. The Jewish community grew mostly due to migration from northern Germany. In addition, a significant number of the more than two million Jewish migrants emigrating from eastern Europe to the New World between 1880 and 1914 passed through the port of Hamburg.

In the 1920s, Altona continued to be more open than Hamburg in its policy towards Jewish refugees and migrants who now mainly came from eastern Europe. Between 1933 and 1941 the majority of Hamburg’s Jews managed to emigrate. National Socialist authorities deported most of the Jews remaining in the city to ghettos and extermination camps. Only few Jews returned to Hamburg after the liberation. Most members of the Jewish postwar congregation were refugees and Holocaust survivors from eastern Europe. Since the 1950s Jews from Iran also began moving to Hamburg. After 1989 the congregation started expanding significantly due to immigration from the Soviet Union and its successor states.

The early history of Hamburg’s Jewish community is closely linked with two formative migration movements in Jewish history around 1500 which resulted in a reconstitution of the Jewish diaspora: the migration of Ashkenazi Jews to eastern Europe and the expulsion of Jews from the kingdoms of Spain and Portugal.

Until the 14th century, central Europe and the Iberian Peninsula were the most important centers of Jewish life. Yet Ashkenazi Jews had been expelled or displaced from many cities in central Europe as early as the 13th century. At the end of the 15th century a new center of settlement emerged in the Polish-Lithuanian Empire and soon became dominant. In the German-speaking area of central Europe, Jews were restricted to settling only in certain cities such as Frankfurt am Main. Most Jews lived in small rural communities in today’s southern Germany and its neighboring regions such as Bohemia and Alsace. In northern Germany there were only a few, disparate rural Jewish communities after 1500. In Hamburg the presence of a few individual Ashkenazi Jews is documented only in the course of the 16th century. In 1649 a small group of Ashkenazi was formally expelled from Hamburg. Most of them had fled from Altona to Hamburg in 1627 during the Thirty Years War. Altona belonged to the duchy of Holstein-Schauenburg. In return for a payment of protection money, Ashkenazi Jews were allowed to settle there since the beginning of the 17th century. Thus an Ashkenazi congregation could develop in Altona and prosper thanks to its proximity to the larger port city of Hamburg while initially being less significant than the Sephardic congregation in Hamburg.

The migration to Hamburg of so-called Sephardic Jews, the descendants of Jews from Spain and Portugal, goes back to an edict of expulsion issued by the Spanish crown. In 1492, after the so-called Reconquista was completed and the last Muslims had been expelled, the Spanish royal couple Ferdinand and Isabella ordered the expulsion of the Jews from their dominion. Only those Jews who had converted to Christianity were allowed to remain. However, during the Inquisition so-called Conversos were frequently suspected of secretly holding on to their Jewish faith and were often persecuted. The majority initially migrated to Portugal or North Africa. In the following decades, the descendants of the expelled Jews settled all around the Mediterranean, especially in areas under Muslim rule. Small groups of Sephardic Jews were allowed to settle in Italian port cities such as Venice and Livorno, where they were welcome because of their trade contacts but had to live in separate ghettos. Under pressure from Spain, Jews were formally expelled from Portugal in 1497 yet still tolerated there for many decades. It was only at the end of the 16th century and due to pressure from the Church that massive persecution began. In the 16th century, Jews from Spain and Portugal participated in the exploration and settlement of the New World. Smaller groups found a new home in the Protestant port cities of northwestern Europe. In the booming port city of Amsterdam, the hub of the budding Dutch colonial empire, the most significant and wealthiest Sephardic community in Europe emerged at the end of the 16th century.

In Hamburg there are accounts of Catholic New Christians of Portuguese origin dating back to the end of the 16th century. In the years after 1600 a growing number of these Portuguese migrants openly practiced Judaism, the religion of their ancestors. Although the church and representatives of Hamburg’s merchant class in particular were prejudiced against the new arrivals and discrimination was part of their daily lives, the Sephardic Jews were tolerated. In the first half of the 17th century, three small Sephardic congregations emerged and united in 1652. Apart from the “Turkish-Israelite” congregation "türkisch-israelitische" Gemeinde founded in Vienna in 1737, Hamburg’s Sephardic congregation, which was called the Portuguese congregation Portugiesen-Gemeinde, remained the only one of its kind in German-speaking central Europe until 1800.

