“The history of German Jews […] can no longer be written without focusing on the different living conditions of women and men.”

Looking at historical and contemporary women’s biographies and the work of women in various fields opens up new perspectives on Jewish history. The widespread stereotypical perception of Jews in the public sphere as exclusively Orthodox and male not only contradicts social reality, it also fails to recognize the important role of women in politics, society and the economy, culture or family. Moreover, it obscures the diversity of Jewish life, which also finds its expression in a multitude of female role models.

Our seventh online exhibition looks at Jewish women as actors in their respective fields of activity: in the family and at a medical congress, at school and in court, or at the theater and a shipping company. Using ego documents, this exhibit highlights exemplary women’s biographies and their historical significance. Unavoidably, many important women are omitted, and not all chapters can cover the entire period of Jewish life in Hamburg and its varying historical conditions. Finally, it should be pointed out that the limited availability of surviving female self-testimonies compared to men’s history imposes an additional limitation, reflecting both the women’s historically lower access to education and traditional role attributions. In order to depict the present as well, additional interviews were conducted with representatives of Jewish life in Hamburg. How the protagonists themselves define their “Jewishness” varies from person to person and based on their social framework, ranging from traditional-religious to Zionist or bourgeois-liberal to “Jewish” as a foreign attribution.

The five chapters (1. family and private life, 2. learning, teaching and research, 3. politics and society, 4. art and culture, 5. work) outline various areas of activity. They each depict about seven female actors in their work, proceeding roughly chronologically. Thus they trace the development of the legal framework and the traditional gender roles and family images that shaped women’s professional and social opportunities.

“According to Jewish tradition the woman alone is in charge of the household, which primarily means keeping a kosher kitchen and planning for the religious holidays. […] Despite all the major changes that had occurred, most Jewish marriages were arranged well into the 19th century, and in Orthodox families this tradition continued even longer. The family ensures the passing on of the Jewish tradition.”

For the family life of Hamburg Jewish women in the Early Modern period, the history of everyday life beyond the records of prominent women such as Glikl of Hameln (1646–1724), who is presented here as a representative of many women, is thin on sources. Yet women were sometimes entrusted with business management in addition to raising children and managing the household in the absence of their husbands who were engaged in trade.

When Hamburg’s Jews were granted legal equality in 1861, this also created new opportunities for women, and Jewish welfare work was a traditionally female field of activity that continued to develop with the emergence of the bourgeois women’s movement. Modernity broke up conventional family structures, and at the same time the number of interdenominational marriages grew in the early 20th century.

The Nazi takeover destroyed Jewish and interdenominational families. The new Jewish (congregational) life that hesitantly emerged after the Shoah was given new facets by the influx of Persian Jews from 1950 and so-called Jewish contingent refugees from 1989.

This chapter provides exemplary insights into family networks (Betty Heine, Charlotte and Anna Embden, Jette bat Glückstadt), female educational paths (Sophie Magnus), women’s emancipation and child rearing (Johanna Goldschmidt), and the rescue of children during the Shoah (Eva Warburg). The special role women played in emigration is also highlighted (Steffi Wittenberg).

“Almost all your earlier poems have already been parodied by me, […] and only a Chimborazo of unmended stockings prevents me from becoming a blue namesake.” (Anna Embden)

Numerous letters, edited and digitally accessible in the Heinrich Heine Portal, testify to the lively correspondence between the women of the Heine family and their famous son, brother and uncle. In three selected letters from the years 1851 and 1854, which Heinrich’s mother Betty Heine (1771–1859, actually Peira, née van Geldern) as well as his sister Charlotte Embden (1800–1899), née Heine, and her daughter Anna (b. 1829) sent to the poet in his Paris exile, not only maternal care and advice to the son (cf. letter of November 11, 1851) are given. The affectionate support of Charlotte Embden for her brother also becomes obvious. She was in contact with his publisher, Julius Campe, represented her brother and, as mentioned in the letter of January 26, 1854, organized book shipments to Paris: “Hopefully you will have received the box, it is Campe’s fault that it left eight days later.” Embden received a liberal enlightenment education in the Heine family. In Hamburg, where she lived from the 1820s until her death, she brought together personalities of contemporary literature, art, and music as a salonière in the 1840s. Her daughter Anna also appears in the letter of November 12, 1854, as a self-confident young woman and correspondent who “parodied” her uncle’s poems and to whom reading them gave “the greatest intellectual pleasure.”

“Further, let my memorial candle burn for an entire year in the synagogue, also my gravestone shall be erected from the proceeds of my estate, and pay also for the costs of my funeral, […] including a coach in which four women shall escort my body.”

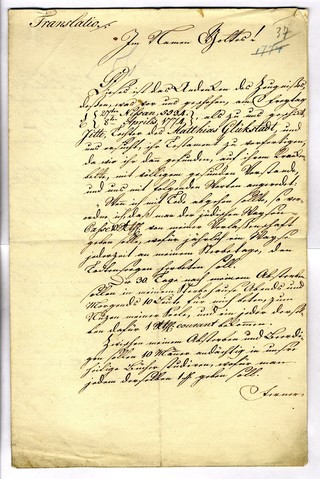

Jitte Glückstadt, an unmarried Jewish woman in Altona, had her last will and testament recorded on April 8, 1774. A testament (from the Latin testare, to testify or bear witness to) enables a person to arrange what is to happen to one’s personal property after death, as well as the details of the burial and funeral ritual. Jitte Glückstadt performed this act. Two men came to her sickbed, heard her dictate her last will, and recorded it. The extant testament is not the Hebrew or Yiddish original, but rather a translation into German. This is noteworthy because in the 18th century, High German had not yet developed into the everyday language of German Jews. After the death of Jitte Glückstadt on July 8, 1774 , the translation was prepared for non-Jewish officials so that non-Jewish residents of Altona could be informed as to the provisions Jitte had made. The testaments of Jewish women and men were translated and delivered to non-Jewish officials only if there were tangible grounds. Such grounds might be that debts were greater than the estate [could meet]. In this way, Jewish or non-Jewish creditors would be informed as to whether they would have to forego payment or if there was a sufficient estate with which to settle the debts. Read on >

“Our children are not there for us, we are there for them.”

