Jewish culture reflects the experience of Hamburg’s Jewish population. Jews might be the creators, sponsors or the audience of a given cultural product. It is often difficult to clearly separate Jewish culture from Christian culture. For example, the richly ornamented graves at the cemetery of the Portuguese-Jewish community make reference to Jewish tradition yet they often also include elements of Christian iconography. Since there was no Jewish printer in 17th century Hamburg, both Jewish printers in the Netherlands and Christian ones in Hamburg received commissions from members of the Sephardic community. In synagogue architecture, too, Jewish as well as non-Jewish elements are discernible. While Hamburg’s very active lodges were eager to promote Jewish culture, they did so in a bourgeois context. The cooperation of mostly Jewish scholars in the so-called Warburg circle was mainly devoted to an explicitly Christian school of art history. Finally, discussing and spreading Jewish culture, not necessarily involving Jewish participation, has been part of life in Hamburg and other major German cities since the 1980s.

Arts and culture are generally believed to be connected. According to this notion, a painting by Rothko and a recording of Schönberg are part of the entirety of 20th century intellectual, artistic, and creative achievements. Historiography has relativized this idea for some time, however. Our understanding of the term “culture” has been expanded to include “the ordinary.” Today historians no longer exclusively focus on the True, the Beautiful or the Good, but instead, in truly democratic fashion, consider all of human life a product of self-made patterns of meaning. Such an approach makes it difficult, however, to distinguish between the areas of science and education, leisure and sports or memorializing and memory (not to mention the arts). Thus the section titled Jewish Arts and Culture discusses topics which have long shaped the understanding of these fields – architecture, literature, music, and visual arts – as well their respective representatives, educators, and associations. These topics are therefore not analyzed for their expression of the True, the Beautiful or the Good, but instead are meant to shed light on Jewish life in Hamburg beyond a strained contrasting (elite vs. the masses, isolation vs. assimilation, and unity vs. dissolution).

While we depend on common conceptions of the term “culture” for pragmatic reasons, we have to do without them in other respects. For a long time it was considered a proven fact that Judaism was an aniconic religion. This led to the conclusion that Jews had an extremely ambivalent relationship to the arts. However, this view was based on the confusion of biblical text passages with a supposedly general expression of Jewish existence. First of all, there never was a general prohibition of visual creations for Jews, and secondly they were able to work freely in the arts after the Enlightenment. While it is relatively easy to identify Jewish art of the pre-emancipation period by means of certain motifs, this is not the case for subsequent centuries. A haystack painted by the Catholic Claude Monet refers to the same subject matter as a haystack painted by the Jew Camille Pissarro: the choice of subject matter says nothing about whether Pissarro’s work is Jewish. Does the painting nevertheless become a Jewish object because the artist was Jewish? This question, too, has to be answered in the negative. Jewish art reflects the experience of Jews in Hamburg as in other places in the broadest sense. In this process Jews may have been the creators, sponsors or the audience of a given work of art.

The history of Hamburg’s Jews begins at the end of the 16th century when Sephardic Jews expelled from the Iberian Peninsula fled to the city and were allowed to settle there. These so-called “Portuguese,” among whom there were successful bankers, physicians, and jewelers, maintained ties to other Sephardic communities in Europe and America. Many of them were laid to rest at the cemetery of the Portuguese-Jewish congregation. Today one can still look at the often richly ornamented tombs which testify to how Sephardic Jews wanted to see themselves: as participants of a rediscovered Jewish tradition (interrupted by their presumed conversion), as belonging to honorable professions, and as members of important families. The artful inscriptions in Hebrew, Portuguese, and Spanish document this rich history. At the same time, the stone ornaments depicting lions and crowns, angels and birds, skulls and hourglasses reveal something else: apart from biblical scenes referring to Jewish tradition, we often recognize references to Christian iconography (in the memento mori motif originating in Medieval monastic liturgy, for example) or to certain values held by their former Catholic homeland (such as personal honor or spirituality). The stone masons and sculptors who made the tomb stones were not Jewish. Thus the artwork one can admire at the cemetery is the product of various customs and conventions.

Biblical scenes on Sephardic tomb stones at the Jewish cemetery Königstraße in

Hamburg-Altona, Mary Fink

Source: Picture

Database of the Institute for the History of the German Jews, FRI00051,

originally from: Max Grunwald, Portugiesengräber auf deutscher Erde.

Beiträge zur Kultur- und Kunstgeschichte, Hamburg 1902, p. 31 and p. 62.