The early history of Jewish communities in the Hamburg region shows that processes of immigration and emigration, expulsion and economic migration were closely linked. The early Portuguese settlers in Hamburg had generally not fled Portugal because their lives were threatened, but they were the children and grandchildren of expelled Jews. Quite a few of them travelled to Portugal on business although the Inquisition continued to pose a threat to them. Hamburg was attractive to aspiring merchants because of its proximity to markets in eastern and northern Europe even if there was a higher degree of rejection and discrimination of Jews than there was in Amsterdam.

At the end of the 17th century pressure on the previously flourishing Sephardic community in Hamburg intensified. The city magistrate demanded large cash payments and levied special taxes. Several wealthy families left the city for Amsterdam or the more tolerant town of Altona. After 1700 a growing number of Ashkenazi Jews moved to Hamburg and the neighboring town of Wandsbek. Some of them formally remained registered in Altona in order to avoid losing their relatively privileged status. In 1811 there were 6,429 Jews in Hamburg (4.87 percent of the total population), which was a remarkable number in the central European context.

In the 19th century the Jewish congregations in Hamburg and Altona grew significantly. As part of their incremental emancipation, Jews gained the right of domicile. For members of an economically marginalized group, rapidly growing cities offered attractive opportunities. The embourgeoisement of most German Jews during the middle decades of the 19th century generally coincided with the move to a major city.

While Hamburg’s was by far the largest Jewish community in northern Germany, it expanded much more slowly in the second half of the 19th century than other urban Jewish communities in Imperial Germany did. This was essentially due to a relatively low level of immigration. As in other communities in Germany, most immigrants came from the areas surrounding the city. In contrast to southern Germany and Prussia’s eastern provinces, however, there were relatively few Jews living in the provinces of Schleswig and Holstein, in Mecklenburg, and in the kingdom of Hanover (a Prussian province since 1866) which surrounded Hamburg. By 1871 the number of Hamburg’s Jews had more than doubled from 6,400 (in 1811) to almost 13,800 due to migration and natural increase.

After the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Hamburg became an important port of departure for millions of migrants from German-speaking central Europe leaving for America, although Bremen remained the main port for emigrants. Of the roughly 100,000 Jews emigrating from the German states to North America between 1820 and 1880, it was mostly Jews from the province of Posen who embarked in Hamburg. Jews from southern Germany usually travelled via Le Havre, Antwerp or Rotterdam before the extension of the railroad network. In the 1870s migration to America shifted from central Europe and the British Isles to southern and eastern Europe. Jews from eastern Europe represented a significant share of this transatlantic mass migration. Between 1880 and 1914 more than two million Jews from eastern and East Central Europe migrated mainly to the United States. More than half of the Jewish migrants leaving eastern Europe for America embarked on their transatlantic ship passage in either Hamburg or Bremen. Hamburg became the most important port for Jews and other migrants from the Russian Empire. While Imperial Germany was one of the main transit countries for eastern European migrants to America, it played only a minor role as an immigrant destination in itself. Imperial Germany and its constituent territories, especially Prussia, pursued a restrictive immigration policy after 1880. Russian subjects in particular were isolated during their transit journey. Many migrants travelled in sealed migrant trains from the eastern border to the ports. The account written by young Mary Antin about her journey published in 1899 offers a rare behind-the-scenes glimpse into the transit journey undertaken by a Jewish female migrant. Antin arrestingly describes and comments on the train journey, disinfection at Ruhleben near Berlin, and spending several days in quarantine at the port of Hamburg.

In the early 1880s, the Hamburg-based Hamburg-Amerikanische-Paketfahrt-Aktien-Gesellschaft (HAPAG) and the even larger Norddeutscher Lloyd in Bremen began to systematically develop the passenger market in eastern Europe with the aid of emigration agencies.

Portrait of Albert

Ballin by Enno Kleinert

Source: With the kind permission of: bildarchiv.kleinert.de;

Cuxpedia, CC

BY-NC-SA 2.5.