In the summer of 1849, Hoffmann & Campe published a book entitled “Muttersorgen und Mutterfreuden. Worte der Liebe und des Ernstes über Kindheitspflege. Von einer Mutter. Mit einer Vorrede vom Seminardirector Diesterweg.“ [A Mother’s Cares and Joys. Words of Love and Seriousness about Childhood Care. From a mother. With a preface by Seminardirector Diesterweg.] The author was Johanna Goldschmidt from Hamburg, who presented her thoughts on child rearing in eleven chapters and a total of 220 pages. Her ideas were influenced by her personal experiences as a mother as well as by the movement of reform pedagogy. In his preface the well-known pedagogue Adolph Diesterweg praised the simple and clear style of the manuscript, writing that a “place of honor” should be given to the manuscript (Preface, p. XI). He subsequently began a correspondence with Johanna Goldschmidt. In their mutual exchange, the two deepened the discussion about ideas on early childhood education. In contrast to previous publications, Johanna Goldschmidt focused on the infant and thus on the early phase of the toddler, which had previously been neglected in educational considerations. Read on >

“Father also wanted mathematical instruction for us, but this failed because the only teacher suitable for this in Hamburg at that time, Mr. Lübsen, indignantly rejected the request to teach girls. So this good intention could not be carried out and I had to go through life without a concept of mathematics.”

In her childhood memoirs, written shortly before her death, Sophie Magnus (1840–1920), née Michaela Sophie Isler, describes growing up in an educated middle-class and socio-politically active parental home.

Influenced by her upbringing, after her marriage to the lawyer Otto Magnus (1836–1920), the Hamburg native became involved in improving the living conditions of socially disadvantaged groups at her new home in Braunschweig. In 1871, for example, she was involved in the founding of an educational association and initiated a child protection association. In 1888, she was also elected to the board of the newly founded Braunschweig “Mägdeherberge” (maids' hostel), which provided temporary accommodation for maids seeking work.

Sophie Magnus had a close relationship with her parents, Dr. Meyer Isler (1807–1888) and Emma Isler (1816–1886), née Meyer. From them she inherited the conviction that girls’ education should go beyond their role as future housewives and wives and produce independent personalities. Accordingly, they had invested in their daughter’s education, which began at age five in the private home of her parents with two employed elementary school teachers and a small group of girls. Sophie Magnus then attended a private girls’ school on ABC Strasse in Hamburg’s Neustadt district. Further private lessons followed, always also from her father, who taught her, among other things, natural history subjects and Latin – probably also because of the problems described in the above quotation.

“Sweden”

On six pages of a notepad, kindergarten teacher Eva Warburg wrote down the names of some of the children enrolled at the Jewish day care center at Jungfrauenthal 37 in Hamburg, which she ran, who were to be evacuated abroad in late 1938 in view of the increasing persecution of Jews. The page shown here is now in the archives of the central Israeli memorial site Yad Vashem. According to a handwritten reference in the same collection, her mother Anna Warburg also noted the children’s destinations on this list after her daughter had left for Sweden. […] The Jewish congregation in Stockholm [Mosaiska församlingen i Stockholm] had invited Eva Warburg to come to Sweden in September 1938. The aid committee appreciated her activities in child and youth work and Zionist refugee aid and hoped that Warburg would continue her work for the congregation in Sweden. Eva Warburg had Swedish language skills through her Swedish-born mother, the well-known pedagogue Anna Warburg. Her work in the children’s and youth aliyah in Sweden was to have a lasting legacy. Read on >

“At the moment when it really was about our survival, my mother […] showed more initiative.”

In December 1939, Steffi Wittenberg (née Hammerschlag, 1926–2015) and her mother managed to escape to Montevideo, Uruguay, where her father and brother had already emigrated in October 1938. Their rescue by emigration from Nazi Germany also meant a new beginning in unfamiliar surroundings, which presented the family – like most emigrant families – with various challenges. In this interview recorded in 1995 for the Workshop for Remembrance [Werkstatt der Erinnerung], Steffi and her husband Kurt Wittenberg recall that especially in the early days, women in emigration played a special role in the reorganization of everyday life and family life. Women were often younger than their husbands, and the traditional distribution of roles and their domestic responsibilities as mothers usually meant they found it easier to adapt.

Steffi Wittenberg lived in Uruguay for a total of eight years, where she also met her future husband Kurt. The young couple then lived in the U.S., where they campaigned against racism and quickly became targets of the McCarthy-era anti-communist smear campaign. After a lawsuit against the deportation proceedings initiated against both of them resulted in a settlement, they returned to Germany in 1951. The couple settled in Hamburg. Until her death in 2015, Steffi Wittenberg was one of the most committed contemporary eyewitnesses, for whom the memory of the Nazi era was a constant reminder to fight against injustice and inequity in the present.

For a long time, school education in Judaism was largely equated with religious education and almost exclusively reserved for the male world. This changed at the turn of the 19th century, when the ideas of the Enlightenment set off a comprehensive inner-Jewish process of secularization in which education and science became crucial. The strengthening of secular education changed the role of Jewish girls and women, which was no longer limited to the domestic sphere. Among the Jewish schools that sprang up as a result of compulsory education, adopted in 1860, were numerous institutions for girls.

