Jewish memory in the National Socialist period and the treatment of archival material after 1945

Memory and remembrance in mainstream society

The focus on victims in the culture of remembrance

The remembrance of victims in Hamburg

Postwar remembrance in Hamburg’s Jewish community

Official Forms of remembrance in Hamburg

The dualisms “remember – forget,” “memory – identity,” and “memory – remembrance” are a recent phenomenon, for in previous centuries people “forgot” what was no longer relevant or opportune. By contrast, we today believe the saying that “Those who do not know where they come from do not know where they are going.” While a personalized form of remembrance honoring idols or meant to create them in the first place prevailed during the Kaiserreich and the Weimar Republic, this first underwent a change in the Weimar period and particularly after the end of the Second World War. After the Shoah the “honoring of heroes” [Heldenverehrung] (understood in the sense of an idol) was replaced by the remembrance of victims. This mainly applies to the culture of remembrance prevalent in mainstream society, but the Jewish minority also remembers the murder of the Jews in various ways. Additionally, they have always preserved their history in religious tradition. Their community remembers and commemorates both as part of their religious practice and as part of society as a whole.

Memory has always been both public and private. Private memory takes its lead less from historic turning points, but from different phases in one’s own life such as birth, schooling, marriage, reaching adulthood or the loss of close relatives. If events such as war, starvation, economic crisis or persecution – or positive – events such as an economic boom change the life of an individual, however, chronological markers can coincide. Private memory usually remains outside of the public realm. Only in some cases does it become public and thus part of the culture of remembrance, through published family chronicles or diaries, for example.

Judaism knows many holidays and commemoration days keeping the memory of its people’s history alive, although their content and form changed over the millennia: Passover refers to the Jews’ exodus from Egypt, meaning the end of their enslavement; Sukkot or the Feast of Booths (sometimes translated as “Feast of Tabernacles”) actually began as a harvest festival and later changed into a commemoration of the period during which the Jews were wandering in the desert after their Babylonian exile; Hanukkah, the Festival of Lights, celebrates the rededication of the Temple while Purim commemorates the saving of the Jewish people from Persian minister Haman (356 BCE), who planned to eliminate them.

The five days of fasting and mourning, asking for contrition and repentance, also have a historical background, for each one of them stands for a calamitous event such as a siege, defeat or expulsion. While they originated as “national days of mourning” commemorating the destruction of the Temple, local customs often attached to them. In Hamburg during the Weimar period, for example, a day of fasting to commemorate the so-called “Henkeltöpfchen-Tumult” was established: it referred to anti-Jewish riots caused by a broken pitcher breaking out on August 26, 1730, an event barely present in either Jewish or non-Jewish memory today. In 1940 leading Jewish representatives of the association Reich Association of the Jews in Germany Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland attempted to declare October 22 a nationwide day of fasting in order to commemorate the deportation of Jews from the region of Baden on that day, which was prohibited by the National Socialist regime. A year later Hamburg’s Chief Rabbi Joseph Carlebach declared a regional day of fasting to commemorate the first deportations of Jews from Hamburg, which was not prevented. Today the Israeli commemoration day Yom HaShoa, which commemorates the victims of the National Socialist murder of Jews and Jewish resistance fighters, is observed by parts of both the Jewish and non-Jewish population in Germany as well.

In addition there are traditional forms of remembrance such as the week-long period of sitting shiva after a death in the family, funerals, and remembering the dead by the observation of Yahrzeit (also practiced in Christianity), meaning the ritualized remembering of the dead on the anniversary of their death. One peculiar feature in Jewish genealogy is the linking of family history with the history of the Jewish people. Families such as the Sephardic Shealtiels embed their history in the millennia-old history of the people of Israel, simultaneously maintaining family tradition and closeness although their family members are dispersed all over the globe. Meanwhile other families confine themselves to collecting stories, photos, family registers, and heirlooms in order to preserve the knowledge of people, events, and developments in family memory at least for a few generations.