In the printing industry the situation is a similar one. In the 16th century, hundreds of books in Hebrew were printed, 17 of those in Hamburg, which made it one of the most important printing places in northern Europe. However, the authors of these books were Christian scholars of Hebrew. Between 1600 and 1638 a further 18 books were printed, among them the work of a Jewish writer, Binjamin Mussaphia. Since there were no Jewish printers in Hamburg in the 17th century, Jewish printers in the Netherlands as well as Christian ones in Hamburg received commissions from members of the Sephardic community wanting to publish collections of sermons or grammar books. It is no coincidence that the collaborations between Jewish scholars and Christian printers recall Medieval Jewish manuscripts whose richly ornamented illustrations incorporated Gothic visual elements such as the gold background or characteristic geometrical shapes. For these illustrations had often been the work of Christian miniature painters. There is one important difference between Jewish late Medieval or Early Modern illuminated books and later Jewish forms of art, however: while the former were recognizably Jewish due to their content, language, motifs or publisher, this was not necessarily true for later works.

Needless to say there was a direct Jewish context in synagogue architecture. At first Sephardic Jews made use of secret prayer halls since they sought to continue to hide their Jewish origins from Hamburg’s senate. It was not until 1771 that they built their own synagogue. Meanwhile, the neighboring Ashkenazi congregation of Altona had built their own house of prayer in 1682. Its arrangement of the Bimah, the Ark, and the pews all conformed to the traditions of both Sephardic and Ashkenazi congregations. As was customary in Europe, these buildings were located in courtyards to avoid “competition” with the Christian majority faith. A 1710 Hamburg law codified this deliberate invisibility of Jewish religiosity.

Congregations could not refer to a specific architectural style for their synagogues as none had ever existed. As in the case of printing, it was almost exclusively non-Jews who received commissions for their building. In the 19th century, when Hamburg became a center of Reform Judaism, architecture adapted to the new rite. In the New Israelite Temple Neuer Israelitischer Tempel, the Bimah was now located at the eastern wall, strongly reminiscent of a Protestant pulpit. A balcony for the organ and the choir was installed and there no longer was a mekhitza to separate the women’s balcony. In synagogue architecture, too, both Jewish and non-Jewish elements are discernible. Religious and ritual requirements such as the Ark to hold the Torah scrolls naturally remained while aesthetic preferences reflected contemporary tastes. As in the design of tombs, there was an interplay of Jewish interests, local building ordinances, and architectural movements. The Temple building was influenced by the English Gothic style and the Schinkel School; the synagogue belonging to the Jewish hospital am Wall took Renaissance and Romantic architecture as its models; the floor plan of the Kohlhöfe synagogue followed the example of Byzantine churches while its façade took inspiration from northern Italian architecture. In the 20th century, this interplay repeated itself, in some cases under different conditions: some of the designs influenced by Art Nouveau and Neues Bauen [New Architecture] were the work of Jewish architects such as Semmy Engel, Felix Ascher, and Robert Friedmann. In this context the only example of a development particular to Hamburg was the untimely decision to build the Synagogue at Neues Dammtor Neue Dammtor Synagoge at Bornplatz consecrated in 1895 in an oriental style. For in the rest of the country (with the exception of Cologne) congregations now spurned orientalizing elements in synagogue architecture thus hoping to invalidate the allegation that Jews did not belong in Germany. Whether Hamburg’s Jews felt safer than Jewish communities in the rest of Imperial Germany despite the existing antisemitism making “scientific” claims at the time cannot be deduced from such an anomaly, however.

The further integration into mainstream society progressed, the more difficult it is for contemporary historiography to define a decidedly Jewish art or culture. Jewish associations are an exception, however. Hamburg’s very active network of lodges was very eager to promote Jewish culture. In 1898 the Henry Jones-Lodge initiated the founding of the Society for Jewish Anthropology Gesellschaft für jüdische Volkskunde, whose museum, library, and archive the lodge soon housed. Lectures and exhibitions were meant to not only enrich Jewish cultural life, but also to represent a confident Jewry. We can assume similar motives for the founders of the Association of Jewish History and Culture Verein für jüdische Geschichte und Kultur. At the time, this national association counted 180 local chapters and about 15,000 members. In the face of increasing hostility towards Jews, strengthening Jewish self-regard was not the least of their concerns. Both the Society for Jewish Anthropology Gesellschaft für jüdische Volkskunde and the Association for Jewish History and Culture Verein für jüdische Geschichte und Kultur were part of a growing network of Jewish and non-Jewish associations. In Hamburg, too, multiplying interests within the various demographic groups resulted in experiments with new forms of organization.