When German universities finally opened their lecture halls to women around 1900, up to a third of the first female students were Jewish, a disproportionately large share. Many Jewish female students were particularly drawn to medicine, as the liberal professions promised better prospects than a career as a civil servant or employee. Rahel Liebeschütz-Plaut represents a young generation of committed Jewish women physicians at the beginning of the 20th century. School principal Mary Marcus devoted her life entirely to girls’ education. The biography of teacher Lilli Popper reflects the educational reform enthusiasm up to the early 1930s, coupled with a strong awareness of a Jewish identity and, ultimately, the break with an increasingly antisemitic Germany. Agathe Lasch, Hedwig Klein, Rosa Schapire and Gertrud Bing belonged to the first generation of female German humanities scholars and are representative of a brief intellectual heyday in Hamburg during the 1920s. The selected sources show the mood of social awakening in parts of the Jewish bourgeoisie, which also led to the roles of women and girls being rewritten. At the same time, they point to the rapid political development, depicted in the span of a lifetime: from social opening and emancipation to intellectual narrowing, dictatorship and antisemitic persecution. In the decades after 1945, the number of women in education and science increased rapidly. But it took a long time before Jewish life and education also became part of normal life in Hamburg. The video by Deborah Tal-Rüttger provides insights into the present circumstances of Jewish educational work.

Gertrud Bing (1892–1964) had been employed at the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek (Library for Cultural Studies) run by art historian Aby Moritz Warburg for about a year when she wrote to him on January 29, 1923, telling him about a lecture by the philosopher Ernst Cassirer. In 1921, she had received her doctorate under Cassirer – it was he who found her a position at Warburg’s institution shortly after.

Initially, Bing worked as a librarian under art historian Fritz Saxl, the institute’s deputy director. In 1924 she became Warburg’s personal secretary and assistant and accompanied him on research trips to Italy. Her growing importance for the Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek is evidenced by the institutional diary kept from August 1926 to October 1929, in which Warburg expresses his appreciation of Bing with ironic epithets, such as “Herr Bingius” or “Bingiothek.”

As deputy director, Bing was involved from 1933 in saving the library’s approximately 60,000 volumes from the Nazis and shipping them to London. There, together with Saxl, she rebuilt the Warburg Institute. In the following years, the institution became an important contact point for scholars expelled by the National Socialists. Bing and Saxl worked to arrange new positions as well as to raise funds for the so-called Displaced German Scholars. In 1955, Bing became director of the institute and received an associated professorship at the University of London.

“I would like to participate […] in a systematic review and study of the rich source material available in the Turkish libraries.”

On November 2, 1941, the Hamburg Arabist Hedwig Klein sent a handwritten, two-page letter to Hamburg banker Dr. Rudolf Brinckmann (1889–1974). In it, she expressed her hope of being able to emigrate to Turkey in order to settle there as a trained Orientalist.

Hedwig Klein was 30 years old at the time. The daughter of a merchant from Antwerp, she had studied Islamic Studies, Semitic Studies and English Philology at Hamburg University. She completed her studies in 1937 with a doctoral thesis on a “text-critical partial edition of an Arabic manuscript on the history of Oman,” as she informs the letter’s recipient. Despite an equally successful oral examination in 1938, however, she was denied the doctorate due to the “tightened measures” against the Jewish population.

Since August 1941, Hedwig Klein, through the mediation of her doctoral advisor, Prof. Arthur Schaade (1883–1952), contributed to the editing of the Arabic Dictionary for the Written Language of the Present, evaluating contemporary Arabic literature and thus securing her livelihood.

Her emigration from Germany failed, and on July 11, 1942 Hedwig Klein was deported from Hamburg directly to the extermination camp Auschwitz-Birkenau and murdered shortly afterwards.

“At the seminar for German philology I am responsible for the coordination of the preparatory works for the dictionary of Hamburg dialect.”

With a bold, determined handwriting and a self-confident tone, Agathe Lasch (1879–1942) wrote her curriculum vitae, which she attached to her application for habilitation at the University of Hamburg in 1919. This curriculum vitae is an unusual document for a time when women had only recently been admitted to universities in Germany. The educational path of the then forty-year-old, who had fought her way through a series of detours to obtain her school-leaving examination, her university degree, the state examination and a doctorate, was therefore correspondingly arduous. From 1910 to 1916, she taught at the renowned Bryn Mawr College in the USA and unflinchingly pursued her research and publications on the development of Germanic languages. In 1926, when she was appointed to the Chair of Low German Philology at Hamburg University created especially for her, she was the first female professor in German studies nationwide. It is difficult to think of Agathe Lasch’s end without sadness and a sense of shame – her dismissal and loss of her professorship in 1935, followed by a publishing ban, the confiscation and destruction of her extensive private library, and finally her deportation to Riga, where she was murdered together with her two sisters in 1942. Read on >

Throughout her tenure as principal of the Israelite Girls’ School at Carolinenstrasse 35, which was originally founded as a school for the poor, Mary Marcus (1844–1930), also known as Mirjam or Marianne Marcus, strove to counteract the financial disadvantage of girls with the help of a careful upbringing and comprehensive education. In this way, she wanted to overcome the differences in status between “elementary school girls” and “girls of higher education.” Marcus was able to achieve her educational goals, sometimes in the face of resistance from the congregation’s executive board, which had long neglected girls’ education. Oriented on the curriculum of the Hamburg elementary school, a special focus was placed on the subjects of German, literature and foreign languages, which was intended to contribute to the social recognition of girls.

Sources attest to a strict but caring personality who was highly regarded by both her students and colleagues. Marcus made her commitment to girls’ education her life’s work. While in her day the so-called “teacher celibacy” still applied, which stipulated the dismissal of a female teacher in the event of marriage, Marcus remained unmarried throughout her life and did not start a family. By the standards of the time, her professional career was by no means ordinary. While women could become principals at smaller private schools, the management of state institutions was usually entrusted only to men.