One of the oldest Jewish commemorative traditions surviving to the present day regardless of majority society’s changing forms of government are Memorbücher. They record the names of congregation members who died a violent death due to their religion, be it in pogroms, crusades or in the Holocaust. They often also contain descriptions of the events leading to their fate. In her preface to a book commemorating the Jews of Schleswig-Holstein who were murdered in the Holocaust, Miriam Gillis-Carlebach refers back to the first known Memorbuch compiled in Nuremberg in 1296, for example.

Both privately and as a community, Jews observed their own occasions for remembrance and commemoration through traditions which in some cases were long-lived. However, they also participated and continue to participate in the commemoration days observed by mainstream society by joining rallies or writing articles among other things, and they continue to make their own mark on them. This was true for the SedanfeiernDay of remembrance for the defeat of the French army in the Franco-Prussian War 1870 during the Kaiserreich, the introduction of Mother’s Day in 1928, the 1930 celebrations of the “liberation” of the Rhineland, and the erection of memorials for Jewish soldiers who had fought in the First World War. In the Weimar period the Volkstrauertag (“Heldengedenktag”) in particular offered an occasion to remember the Jews who had died in the war. Even after the National Socialist takeover and until the mid-1930s, it served as an occasion to point out the Jewish community’s contribution and sacrifices during the First World War in speeches delivered at specifically Jewish “Heldengedenkfeiern.”

Jews in Hamburg and elsewhere honor the memory of prominent persons (mostly men) from among their ranks in laudations or articles on the occasion of a person’s passing or its anniversary. Another aspect of Jewish memory (hardly different from Christian habits) consists in the celebration of anniversaries of foundations, associations or institutions, which provide an opportunity to highlight developments and honor achievements.

After 1933 the National Socialist state banished all signs of Jewish life not only from Hamburg’s urban topography and social awareness. The Jewish community again reacted with a look back at its history. In light of the National Socialists’ increasingly extensive measures to eliminate all positive / honoring memory of Jewish existence, the Jewish community desperately sought to maintain, preserve, and safeguard it. Founded in 1905, the “Gesamtarchiv der Juden in Deutschland,” as the archive had to call itself as of 1935, collected the files of congregations, associations, and foundations as well as registers of births, deaths, and cemeteries and Memorbücher at its Berlin location. Beginning in the mid-1930s its director, Jacob Jacobsohn, urged Jews to give genealogical documents and mappahs, photos of sacral buildings or ritual objects, etc., in short: anything telling the story of centuries of Jewish life in Germany to the Gesamtarchiv in Berlin, which he still assumed safe. The Gestapo confiscated all its material in 1938, and the genealogical papers were sent to the Reichsstelle für Sippenforschung (later renamed Reichssippenamt), where they were used to confirm people’s “Aryan” origin. Meanwhile Hamburg’s Jewish congregation had refused to send its papers to Berlin for safekeeping and instead continued to run its own archive. Thus files documenting 400 years of Jewish life survived National Socialism and the war. After the war the precursor to today’s Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People in Jerusalem demanded the files be sent to Jerusalem since it considered them part of Jewish history. A lawsuit lasting several years ended in 1959 with a settlement according to which part of the files would remain in Hamburg’s State Archive Staatsarchiv and part of them would be given to the Jerusalem archive while copies of each part would be available in both places. The Institute for the History of the German Jews Institut für die Geschichte der deutschen Juden was founded by the city of Hamburg in 1964 to study these documents, and it opened its doors in 1966.

The culture of remembrance has become more diverse in recent years: it manifests itself in urban topography, in the media, and in collective and private memory. More specifically this means: statues and architectural monuments, the naming of streets, squares and buildings, memorials, memorial walls or plates, traveling and open air exhibits, public readings, decentralized plaques mounted on houses or stumbling stones Stolpersteine embedded in the pavement, books, online articles, and events, the reading out of names, marches, and lots more. More traditional forms of remembrance such as ceremonies featuring speeches and music continue to exist and are either complemented or replaced by new ones.