In the “Third Reich” such experiments were a thing of the past. The National Socialists forced everything “in line” which was not compatible with their claim of undivided representative authority. When the regime excluded Jewish artists from the cultural industry, those affected by the professional ban reacted with the nationwide founding of the Cultural Association of German Jews Kulturbund deutscher Juden, which in 1935 was renamed “Jewish Cultural Association” Jüdischer Kulturbund by order of the authorities. The language used here shows that for most Jewish artists the year 1933 by no means marked the end of their German identity. Now unemployed, these singers, actors, musicians, and dancers were forced to look for new ways to earn a living. In May 1933, a Society of Jewish Artists Gemeinschaft Jüdischer Künstler was founded in Hamburg and later became the Jewish Society for Arts and Science Jüdische Gesellschaft für Kunst und Wissenschaft. From August 1935 until its closing in early 1939, this association was registered as Hamburg Jewish Cultural Association Jüdischer Kulturbund Hamburg. While it initially staged performances of classic works such as Lessing’s “Nathan the Wise,” Beethoven’s “Egmont Overture” or Schubert’s “Unfinished Symphony,” the Gestapo gradually prohibited them from performing works by “German” authors and composers. Nevertheless, those working in the arts who had not left Hamburg did not limit their activities to feature only supposedly Jewish art. Of all plays performed by the Jewish Cultural Association Jüdischer Kulturbund Hamburg, only a third had been written by Jews, and of these 27 plays by Jewish authors less than half dealt with an explicitly “Jewish” subject matter. This shows that their relationship to their German-Jewish or European-Jewish heritage remained complex despite all National Socialist chicanery.

Naturally Jews in Germany’s mainstream culture are part of Jewish culture around 1900, but not in the sense of a problematic contributionist history according to which Jews represent an “enrichment,” as if actual culture was by definition non-Jewish yet every now and then profited from Jewish ideas. Instead we should see this phenomenon in sociological terms in the sense that some Jews were sufficiently integrated and artistically ambitious enough to play a leading role in the cultural sphere. Only a few examples can be mentioned here. Baruch Pohl, who called himself Bernhard Pollini in Hamburg, was the director of three of the city’s major theaters (Stadttheater, Altonaer Theater, and Thalia Theater) in the 1890s. Members of the Hamburg Secession included prominent local artists such as Willy Davidsohn, Paul Henle, Alma del Banco, and Gretchen Wohlwill. In the Weimar Republic, the Stadttheater (Staatsoper as of 1934) was headed by Egon Pollak for a long time. Until 1926 actress Mirjam Horwitz and her non-Jewish husband Erich Ziegel were joint directors of the Kammerspiele Hamburg's intimate theater.

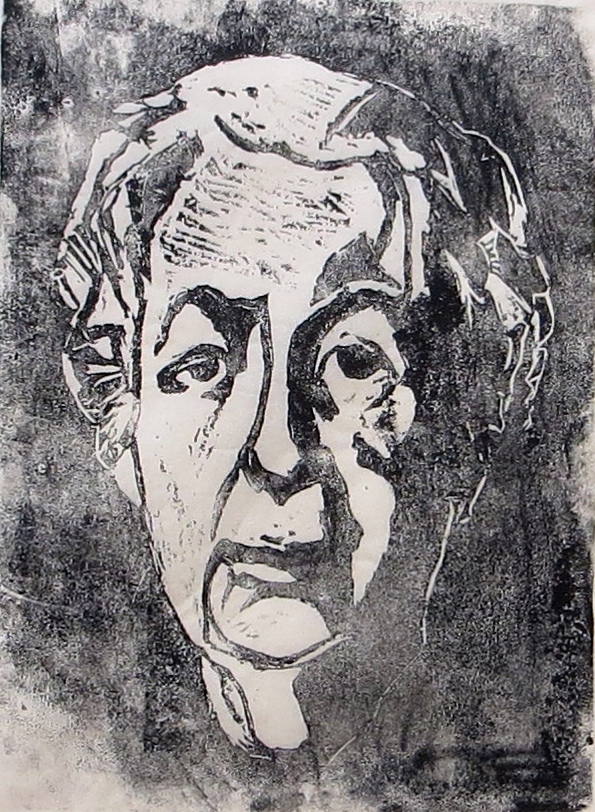

Gretchen Wohlwill,

„Self-portrait“, woodcut on paper, 18,5 cm x 25 cm, ca. 1940–1950

Source: With kind

permission of the Gallery „Der

Panther“.