One of Imperial Germany’s most successful Jewish businessmen, Albert Ballin, played a major role in this process. The son of the owner of a small emigration agency who had immigrated from Denmark, he expanded the shipping company’s operations on the lucrative eastern European market after he became head of HAPAG’s passenger division in 1886. Ballin managed to allay the concerns of both the U.S. immigration authorities and the Prussian government about masses of “undesirable” migrants becoming a financial burden to the state. When a disastrous cholera epidemic killed more than 8,000 people in Hamburg in the summer and fall of 1892, public opinion as well as government authorities in Hamburg and Berlin wrongly held Russian Jews responsible for it. In reaction to these accusations, HAPAG and Norddeutscher Lloyd in the mid-1890s established a network of checkpoints at Prussia’s eastern border where all transiting migrants had to undergo a medical examination and disinfection. Individuals who did not meet the requirements of U.S. immigration laws because they suffered from certain diseases, were considered “insane” or were unqualified for regular employment were denied transit. HAPAG and Lloyd relieved the Prussian government by covering the costs for all medical checks and the repatriation of rejected migrants. In exchange the Berlin government granted HAPAG and Lloyd a monopoly on transit migration from eastern Europe that lasted until 1914. While Norddeutscher Lloyd focused on the territory of the Habsburg monarchy, Hamburg became a hub for migrants from the Russian Empire.

HAPAG’s methods met with harsh criticism from some contemporaries, as the report written by Vorwärts editor Julius Kaliski sharply criticizing the close cooperation between Prussian authorities and HAPAG and Lloyd illustrates. HAPAG stockholders profited from the high price for a ship passage which migrants from humble backgrounds, among them many Jews fleeing pogroms, had to pay due to the lack of competition. However, this criticism was justified only in part. HAPAG offered a relatively high level of comfort to its passengers, especially at the emigration facilities opened at Veddel in 1902, which even included a small synagogue. By 1900, Jewish passengers were served kosher meals during the ship passage. U.S. immigration inspectors repeatedly praised the high standards of hygiene maintained by HAPAG. Hamburg’s Jewish congregation took care of Jewish migrants in transit. Among its key figures was Daniel Wormser (1840-1900), a teacher who in 1884 founded the Israelite Association for the Support of the Homeless Israelitischer Unterstützungsverein für Obdachlose. Among other things he facilitated the provision of kosher food.

When the First World War broke out, shipping to and from Hamburg came to an almost complete standstill. During the war thousands of eastern European laborers worked at its port. Among them were about 100 Jews. When they were about to be deported in early 1919, the Jewish congregations in Hamburg and Altona successfully intervened. With hindsight, the First World War represented a significant turning point in migration history after 1800. Immigration restrictions in many European states and other parts of the world made migration more difficult. At the same time many states “rid themselves” of undesirable minorities. The mass murder of Armenians in 1915 by Ottoman troops is considered the first modern genocide today. During the war millions of people, especially those belonging to unwelcome minorities, were expelled. Especially the traditional center of Jewish settlement in eastern Europe was badly affected. Due to massive destruction and the newly drawn borders in eastern Europe, many war refugees and displaced persons were unable to return to their homeland. In the postwar period, Polish and Russian nationalists systematically attacked Jews. In 1918 / 19, at least 65,000 Jews were murdered in the area of present-day Ukraine and eastern Poland alone. Like many Armenians who had managed to flee the Ottoman troops, hundreds of thousands of eastern European Jews became refugees without the option to return after 1918. Many Jewish refugees were stateless because the successor states to the Russian Empire, the Habsburg monarchy, and the Ottoman Empire often refused granting citizenship to members of unwanted minorities.

After the German defeat the Allies kept Hamburg’s port closed until 1921. Several thousand Jewish migrants transiting from eastern Europe passed through Hamburg in subsequent years on their way to the United States, especially in the years from 1922 to 1924. In 1925 an extremely restrictive U.S. immigration law directed at citizens of eastern and southern European states in particular came into effect. Other countries such as Great Britain, Argentina, South Africa, and Australia also made immigration more difficult. Thus overseas emigration generally no longer was an option for Jewish refugees in and from eastern Europe. Overall more foreign Jews were allowed to immigrate to the Weimar Republic than to Imperial Germany in its entire existence until 1914. Hamburg, too, became home to Jews from eastern Europe and especially Poland after 1918. Many of them were stateless and not all of them registered with the authorities. For the interwar period there is no reliable information on the number of Jewish migrants in transit and the share of Jewish immigrants in the total Jewish population of Hamburg and Altona. Prussia pursued a relatively liberal policy after 1918 and naturalized several thousand Jewish immigrants from eastern Europe.