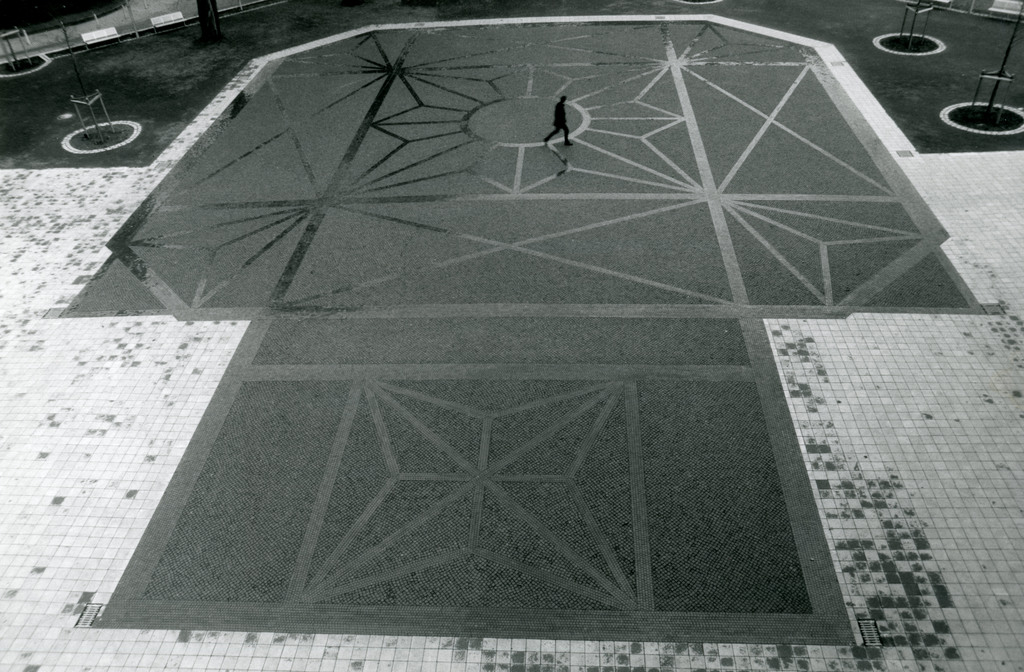

The mosaic visualizes the outline of the former synagoge at Bornplatz (today:

Joseph-Carlebach-Platz)

Source: Picture

Database of the Institute for the History of the German Jews, NEU00023,

photo: Margit Kahl, probably 1988, © 2017 Forum for the Estates of

Artists, Hamburg.

Traditionally it is deserving persons or important events of the past which are remembered because they are considered relevant to the present and essential to the shaping of the future, either because they imply an as yet to be realized “surplus” (Bloch) such as civil liberties or because they remember an injustice which must not be forgotten or repeated. In authoritarian regimes or dictatorships memory is steered from above, and all undesirable or nonconforming traces of earlier cultures of remembrance are either reinterpreted or eliminated. In democracies such as the Weimar Republic, the Federal Republic or the current Berlin Republic the processes of remembrance are more pluralistic, sometimes anarchic and unsynchronized, and they are initiated at both the government and the grassroots level. The form which remembrance takes in the public space is negotiated between its initiators and government actors such as politicians or those in charge of government offices and ministries.

As previously mentioned, the memory of individuals, their communities, and society at large is subject to constant change. It becomes modernized, parts of it fade while others become more important. New forms of government and society create their own ideals, idols, and occasions for commemoration. While commemoration ceremonies can be conceived of and celebrated differently, for architectural monuments a change usually means renovation, addition, relocation or even their destruction. In some cases they simply disappear, as an inventory of cultural monuments in Schleswig-Holstein has recently shown. 3,000 out of 16,000 such monuments no longer exist Nach Denkmalschutz-Reform. Erfassung von Denkmälern in SH [Schleswig-Holstein]: Viele sind verschwunden, in: shz.de, last access 6/4/2015. in that state because they have been demolished, built over or repurposed without the authorities noticing it or any kind of protest against it.