After the Shoah, Ida Ehre was to become the theater’s principal and determine its course for decades.

Even if this list of names (to which many others could be added) cannot compete with the many famous names in Berlin’s cultural scene, it is remarkable how many Jews in prominent positions influenced Hamburg’s culture. Yet they did not do so – and here a reminder of Pissarro’s haystack is in order – as Jews or in the name of the Jewish people, at least not until National Socialist policy suggested to them to only act as Jews. Their works were reminiscent of Cézanne or Maillol. In their stage productions, they were influenced by Expressionism, New Objectivity or Existentialism. Their concerts and operas were dedicated to the classics or New Music. If the Jewish background of these artists played a role at all (and there are no verifiable causalities in this respect), then it was insofar as they promoted new art forms – as the large number of Jewish members of the Hamburg Secession suggests. As outsiders in a deeply Christian society (which often discriminated against minorities) they looked for opportunities to express their curiosity or their creative urge.

To this day the city of Hamburg is associated with the Warburg Library, or as it was originally called, Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg (KBW). In order to adequately honor the significance of this legacy, it may be more appropriate to speak of a Warburg circle or of the Hamburg School. Although this circle was not as influential as psychoanalysis or the “Frankfurt School,” it resembled them structurally: it was a collaboration of mostly Jewish scholars aiming to establish a new academic discipline or questioning existing thought by means of an interdisciplinary approach.

The Warburg circle is mostly associated with a new direction in art history. Aby Warburg understood it as an attempt to examine general semantic contexts independent of formal analytical criteria in order to reveal a kind of collective memory. Among the members of this circle also were scholars in other disciplines, most importantly Ernst Cassirer, whose philosophical oeuvre owes much to this intellectual environment. Fritz Saxl, who ran the library with Gertrud Bing for many years, gave accounts of Cassirer’s constant presence at the KBW. Without the collection built up by Warburg, which not only included academic literature on art history, but also works on alchemy, anthropology and psychology, Cassirer would have been unable to write the second volume of his “Philosophie der Symbolischen Formen” (Philosophy of Symbolic Forms) Ernst Cassirer, Philosophie der symbolischen Formen. Zweiter Teil: Das mythische Denken. Meiner Verlag, Hamburg 2010. . Erwin Panofsky, a tenured professor of art history at Hamburg’s relatively new university since 1926, closely cooperated with members of the circle: he adopted Warburg’s iconological method which examined the cultural significance of artworks; of Cassirer’s ideas he adopted that of “symbolic form” and applied it to questions of iconography. Panofsky was to become one of the 20th century’s most important art historians. Meanwhile Cassirer’s significance for modern philosophy is increasingly being acknowledged.

There are at least four elements which explain this cooperation in the context of Hamburg’s history: first, fate, fortune or coincidence. Second, Hamburg’s relatively underdeveloped arts sector, which had previously allowed Alfred Lichtwark to run the Kunsthalle without state interference and open it to innovative artistic styles or educational approaches. The relative absence of established structures, conservative forces or informal networks of influence benefitted all those wanting to venture in new directions. Third, the founding of a new university in the tradition of Jewish patronage, in which Warburg was involved. Fourth, the Warburg Library’s financial independence which rendered many things possible which were unthinkable elsewhere. Much of the above is reminiscent of the situation in Frankfurt am Main, where the Institute for Social Research Institut für Sozialforschung became as significant for sociology as the Hamburg circle did for art history.

Frankfurt was fortunate in that the city developed a fairly high level of intellectual life after the Holocaust due to the return of Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer to its university. It is important, however, not to understand the so-called “Frankfurt School” as synonymous with Jewish intellectual life, for in the postwar period most of the city’s Jews (and those living elsewhere) were engaged in matters other than questioning the “culture industry” or studying the “Dialectic of Enlightenment.”