“This is what we want to play for our girlfriends.”

Written in 1930 by teacher Lilli Popper, née Traumann (1903–1990), this account vividly depicts a female educator’s career at the beginning of the 20th century.

As a young girl, Popper attended the Jewish-liberal Loewenberg School in Hamburg-Rotherbaum, which followed the ideas of the art education movement. After graduating from the Helene-Lange-Oberrealschule in 1923 and training as a teacher two years later, she took a position at the Israelite Girls’ School [Israelitische Töchterschule] at Carolinenstrasse 35 in 1926. She taught primarily elementary school-level classes.

Striving to implement the reform pedagogical approaches of the time, she shaped her educational work in innovative and creative ways. For example, her second-year class maintained a class partnership with the third-year students of teacher Edith Behrend at the non-Jewish school Alsenstraße in Hamburg-Hoheluft. Joint excursions, performances and festivals, as well as pen-pal friendships, were intended to strengthen Jewish-Christian dialogue.

At the end of 1933, Popper, a convinced Zionist, decided to emigrate to Palestine. Her younger sister Susi, who had just finished her studies in education at the University of Hamburg and had now also taken up a job as a teacher at the Israelite Girls’ School, took over the children of the third school year.

In Tel Aviv, Lilli Popper worked at a school founded in 1934 for children of German immigrants and published Hebrew teaching materials.

Rosa Schapire’s (1874–1954) untiring commitment to the art of German Expressionism, which at the time was an avant-garde movement that set innovative impulses in the art scene, is evidenced by her letter of November 21, 1929 to the director of the Hamburg Museum for Arts and Crafts, Max Sauerlandt.

Schapire, who was one of the first women in Germany to receive a doctorate in art history and worked as a freelancer throughout her life, joined the Expressionist artists’ association Die Brücke in 1907 as a passive member and organized exhibitions for its artists, negotiated sales to private individuals and museums, gave lectures, and wrote reviews.

Along with art patrons Ida Dehmel, Martha Rauert and Selma von der Heydt, Schapire founded the Women’s Association for the Promotion of German Contemporary Visual Arts [Frauenbund zur Förderung deutscher bildender Kunst der Gegenwart] in 1916. The association, around which other local groups established themselves throughout Germany in the following years, initiated exhibitions and donations, including one to the Hamburg Kunsthalle. These women thus reformed the art institutions, whose museum directors were for the most part hostile to contemporary Expressionist art.

After the National Socialists came to power, Schapire published only under a pseudonym until 1937 and continued her lecturing activities in private circles. In August 1939, she managed to escape to England with a few postcards, watercolors, and prints by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and Emil Nolde, among others. Her other art possessions, including works by Max Pechstein, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Erich Heckel, as well as her private library were confiscated by the National Socialists and auctioned off.

“My conviction, my aspiration was for a system in which the differences between Jews and Christians, Englishmen and Germans, would become less and less important.”

Ingrid Warburg-Spinelli (1910–2000) published her autobiography, from which this passage is taken, in 1990. Her memoirs represent the testimony of a woman who pursued her unusual path as if it were a matter of course. Her actions were characterized by an ethical and political sense of responsibility, which also made it necessary to defy family conventions and gender-specific role expectations.

Ingrid Warburg-Spinelli grew up as the first child of Fritz and Anna Warburg in an upper-class Jewish family in Hamburg. After her school years in Hamburg, Stockholm and at the boarding school Schloss Salem, she studied German, English and philosophy in Heidelberg, Hamburg and Oxford from 1931. Her friendship with Adam von Trott zu Solz, whom she had met at Oxford, brought her into contact with circles of resistance to National Socialism at an early age. In Hamburg, Ingrid Warburg-Spinelli, who was interested in the idea of kibbutzim, was active for the Zionist organization Hechaluz. In 1935, she received her doctorate from the University of Hamburg under Emil Wolff. In 1936 she visited her uncle Felix Warburg in New York and did not return permanently to National Socialist Germany. In the following years, she became involved in Jewish aid organizations in the United States. In 1940, she was one of the founders of the Emergency Rescue Committee, which rescued more than 2,000 victims of Nazi persecution, including Franz Werfel, Marc Chagall and Walter Mehring, from occupied France. After the Second World War, she lived in Rome with her husband Veniero Spinelli, whom she had married in 1941 and with whom she shared a political commitment to a humane socialist society. (Text: Dirk Brietzke)

“Feminism comes naturally to me, and that’s how I act in everything I do, whether it’s professional or volunteer work.”

Deepening knowledge about Judaism in general and Reform Judaism in particular in liberal Jewish communities is Deborah Tal-Rüttgers’ central concern. She was born in Israel in 1950 and moved to Germany with her son in 1975, where her parents had returned two years earlier. After completing a German course, she obtained her Abitur (high school diploma) through night school and studied music and English in Kassel to become a teacher. In addition to her teaching activities, Deborah Tal-Rüttger and others founded the liberal Jewish congregation Emet weSchalom in 1995, of which she was the first chairperson for a long time. She led services, promoted Jewish learning, and edited the community newsletter ALON. From the founding of the Union of Progressive Jews in Germany in June 1997 until the summer of 2020, Deborah Tal-Rüttger served on its board and, as vice chair, was almost continuously responsible for liturgy and education. Together with Rabbi Dr. Gábor Lengyel and Cantor Yuval Adam, she has led services at the Reform synagogue for Hamburg’s Unity congregation since 2018 and offers learning sessions on Jewish religion, tradition and culture. Her work also includes teaching girls and boys who are becoming Bat and Bar Mitzvah, respectively. In this short video clip, DeborahTal-Rüttger talks about the various aspects of her educational work.