The “hero worship” [Heldenverehrung] of the 18th and 19th centuries – be it for wartime glory, political, scientific, artistic or other achievements or for the successful campaigning for emancipation and civil liberties – has become a thing of the past not only in Germany’s culture of remembrance. After 1945 it was essentially replaced by the remembrance of victims in the broadest sense, i. e. the focus gradually shifted to “the historic injuries people suffered and which were caused by other people.” Martin Sabrow, Held und Opfer. Zum Subjektwandel deutscher Vergangenheitsverständigungen im 20. Jahrhundert, in: Margrit Fröhlich (ed.), Das Unbehagen an der Erinnerung. Wandlungsprozesse im Gedenken an den Holocaust, Frankfurt am Main, 2012, pp. 37–54, here: p. 42. One effect of this change in values was a rapid rise in the number of monuments in the broadest sense. Another was that they are no longer to be found exclusively in central locations in the city, but often also in decentralized ones. In light of the uniqueness of the Holocaust, this “triumph of the victim’s perspective” Ulrike Jureit / Christian Schneider, Gefühlte Opfer. Illusion der Vergangenheitsbewältigung, Stuttgart, 2010, p. 10. has come to largely dominate mainstream society’s remembrance of the Jews’ work, lives, and suffering. Today the Holocaust as a historical event is universally considered a Europe-wide space of remembrance [“europäischer Gedächtnisort”], which is given a national and regional character in each individual place. The victim’s perspective is not limited to the victims of persecution, but it extends far into the ranks of perpetrators, so that in some cases murdered Jews are mentioned in the same breath as fallen soldiers of the Second World War or the victims of Allied air raids as “victims of war and tyranny.” According to its critics, the focus on victims is not just a sign of a change in values, but it also relieves members of mainstream society of ambivalent memories and implicitly offers to include later generations. There was a long-running debate about whether a central monument for the murdered Jews of Europe should be built in Germany. Once it had been realized, central monuments for other victim groups followed, and – in reaction to its location in the capital and its impersonal form of remembrance – it was eventually complemented by decentralized memorials such as stumbling stones Stolpersteine for individuals, which add names and fates to the number of victims (or create a contrast between these).

In Hamburg, too, monuments testify to a shift in priorities regarding the culture of remembrance. The destroyed and rebuilt monument to Heinrich Heine is a case in point. Today it shows a pensive Heine, and explanatory texts refer to the burning of books in 1935 and the destruction of the first Heine statue. In many cases artistic additions express the change in society’s values, as is the case with the war memorial Kriegerdenkmal at Dammtor train station. The city commissioned artist Alfred Hrdlicka to add two more monuments to it, which commemorate the 1943 firebombing of Hamburg and the mass deaths of Neuengamme concentration camp prisoners in the bay of Neustadt during Allied bombardment in 1945. Most streets and squares that had been named for Jews mostly in the Weimar period have been returned to these names, identifying their eponyms as significant musicians, architects, bankers or statesmen. Other than that, the “hero” has largely fallen out of fashion. Meanwhile the new culture of remembering victims is subject to constant change and certain trends as well: while numerous events were held to remember the persecution and murder of Jews in the second half of the 1940s, their number declined in the 1950s until it rose again in the 1980s.