With few exceptions, Jewish survivors wanted to leave Germany as quickly as possible. Before they were able to act on this plan, they made what they considered a “stopover” in the Western occupation zones. Culture certainly was important to the Displaced Persons (DPs) mostly hailing from eastern Europe. Amateur theater groups and professional ensembles such as the Kazet Theater at Bergen-Belsen and Munich’s Jiddisches Theater gave those living in the camps an opportunity to newly discover or rediscover Yiddish literature. Cabaret performances and recitals alternated with classic plays by Avrom Goldfaden and Scholem Aleichem. The performances dealt with the audience’s most recent experiences. This was meant to strengthen the historical awareness of those survivors who had not immediately experienced persecution and therefore were possibly less inclined to pursue the Zionist mission of emigrating from Germany to Palestine. For many Jews, culture after 1945 not only meant distraction and entertainment, but also opposition to a diaspora existence which was supposed to become a thing of the past.

Of the roughly 200,000 Jews living in various DP camps or large cities in the immediate postwar period, only 30,000 remained in the country and between 1,200 and 1,400 of them in Hamburg. Any attempt to compare “the surviving remnant” der “gerettete Rest” in Hamburg with what used to be Germany’s fourth largest Jewish community numbering almost 20,000 members would be inappropriate. As far as Jewish culture is concerned, the consequences of the National Socialist policy of extermination affected Hamburg to a relatively high degree: in contrast to Berlin, Frankfurt, Munich or Düsseldorf it never became a “center” of renewed Jewish life after 1945.

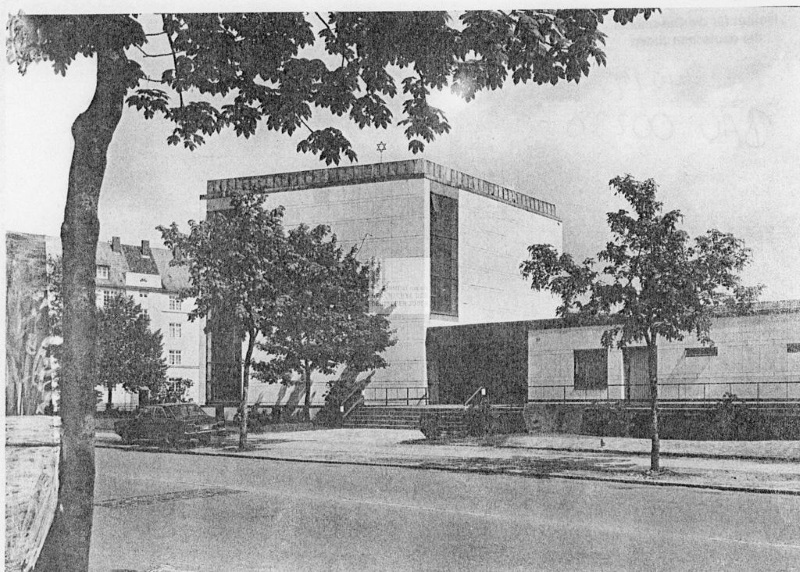

View on the synagogue Hohe Weide in Hamburg on the day

of its inauguration, September 4, 1960

Source: Picture Database of the Institute for the History of the

German Jews, BAU00231, photographer: Andres, Erich / Jewish Congregation

Hamburg, album 13.

The fact that we are discussing the rebuilding of its community shows that in Hamburg, too, Jewish life did not solely consist of worrying about one’s day to day survival. Synagogues were built as early as the 1950s in Stuttgart and Cologne, among other places. In September 1960, congregation members and Hamburg city representatives gathered for the dedication of the new synagogue in Eimsbüttel. The words spoken by Mayor Max Brauer on this occasion were quoted much later, on the occasion of the 1986 opening of a community center in Frankfurt: “Only those create a building dedicated to the service of the Highest who have the firm will to stay.” „Ein dem Dienst am Höchsten gewidmetes Bauwerk schafft nur, wer den festen Willen zum Bleiben hat.“, Michael Brenner, 1950: Neue Synagogen, in: Jüdische Allgemeine, 15.11.2012, http://www.juedische-allgemeine.de/article/view/id/14482 (4.4.2016).

Architect Klaus May, son of the much better known former Frankfurt building commissioner, Ernst May, and his assistant Karl Heinz Wrongel had been commissioned to design a modern building which was plain, functional and mostly unadorned. The only exceptions were the colorful windows designed by Hamburg painter Herbert Spangenberg and the exterior doors designed by Hamburg artist Traute Beermann. The ritual basin (mikveh) had been designed by Jewish Frankfurt architect Hermann Zvi Guttmann, who had previously been commissioned to design the interior of the synagogues in Düsseldorf and Offenbach. A cultural commission organized musical and literary events in the community hall attached to the synagogue, many of which reflected the Zionist spirit of the postwar period not only in Hamburg, but in the rest of Germany as well. At first Israel remained the central cultural reference for many of Hamburg’s Jews. Incidentally, the costs for the entire building were covered by the Office for Compensation and Restitution’s compensation fund.