Women had limited opportunities to participate in public political life until the modern era. Jewish women were doubly excluded: because of their gender and as Jews. Until the Vormärz, the majority of Jewish women and Jews were Orthodox conservatives and did not hold a pronounced political interest.

The field of care (Tzedakah) traditionally represented an activity “both religiously legitimized and compatible with contemporary gender roles” in which women could exert influence and hold positions that were otherwise denied to them.

During the Empire and the Weimar Republic, the majority of Jews were active in liberal and Social Democratic circles. Women increasingly appeared as political actors, participated in social debates, and championed various causes. In the Weimar Republic, women gained the right to vote and to stand for election for the first time. In Hamburg’s Jewish congregation these developments resulted in a gradual adjustment in 1919 and 1930.

During National Socialism, participation in public political life became impossible due to the policy of repression and persecution. In the postwar decades and up to the present day, surviving, returning and immigrating Jews were active in various sections of the political spectrum, both within the Jewish congregation and for general political issues.

The anti-fascist commitment of the well-known contemporary witness Ester Bejarano to the commemoration of National Socialist crimes is just as much an example of this as the educational work against antisemitism of Mascha Schmerling or the committee work of the first female congregation board member Gabriela Fenyes. Käthe Starke-Goldschmidt rescued numerous documents and drawings from Theresienstadt, which, together with her memoirs, represent an important legacy for posterity. Sidonie Werner, Helene Bonfort, Julie Eichholz, and Fanny David are four examples of representatives of the women’s movement.

“The association aims, by uniting Jewish women and by the respective activities of its branches, to foster the highest and most ideal interests of humanity and to elevate the moral and intellectual character of Jewry and to develop it.”

Since its inception, the association focused in particular on expanding education for women and girls and promoting employment opportunities for women, thus joining the middle-class women’s movement in Imperial Germany in its demands for women’s access to higher education, professional training and qualified employment opportunities. The goal was to make women economically independent and offer them the possibility of a self-determined life as an alternative to the existing middle-class ideal of women as wives, housewives, and mothers. In addition, social work to help the needy is clearly emphasized in §2 as well. During Sidonie Werner’s tenure as chairperson, the association established numerous new social projects. In 1909, an employment agency for women was set up in order to reduce poverty among women. A project for women run by women, it proved very successful. Since the middle-class women’s movement had established its own employment agencies, it is safe to assume that only Jewish women were placed through this agency. The Israelite Boarding House for Girls opened in Hamburg the same year. Its independent association had strong ties to the Israelite-Humanitarian Women’s Association Israelitisch-humanitärer Frauenverein due to Sidonie Werner’s involvement along with that of several other board members. Read on >

“Hopefully, I will at some point have the opportunity to do you a favor, however small.”

In her letter of November 6, 1912 to an unnamed “Herrn Syndikus” [a company lawyer], the women’s rights activist Julie Eichholz, née Levi (1852–1918), thanked him for his support of her charitable Julie Eichholz Foundation. She had established the foundation in 1912 upon her resignation as chairwoman of the Federation of North German Women’s Associations, which she had founded in 1902. Without the “help so graciously given” by the lawyer, Eichholz notes, she “certainly would not have reached her goal.” According to its statutes, the foundation’s goal was to use the interest earned on its capital “in the spirit of the women’s movement” for contributions to scholarships, aid to education, or the “commercial professional life” of women. Julie Eichholz together with Helene Bonfort belonged to the “moderate” wing of the bourgeois women’s movement, which in the years before the foundation was established had led to disagreements with “more radical” bourgeois women’s rights activists within the Allgemeiner Deutscher Frauenverein (ADF), as for example with Lida Gustava Heymann. Julie Eichholz had been active in Hamburg since 1896, where she and other women founded the Hamburg chapter of the ADF, which she chaired from 1900 to 1904. She was succeeded by Helene Bonfort. At the same time, Eichholz was active regionally and nationally, particularly in the area of legal protection for women, and in 1911 she founded the Legal Protection Association for Women [Rechtsschutzverein für Frauen]. Furthermore, she campaigned for the abolition of §218 and for a better legal position of female service personnel.

In keeping with the spirit of its namesake, the Helene Bonfort Foundation was intended to award scholarships to girls from poor families, thus enabling them to pay their school fees for an education in the social work sector. The foundation, which was established in 1916 with the capital of friends, thus served to continue the socio-political commitment of Helene Bonfort (1854–1940) beyond her death.

Born in Hamburg, she attended a secondary school for girls and subsequently trained as a teacher. She took up her first post in 1872 at the Paulsenstift school in Hamburg’s old town, whose director at the time was the pedagogue Anna Wohlwill (1841–1919). While later working at a school in Düsseldorf, Bonfort met her future partner, the teacher Anna Meinertz (1840–1922), and both became involved in the women’s movement and welfare work in the following decades.

In 1896, for example, they initiated the Hamburg chapter of the Allgemeiner Deutscher Frauenverein (ADF), of which Bonfort was president for the first four years and from 1904 to 1916. The ADF belonged to the moderate wing of the bourgeois women’s movement in the German Reich. Its objective was a gradual improvement in women’s social participation and influence rather than a demand for immediate political equality.

Central to Bonfort’s commitment was the idea of extending the traditional caring role of mother to the whole of society – the concept of “spiritual motherliness” as “women’s cultural task.” Thus, the bourgeois women’s movement was instrumental in the development and establishment of social work as a profession. In line with this trend, Bonfort brought about the founding of the Social Women’s School, later the Social Pedagogical Institute, in 1917.