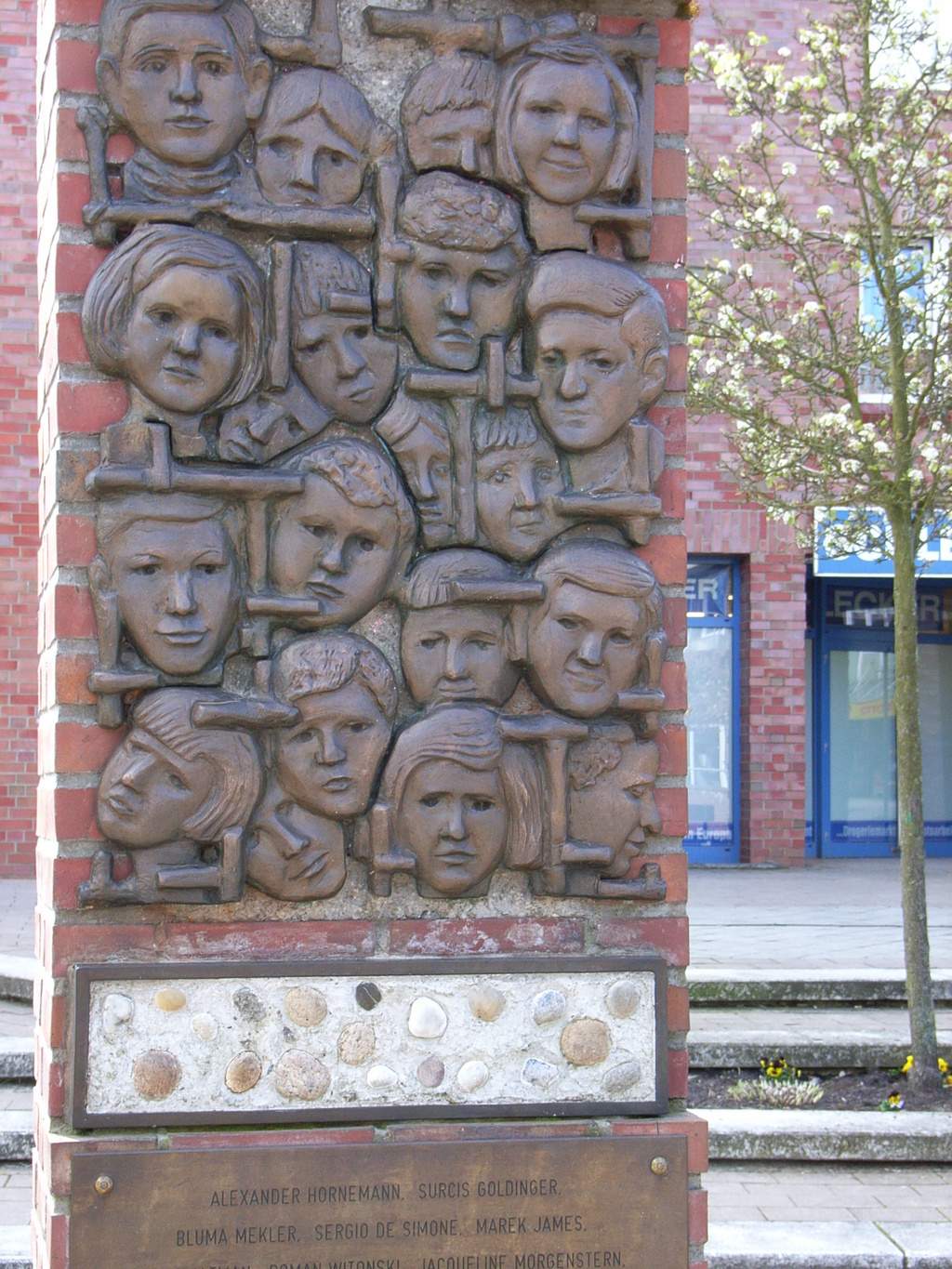

Hamburg’s Jewish congregation re-established in 1945 developed a culture of remembrance that both linked back to the Weimar period by honoring deserving Jewish personalities such as Joseph Carlebach (centennial), Gabriel Riesser (bicentennial) or those who had recently passed like Rav Gotthold (died February 15, 2009) and also celebrated the anniversaries of Jewish organizations in detailed accounts of their founding and history (such as the centennial of the Jewish cemetery at Ohlsdorf). In addition, three annual days of commemoration were established which are still observed to this day: the anniversary of the November pogrom of 1938, a bus trip to Bergen-Belsen including participation in a ceremony commemorating the liberation of this concentration camp, and Yom HaShoa remembering the murdered Jewish victims. For several years congregation members and representatives used to travel to Neustadt, where prisoners from the Neuengamme concentration camp had perished in the bay of Lübeck on board the Cap Arcona and other ships. They also held an event at the school on Bullenhuser Damm to remember the Jewish children who had been murdered in April 1945. The congregation’s work to remember the Shoah was “not meant to open up old wounds, but to prevent forgetting.” Walter L. Arie Sternheim-Goral, Festschrift zum 25. Jahrestag der Einweihung der Synagoge in Hamburg, 1960–1985, Hamburg [1985], p. 18..