In the course of the Great Depression many countries introduced more restrictive immigration laws. In 1930, U.S. President Herbert Hoover ordered immigration visas only to be issued in exceptional cases. It was not until 1935 that his successor, Franklin D. Roosevelt, repealed this order. Although Germany had been granted a relatively high annual immigration quota of circa 27,000, it was not fully exhausted until 1939 as a result of the National Socialist rise to power in 1933. However, the 50,000 immigration visas granted to Jews from Germany and Austria in 1939 represented more than 50 percent of total immigration to the United States that year. This extremely high percentage considering the small size of this demographic group gives a vague impression of the misery and desperation in which Jewish refugees escaping National Socialist terror found themselves.

In the first years following the National Socialist rise to power only relatively few Jews emigrated from Hamburg. Most of the early emigrants went either to neighboring countries such as France or the Netherlands or to Palestine, which was relatively easy to reach until 1935. It was only after the November pogrom of 1938 and under massive pressure by the National Socialist terror apparatus that large-scale emigration set in. By 1941 the large majority of Hamburg’s Jews had left their home town.

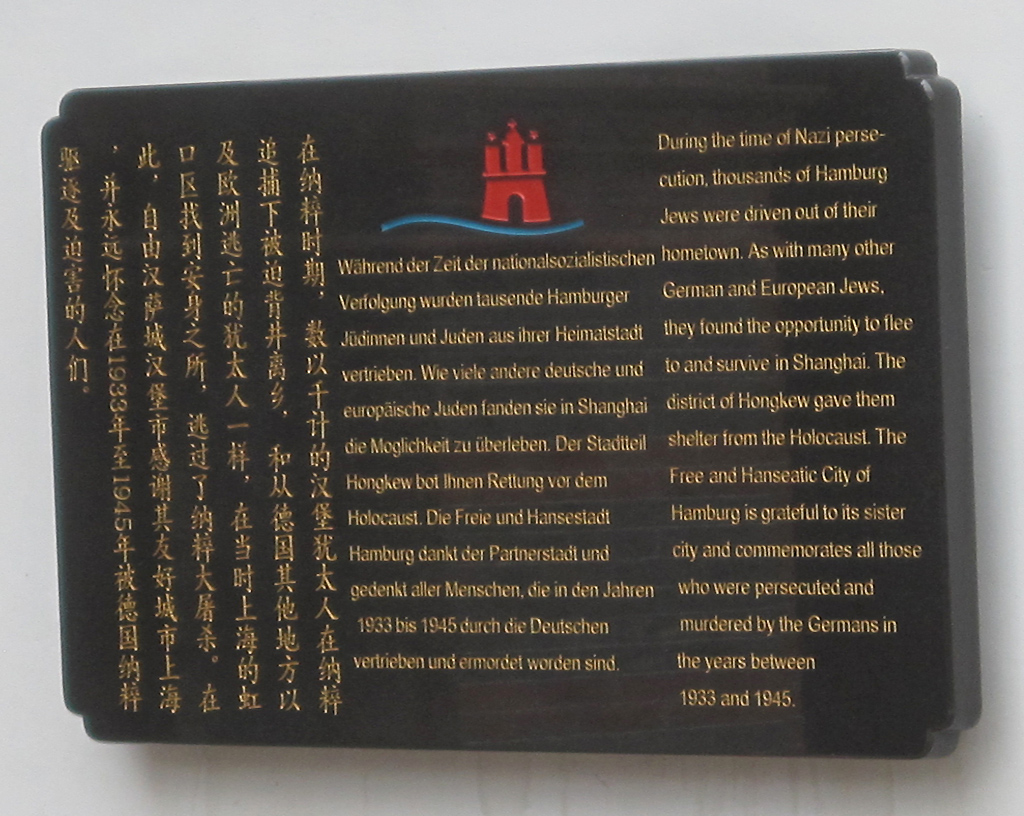

Commemorative plaque in Shanghai remembering the Jews who had to emigrate from

Hamburg

Source: photo: Tobias

Brinkmann, CC

BY-SA 3.0.

Most of them went to the United States, Great Britain or France. The British government granted asylum to German-Jewish children in reaction to the November pogrom. Jewish girls and boys from Hamburg, too, were taken to Great Britain as part of the “Kindertransport” program.

Jewish children from Germany have arrived in Harwich (Essex),

coming from the Netherlands, December 1938

Source: German Federal

Archives, picture 183-1987-0928-501, Wikimedia Commons, CC-BY-SA 3.0 DE.

Overall, between 10,000 and 12,000 Jews emigrated from Hamburg between 1933 and 1945.