Due to the small size of their community, the city’s Jews depended on non-Jews also being interested in Jewish culture. There rarely was agreement on what the latter consisted of, however. In the first decades of the postwar period, Hamburg’s non-Jewish citizens learned about the fate of Anne Frank or, as members of the Society for Christian-Jewish Cooperation Gesellschaft für christlich-jüdische Zusammenarbeit, co-founded by Ida Ehre, Harry Goldstein and Erich Lüth in 1952, attempted to understand Judaism as more than just an outdated “precursor” to Christianity. In 1953, a Working Group for the History of Jews in Hamburg Arbeitsgemeinschaft für die Geschichte der Juden in Hamburg led by historian Fritz Fischer was formed; thirteen years later, its efforts were to result in the founding of the Institute for the History of the German Jews Institut für die Geschichte der deutschen Juden which was the first research institute in Europe dedicated exclusively to the study of German-Jewish history. Israel and the Federal Republic established diplomatic relations in 1965, and ten years later a German-Israeli Society Deutsch-Israelische Gesellschaft was founded whose members were eager to promote cultural exchange between the two countries. Artists from Israel as well as artists whose work dealt with Israel were given opportunities to exhibit their work in Hamburg. The society continues to invite artists to Hamburg to this day, often in cooperation with the Society for Christian-Jewish Cooperation and the Liberal Jewish Congregation.

It was not until the 1970s that the policy of “compensation and restitution” [Wiedergutmachung] developed into what might be called a broad interest in “Jewish culture.” This curiosity often referred to an imagined Judaism which for some became an idealized place to yearn for. The musical Anatevka is a good example for this. Four years after its 1964 New York premiere, the Operettenhaus Hamburg staged a production of this work which portrays the Shtetl-romanticism of eastern Jews in pre-revolutionary Russia. Apart from Israeli actor Shmuel Rodensky, it was Ivan Rebroff in particular, playing the role of milkman Tevje, who rose to great popularity in the Federal Republic.

The non-Jewish audience’s interest mostly arose out of a feeling of historic responsibility, however. The German Film Ratings Agency’s wording of its rating for the 1989 film “Der Rosengarten” [“The Rose Garden”], which was in part shot in Hamburg and tells the story of the medical experiments carried out on Jewish children during the National Socialist regime, is a reminder of this. Only a short time later, nostalgia or responsibility were to become less important for the consumption of Jewish culture. A new, postmodern attitude towards life allowed many people to combine bagels and Jewish salons, menorahs for Hanukkah and klezmer music, Manishewitz wine and Woody Allen in a way that resulted in something Jewish—at least in their minds. Today the discussion and reproduction of Jewish culture – which does not necessarily require Jewish participation – features prominently in many major German cities. In the case of Hamburg, Jews and non-Jews benefit from various cultural offerings in the Grindel quarter, for example at Café Leonar, which hosts readings and a regular Jewish salon.

In this sense, the concept of culture preferred by historiography can again be applied. According to it, Jewish arts and culture should not just be associated with the intellectual and creative achievements of Jewish individuals or Jewish associations (of which very few exist in Hamburg today), but also with those patterns of meaning both Jews and non-Jews exhibit every time they believe to be producing or reproducing Jewish culture. The immigration of tens of thousands of Jews from the former Soviet Union supports this new diversity as well. A religious definition of Judaism is alien to many Russian or Ukrainian Jews, so that they are much less familiar with synagogue architecture than some “long-established” members of the community, for example. Their ideas of Jewish art grew out of their experience in a different culture (and language) where Judaism was defined ethnically. In other words, those who listen to a reading at Café Leonar today are approaching the subject with an entirely different knowledge than those who attended cultural events organized by the Jewish congregation only thirty years ago.

This text is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the work is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute the material in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Anthony D. Kauders (Thematic Focus: Arts and Culture), Dr. phil., is Deputy Director of history at Keele University and Professor for Modern European History. He is currently doing research on the history of hypnosis, social psychology and psychotherapy.

Anthony D. Kauders, Arts and Culture (translated by Insa Kummer), in: Key Documents of German-Jewish History, 22.09.2016. <https://dx.doi.org/10.23691/jgo:article-214.en.v1> [February 23, 2026].