Fanny David wrote this letter to “Frau Doktor” on June 30, 1917, at the age of 24 in Hahnenklee in the Harz mountains, where she was spending a vacation prescribed by a doctor. The letter is part of the Richard and Ida Dehmel estate kept at the Hamburg State and University Library, which is why it can be assumed that Ida Dehmel, wife of Dr. Richard Dehmel, was the recipient. The letter’s formal address expresses respect and admiration. The following account of the dispute David had with her superior, Helene Bonfort, due to her taking a medical leave lets the author’s emotions boil up again, as the quotation shows. Bonfort had co-founded the Hamburg chapter of the women’s association ADF and, at the time the letter was written, chaired the women’s committee of the Hamburg war relief fund [Hamburger Kriegshilfe]. The letter illustrates the difficult relationship between the two women. At the same time, it provides insight into Fanny David’s early experiences in welfare work, which is identified as a female field of activity.

Fanny grew up in Altona as the eldest daughter of Max and Martha David and became involved in welfare work as soon as she left school. She quickly rose to the position of inspector in the newly created Welfare Office in 1921 and then took over the management of the Hamburg-Barmbek Welfare Office. In this position, she was part of the circle of advisors to the president of the Welfare Office. After her dismissal in 1933 due to Nazi legislation, Fanny David worked in the counseling center of the Jewish congregation, headed the economic aid office and was deputy of the welfare office. In Theresienstadt, where she was deported on June 23, 1943 together with her mother and sister, she belonged to the camp self-administration. On October 28, 1944, she was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where she was presumably murdered shortly after her arrival.

“This cannot end well.”

In 1975, Käthe Starke-Goldschmidt published her memoirs of her time in the Theresienstadt [Terezín] ghetto and transit camp under the title “Der Führer schenkt den Juden eine Stadt” [The Führer Gives the Jews a City]. […] Particularly stirring is the description of her deportation, which, despite its sober far-sightedness, is highly emotionally charged.

Käthe Starke-Goldschmidt was born on September 27, 1905 and grew up with her older sister Erna in Altona. Her father, banker Iska Goldschmidt, died in 1938, her mother Hulda Goldschmidt in 1941. Käthe Starke-Goldschmidt began studying German, philosophy and art history in 1927. She first studied theater and literature in Heidelberg, and later in Munich. There she was active as an actress and director. In 1935 she had a son with Martin Starke, a Jew and political opponent of National Socialism, her son survived the National Socialist era disguised as a non-Jewish child. In 1937 she returned to Hamburg and was initially employed as a dramaturge in the Jewish Cultural Association. After it was banned, she worked in the Jewish congregation. Käthe and Erna Goldschmidt were forced to move into a “Judenhaus” at Beneckestraße 2 in September 1942. There was an office of the Secret State Police (Gestapo) in the same building. On June 23, 1943, “in the bright light of a cheerful summer day,” as she writes in her memoirs, both were deported to Theresienstadt with 106 other women and men, including many employees of the Jewish congregation. In the summer of 1943, Käthe Starke-Goldschmidt certainly knew through her work in the congregation, which was administratively involved in the deportations, what lay ahead of her. Read on >

“I declare that I accept my election as a member of the Board of Directors of the Jewish Congregation of Hamburg.”

Gabriela Fenyes was elected to the Executive Board of the Jewish Congregation in Hamburg on March 13, 1991. The certificate and declaration testify to this election process and the acceptance of the election. The election had become necessary when, after the electoral victory of the Kadima group in the advisory board elections at the end of 1989, to which Fenyes belonged, the previous members of the board had resigned due to political differences within the congregation. In addition to Gabriela Fenyes herself, the newly elected board included Dr. Mauricio Dessauer, Michael Heimann, Albert Nassimi, and Michael Warman. Fenyes was responsible for public relations and social affairs / integration. The first term was marked by the conflict over the area of the Jewish cemetery in Ottensen and the immigration of Jews from the former CIS states. In November 1991, Fenyes was one of the speakers at the opening of the exhibition “400 Years of Jews in Hamburg” at Hamburg’s History Museum, which helped to raise public awareness of Jewish life in the city. The second term after Fenyes’ re-election was overshadowed by antisemitic and xenophobic attacks on the synagogue in Lübeck, which revealed a radicalization of right-wing violence. The Hamburg congregation was also responsible for Jewish affairs in Schleswig-Holstein. Fenyes served as a member of the congregation board for a third time during a short period in 2007/2008. In addition to her board activities, she was delegated to the NDR Broadcasting Council on behalf of the Jewish congregation and was a member of the board of the Hamburg group of the Women’s International Zionist Organization (WIZO) from 1980 to 1994.

“No one is just Jewish, there are many, many aspects to an identity, such as being a woman or being a mother or being German.”

Mascha Schmerling, born in 1980 and a member of the Jewish congregation in Hamburg, has been actively involved in work to prevent the spread of antisemitism since 2014. In this short video excerpt, she reflects on the question whether being a woman plays a role in her work. Currently, Mascha Schmerling is one of the project coordinators of "Meet a Jew," a project run by the Central Council of Jews (www.meetajew.de) that aims to provide first-hand information about current Jewish life in Germany. By having Jewish youths and adults volunteer to visit schools, universities, sports clubs and other institutions and report on their individual everyday lives as Jews, the project aims to facilitate encounters that open up space for conversation and thus help to break down prejudices. In a longer video version, Mascha Schmerling pleads for a differentiated portrayal of Jewish people in the media and school textbooks and for giving the word “Jew” an individual face beyond the popular symbolic images. This also includes letting people have their say who understand their Jewishness as one, but not the only facet of their individual identity(ies). According to Schmerling, her work is also about communicating Judaism beyond religion as a living tradition and diverse culture.

Esther Bejarano, who was born Esther Loewy in Saarlouis on December 15, 1924, came to Hamburg with her family in June 1960, where she built up a new existence by running a small boutique, among other things.