Memorial in Hamburg-Schnelsen for the children of Bullenhuser Damm

Source:

Wikimedia Commons, photo: Holgerjan, public domain.

The congregation was actively involved in the creation of memorials in Schleswig-Holstein, including a commemorative plaque at the former synagogue in Friedrichstadt, an exhibition on Jewish life in Elmshorn at the local cemetery hall, and the restoration of the former synagogue at Rendsburg. At Hamburg’s Talmud Torah School, it mounted an inscription above the portal and a commemorative plaque inside the building. Since the 1980s the congregation has also been a voice in the debate about forms of remembrance in the city by criticizing the memorial at Moorweide, which did not include any information on the deportations (today there are explanatory displays), by demanding some kind of memorial for the destroyed main synagogue at Bornplatz (an artwork based on its floor plan was dedicated in 1988), and by praising the well-received sculpture in front of the former Temple at Oberstraße.

In the 1980s the number of celebrations increased and references changed. In their work with children and youths, educators now included remembering eastern European Jewry as “the former center of Judaism,” and new days of commemoration were added: one celebrating the founding of the state of Israel and a day remembering fallen Israeli soldiers (Yom Hazikaron). Beginning in 2000, the immigration of Jews from the former Soviet Union to Germany resulted in another change in the congregation’s culture of remembrance. There now are annual veteran’s celebrations during which Jewish former Red Army soldiers in cooperation with the Russian and Ukrainian consulates, the German War Graves Commission Kriegsgräberfürsorge, and the Association of Ghetto Survivors Verein der Ghetto-Überlebenden commemorate the defeat of National Socialist Germany. The congregation also opened up to remembrance, commemoration, and projects initiated by the non-Jewish public, announcements for which could be published in the congregation’s newsletter. These included the “march of the Living” held in Poland to commemorate the end of the war, the “Train of Remembrance” Zug der Erinnerung bringing an exhibition on the fates of deported Jewish children to Hamburg, and a conference titled “Inszenierung der Erinnerung” organized by the academies of Germany’s two Christian Churches. Conversely non-Jewish patrons take part in events honoring congregation members such as Arie Goral or Flora and Rudi Neumann who are held in high esteem outside of the Jewish community as well.

In the official city remembrance also initially focused on the time period up to 1938 (the first commemoration was held in 1948). Where victims who had died in a concentration camp were remembered, inscriptions did not identify those murdered as Jews. While an “Urn of the Unknown Concentration Camp Inmate” Urne des unbekannten Konzentrationärs from Auschwitz was installed in 1945 and integrated into a stele with other urns, only few memorials were built until the 1960s, few of which actually remembered Jews and most of them located in cemeteries. Since 1965 the Hamburg senate has regularly invited Jewish individuals who emigrated from Hamburg (yet it only started including Jewish and non-Jewish forced laborers in 2000). In the mid-1980s, when mayor Klaus von Dohnany declared “It is time for the whole truth” “Es ist Zeit für die ganze Wahrheit” (1984), a rapid rise in activities to remember and commemorate occurred as well as a change in their thematic focus. For historiography, too, had long avoided the Holocaust, and now, initiated by non-university researchers and groups and the newly established Geschichtswerkstätten, a debate about whether Hamburg had been a “Mustergau” during National Socialism or rather an oasis largely untainted by it unfolded.

Subsequent research initially focused on the “forgotten victims” before turning to the murder of Jews. Now attention was paid to individuals who had been victimized and events taking place in specific parts of the city. This resulted in new memorials and forms of remembrance such as walking tours informing about Jewish life and the persecution of Jews in those parts of the city which had not been among Hamburg’s main Jewish neighborhoods. They also remembered the life and suffering of unknown persons. The culture of remembrance now gradually began to include the Holocaust, eventually placing it at the center of remembrance. It also became increasingly diverse and international. Events commemorating the November pogrom are still being held today, but they have changed in character: instead of solemn speeches being given in a hall, the Grindel neighborhood is illuminated by thousands of candles placed on the stumbling stones Stolpersteine remembering the Jews murdered in the Holocaust, and vigils and academic symposia are being held.

Square of the deported Jews

Source: photo: Beate Meyer, 2006.