Deportations from Hamburg began in October 1941. The first transports went to the Lodz ghetto and to Minsk and Riga. In July 1942 alone, 2,000 Jews from Hamburg were deported to Auschwitz and Theresienstadt in three transports. At the end of December 1942 only 1,805 Jews remained in the city. The Gestapo dissolved the Hamburg Jewish organized community in 1943. A total of 5,296 Jews were deported from Hamburg. Other Jews from Hamburg who had emigrated found themselves back under German control after the outbreak of the war. 542 Jews from Hamburg were deported from the Netherlands, for example. Overall, the names of 8,877 Jews from Hamburg who were murdered in the Holocaust have been verified. The total number of Jewish victims from Hamburg is estimated at about 10,000.

On May 3, 1945 the widely destroyed city of Hamburg was surrendered to British troops. At the time of liberation, only few members of the old congregation still lived in the city, the overwhelming majority of them Jews living in so-called “privileged mixed marriages” [“privilegierte Mischehen”]. In 1945 / 46 several hundred Jewish refugees and survivors moved to Hamburg. Most of them were Jews from eastern Europe. Jewish aid organizations offered support to these refugees. In the late 1940s, the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (Joint) funded a recreation home for children located in the former residence of the Warburg family on the Kösterberg in Blankenese. In 1948 the Organization Rehabilitation through Training (ORT), originally a Russian-Jewish organization, opened a Jewish school for training craftspeople on Rothenbaumchaussee.

For most Jews coming to Hamburg after 1945, the city was primarily a temporary stop on their way to a new homeland, especially to Palestine/Israel and the United States. The Bricha escape organization established in 1944 supported Jewish refugees and survivors on their journey to Palestine. British Mandate authorities sought to prevent illegal migration across the Mediterranean. The case of the ship “Exodus” was particularly symbolic. In 1947 the ship was rammed and entered outside the port of Haifa by the British, who then forced its passengers to return to Germany. Once arrived at the port of Hamburg, hundreds of passengers were forcibly taken from three British transport ships and distributed to three facilities in Hamburg and the surrounding area, including the strictly guarded and hermetically closed off camp at Pöppendorf near Lübeck. Worldwide protests eventually persuaded the British government to terminate its Mandate over Palestine.

Commemorative plaque remembering passengers of the “Exodus” in Hamburg-St. Pauli,

Landungsbrücken

Source: Wikimedia Commons, photo: Ajepbah, CC BY-SA

3.0.

In 1947 the Jewish congregation in Hamburg had 1,268 members; in 1952 there were 1,044. Until the 1980s membership constantly remained at 1,000 to 1,500 individuals. However, these numbers conceal a high amount of fluctuation. New arrivals came in small groups from Hungary and eastern Europe as well as from Iran, which was unique to Hamburg. In addition to immigration there also was steady emigration of congregation members leaving mainly for Israel and the United States.

Before migration from the Soviet Union and its successor states began in the early 1990s, Hamburg was home to the fifth largest Jewish community in the former Federal Republic. German unification in 1990 meant fundamental changes for Jewish communities in Germany. In January 1991, the Conference of the State Ministers of the Interior Konferenz der Innenminister der Bundesländer adopted a decision made by the last government of the GDR according to which Jews from the Soviet Union were admitted to the country as so-called quota refugees [Kontingentflüchtlinge]. The term quota refers to the distribution of refugees to the various federal states. The decision remained in effect after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and now applied to it successor states as well. The considerable growth of Hamburg’s Jewish congregation was a direct consequence of this migration. From 1,390 members in 1989 the Jewish congregation grew to more than 5,000 in 2004. In 2004, 2,000 members of this congregation lived in Schleswig-Holstein, where there was no Jewish population to speak of prior to 1990. The Hamburg congregation thus supported the establishment of new congregations such as the one in Lübeck, for example. In 2005 the federal government introduced stricter legislation regulating the immigration of Jewish quota refugees and ethnic German resettlers [Spätaussiedler] from the former Soviet Union, as a result of which the number of migrants decreased significantly.

This text is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the work is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute the material in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Tobias Brinkmann (Thematic Focus: Migration), Dr. phil., is Malvin and Lea Bank Associate Professor of Jewish Studies and History in the Department of History at Penn State University. His research interests focus on the history of migration, especially Jewish migration from Central and Eastern Europe to North America.

Tobias Brinkmann, Migration (translated by Insa Kummer), in: Key Documents of German-Jewish History, 22.09.2016. <https://dx.doi.org/10.23691/jgo:article-219.en.v1> [February 26, 2026].