After her liberation by U.S. and Soviet soldiers in Lübz, Esther Bejarano emigrated via the so-called Buchenwald kibbutz, the collection point for emigration to Palestine. In Palestine she met her future husband and together they started a family. Esther’s poor health – doctors advised her to return to Europe due to the Israeli climate – and the fact that there was no possibility of legal conscientious objection for her husband in Israel, eventually prompted their decision to emigrate. Germany was the obvious choice because of their existing language skills. Thus, after 15 years in Israel, the family moved to Hamburg in June 1960, where Israeli friends who had recommended the city were already living. The city held no memories of her parents for Esther – her basic condition for the venture of a new beginning. Nevertheless, the early years were difficult: the housing shortage of the postwar period, a difficult start in school for the children due to discriminatory regulations, and the distrust towards non-Jewish Germans all represented challenges for the family. During this first period, the Jewish congregation was an important point of contact; it supported the family, for example, in finding housing. Most of their friends were also Jewish at the beginning. The school situation was resolved through Esther Bejarano’s courageous intervention. Her husband Nissim was able to find work quickly, and so nine years after her arrival in Hamburg, Esther ventured to open her own store.

“All the anti-fascists came and we talked,” recalls Esther Bejarano of the time when she ran her boutique Sheherazade at Hellkamp 14 in Eimsbüttel, where she sold jewelry from Israel and around the world.

As early as the 19th century, middle-class Jewish women were active as salonières in the cultural sphere.

“From the beginning of the 20th century, Jewish artists played a significant role in the awakening movements of arts and culture. In the liberal-pluralist cultural scene of the Weimar Republic, they were represented in all artistic fields and styles.”

Women were no longer mere muses, but were perceived as artists themselves. They organized themselves, for example, in the Women’s Association for the Promotion of German Visual Art [Frauenbund zur Förderung deutscher bildender Kunst] founded by Ida Dehmel and Rosa Schapire in 1916 or the Association of Women Artists and Art Patrons [GEDOK - Gemeinschaft der Künstlerinnen und Kunstfördernden e. V.] founded by Ida Dehmel in 1926. Women also played a role as patrons (Emma Budge or Ida Dehmel), were members of the Hamburg Secession (Anita Rée, Gretchen Wohlwill), were involved in theater (Ida Ehre), ran art schools for women, appeared on the radio, and promoted avant-garde art. Nevertheless, they represented a minority.

After the National Socialists banned Jews from all professions, only the Jewish Cultural Association offered an opportunity to work. Numerous women artists fled into exile or were murdered by the Nazis. Many of the women artists fell into oblivion. Women like Ida Ehre, who took over the directorship of the Hamburg Kammerspiele as early as 1945, helped to rebuild the cultural scene after the war. Since 2008, the Jüdischer Salon am Grindel e.V. has offered a platform for Jewish culture.

This chapter highlights examples of the work of Jewish women artists in dance (Erika Milee), the visual arts (Gretchen Wohlwill, Anita Rée), literature (Grete Berges), acting and theater management (Ida Ehre), and it also discusses female patrons (Emma Budge, Ida Dehmel) and an illusionist (Rosa Bartl).

„Milee School Hamburg.“

Erika Milee (1907–1996, originally Erika Michelsohn) trained as a dancer from 1926 with Rudolf von Laban and Albrecht Knust and opened her own dance school at Rothenbaumchaussee 99 in 1928 at the age of 21. Newspaper advertisements from the 1930s, published in Monatsblätter des Jüdischen Kulturbundes Hamburg, promote the versatile range of courses offered by the Milee School at Rothenbaum. The school’s logo and Erika Milee’s portrait photo defined the school’s brand and suggest that its director had a specific advertising strategy. In addition to her management of the school, Erika Milee trained at the Folkwangschule in 1930 and at the municipal theaters in Essen, where she participated in productions by Kurt Jooss. Back in Hamburg, Erika Milee became involved in the Jewish Cultural Association, for whose dance section she was mainly responsible, and performed successful dance evenings with her students. She was also concerned with improving the dance education of her students, who were exclusively Jewish since 1935. In 1939, Erika Milee fled Nazi Germany and arrived in Paraguay via Italy and Portugal, where she headed the dance department of the Academy for Theater, Music and Painting in Ascunción. In exile she taught and choreographed; alone and with her dance group she performed in various South American countries and opened a dance school in Brazil in 1953. Erika Milee returned to her hometown in 1959, where she again directed a dance studio and held teaching positions.

Gretchen Wohlwill was a Hamburg-born painter who, as a student of the Académie Matisse in Paris, developed a painting style influenced by French avantgarde art. She was a member of the Hamburg Secession, an artists’ group founded in 1919, which dissolved on May 16, 1933, after the Nazi regime had called for the exclusion of its Jewish members. It was probably no coincidence that she painted Fraenkel’s posthumous portrait since there was a personal connection between the artist and the portrayed person: Her brother Friedrich Wohlwill, also a physician, had worked for Eugen Fraenkel at the pathological institute and had been his deputy for several years.