In the 1980s Hamburg’s Authority for the protection of historic landmarks Denkmalschutzamt launched a program of installing commemorative plaques: more than 40 of these were mounted on the walls of buildings of significance to the city’s history (blue plaques), the history of persecution and resistance (black plaques), and sites of Jewish life (bronze plaques). Further commemorative plaques were installed and financed by local and private initiative, most recently by art collector Peter Hess, who commemorates Jewish visual artists who had been expelled or murdered. Two plaques mounted on the Landungsbrücken bridges dedicated to the refugee ships “St. Louis” and “Exodus” point out international involvements. In 1939 the first of these ships was not allowed to disembark the 900 Jewish refugees on board in Cuba as promised, but instead had to take them back to Europe. The Jewish DPs on board the “Exodus” hoping to land in Palestine in 1947 also were forcibly returned.

In the mid- and late 1980s, memorial stones at “Platz der Deportierten” in Altona created by artist Sol LeWit (complemented by an explanatory plaque since the 1990s), a memorial stone remembering the Polish Jews deported in 1938, and the memorial in the gatehouse of the former concentration camp at Fuhlsbüttel were dedicated, to name just a few examples. New monuments and memorials are being erected to the present day, including a 2015 monument for the Kindertransporte of 1938 / 39 departing from the Dammtor train station, which remembers the roughly 1,000 lives of Jewish children from Hamburg saved by Great Britain.

An exhibit complementing the memorial at the Neuengamme concentration camp, where vast numbers of mostly foreign Jewish and non-Jewish prisoners were held as forced laborers and died, was opened only after years of campaigning (mainly by prisoners’ associations) in 1981, followed by memorial stones and memorials at its satellite camps. However, there still was a long way to go until the present memorial site could be opened in 2005, and it will take even longer for the almost forgotten train station Hannoverscher Bahnhof, from where Hamburg’s Jews, Sinti, and Roma were deported, to be made into the Lohseplatz memorial.

In contrast to these central memorials, the more than 5,000 stumbling stones Stolpersteine (as of 2016) evoke decentralized remembrance in everyday spaces. Art collector Peter Hess was responsible for bringing this campaign by Cologne artist Gunter Demnig to Hamburg. Financed by a “grassroots” effort, the stumbling stones Stolpersteine enable forms of remembrance ranging from a brief silence to a solemn occasion or an annual small ceremony. The biographical research that is part of the campaign makes it possible to give visibility to individuals in the mass of victims.

Laying of the 5.000th stumbling stone Stolperstein for Bela

Feldheim on March 29,

2016

Source: photo: Beate Meyer, 2016.

The web portal www.gedenkstaetten-in-hamburg.de describing more than 100 monuments and memorials as well as ten educational sites featuring exhibits serves as a guide to existing sites of remembrance and commemoration in Hamburg. Out of the changed culture of remembrance and the focus on the Holocaust grew a strengthened awareness of the sites of persecution and their history. Yet it also resulted in efforts to preserve the remnants of the city’s Jewish legacy without denying the significance of the Holocaust. This includes recovering existing monuments of Jewish life as well as creating a sense for the “empty spaces” resulting from National Socialist destruction or postwar urban planning. The virtual reconstruction of Jewish sites developed over the past 20 years, such as the three-dimensional computer visualization of the synagogue at Bornplatz (in the film “Shalom Hamburg”) offers new possibilities in this regard. The efforts to preserve Jewish heritage combine regional and international aspects, as illustrated by studies of Jewish cemeteries or the stages of Jewish migration long before 1933 or 1945.

This text is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the work is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute the material in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Beate Meyer (Thematic Focus: Memory and Remembrance), Dr. phil., is a Research Associate at the Institute for the History of the German Jews (IGdJ). Her research interests are focused on aspects of German-Jewish history, National Socialism, oral history, gender history and cultures of memory.

Beate Meyer, Memory and Remembrance (translated by Insa Kummer), in: Key Documents of German-Jewish History, 22.09.2016. <https://dx.doi.org/10.23691/jgo:article-221.en.v1> [February 17, 2026].