Because of their Jewish origin, the Wohlwill siblings were persecuted by the National Socialists. Gretchen emigrated to Portugal in 1940 and only returned to Hamburg in 1952, where she died on May 17, 1962 at the age of 84. Read on >

Anita Rée’s 1925 painting “White Trees in Positano” can be considered the most important work from her years in Italy. […] Fascinated by quattrocento painting and especially Piero della Francesca’s frescoes in Arezzo, she eventually developed a style that was very much in the vein of New Objectivity. […] While this work is considered a highlight among Rées Positano vistas today, it was controversial at the time. The history of this painting, which was long considered lost, hints at Anita Rée’s own fate. Although she never identified as Jewish, she fell victim to National Socialist persecution. […]

After the first World War, a Secession group formed in Hamburg in 1919, and Rée was among its founding members. The Hamburg Secession developed into an elitist artist group which presented its most recent works in annual exhibitions. After having spent a year painting in the Austrian town of Grins in Tirol in 1921, she moved to Positano in Italy, where she stayed and worked on her own until 1925. The charming and secluded fishing village on the Gulf of Salerno had been a well-kept secret among writers and painters. As her works from this period show, she also visited various artistic and cultural sites in Italy, including Rome, Ravenna, Southern Italy and Sicily, sometimes in the company of other artists or friends. Read on >

Upon Henry Budge’s death a testation jointly made with his wife came into effect according to which their collection of decorative arts acquired in Germany was to be donated to the MKG after their deaths. In 1930 Emma Budge expanded the intended donation by willing that the villa was to be given to the city of Hamburg for charitable use. The Budge Palais was to become an outpost of the museum showcasing upper-class bourgeois life in Hamburg and the work of the city’s art collectors and patrons, with the Budges and their art collection as an example. A few months after the National Socialists came to power, Emma Budge changed her will and appointed her Jewish relatives as heirs instead. She also named four Jewish executors who were charged with administering her estate according to her wishes and for the benefit of her heirs. At the same time she did demand an appropriate "realization" according to the best business strategy. She expressly excluded the city of Hamburg from benefitting in any way. Read on >

“The Women’s Association for the Promotion of German Visual Art was founded in the desire to build bridges between creators, enjoyers and museums.”

Helping modern art to gain attention, recognition and a breakthrough was an important concern for Ida Dehmel (1870–1942). As a salonière, art promoter and poet’s muse, she knew that in order to tear down the bulwarks of a conservative understanding of art, she and like-minded people would have to achieve a leverage effect that had to start where the art canon is determined – in the museums. Hamburg-based Rosa Schapire (1874–1954), Germany’s first female art historian with a doctorate, was a profound connoisseur and champion of Expressionism. Her understanding of art, coupled with Ida Dehmel’s organizational talent, was the recipe for success for the Women’s Association for the Promotion of German Visual Art [Frauenbund zur Förderung deutscher bildender Kunst], which was founded in Hamburg in 1916. Led by Ida Dehmel and Rosa Schapire, the Women’s Association [Frauenbund] was intended to bring together artists, private art collectors, and public collections and to be beneficial to all parties involved. Shows such as the 1918 graphics exhibition in Hamburg were an important instrument for generating income and promoting new art forms.

In addition to Dehmel as executive chairwoman and Dr. Schapire as secretary, the main board included art collectors such as Martha Rauert, Lotte von Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Selma von der Heydt. Branches were set up in numerous German cities, and sales exhibitions were organized. Within two years, the initiative had 600 members. In the shadow of great, not always progressive museum directors of the era, the Women’s Association [Frauenbund] pursued its goal. It circumvented acquisition policies with gifts and placed paintings by Expressionists such as Karl Schmidt-Rottluff in leading museums for the first time.

Ida Ehre (1900–1989) is one of the most famous cultural figures in Hamburg’s history. In 1985, she became the first woman to become an honorary citizen of the city, and schools and squares are named after her today. The Hamburger Kammerspiele theater at Hartungstraße 9-11 in the Grindelviertel is also inextricably linked with her name. Ida Ehre was the artistic director of the theater from 1945 until her death in 1989. Shortly after the end of the war, on June 28, 1945, Ida Heyde, née Ehre, wrote a letter to the British military government requesting “the granting of a license for the operation of a theater.” According to the legislation of the time, her husband Bernhard Heyde had to give his consent as a co-signatory. Ida Ehre’s professional ban, failed emigration and concentration camp imprisonment in Fuhlsbüttel resonate in the letter as “the frightening experience of past years.” The focus, however, is on her plans for a theater to be founded in the former rooms of the Jewish community center in the proven Kammerspiel tradition, which at the same time sought to contribute “to the development of new thoughts” by having authors of all nations name the “human problems and problems of the world, of which we were not allowed to know anything for 12 years.” Here Ida Ehre also refers indirectly to the democratization and denazification efforts of the British military government. The letter concludes, among other things, with information about Ida Ehre’s career and the naming of references. Read on >

“I returned to the city of my origin […] my childhood, youth, and years of womanhood, back to a world that I had considered lost forever and that had become unreal to me.”

In an article titled “Wiedersehen mit Hamburg” [Return to Hamburg], writer, translator and literary agent Grete Berges, who exiled from Germany in 1936, describes her return to the city from which she was expelled by the National Socialists. Seventeen years have passed between her escape and her return visit. In 1953 she accompanied the Swedish writer Per Olof Ekström, whose agent she was, on a business trip to Hamburg. On the occasion of this return, her short article “Wiedersehen mit Hamburg” [Return to Hamburg] was published in the Hamburger Abendblatt on July 22, 1953. […] With the help of the Swedish writer and Nobel Prize winner Selma Lagerlöf, Berges finally received a residence permit for Sweden in 1937. In Stockholm, where she lived until her death, she set up a literary agency – a job she herself called an “emigration profession.” She tried to promote other exiled writers, such as Hildegard Johanna Kaesar, Pipaluk Freuchen and Gertrud Isolani. She also worked as a translator of Swedish authors for the Swiss and German book market. Read on >

“Zauber-Bartl” was the name of a specialty store for magicians that had several locations in downtown Hamburg from 1910 until the 1960s. The owner of the well-known shop that belonged to the Leichtmann magic empire (Berlin, Cologne, Munich, Hamburg) was Janós Bartl. His wife Rosa acted as a saleswoman with a lot of practical expertise since she was considered a magic icon by experts. The magic props were advertised in catalogs. Here you can see the magic cigarette case “Etuiso” patented by Rosa Bartl.

After difficult years during the First World War, the magic business experienced a great upswing at the beginning of the 1930s. When the National Socialists came to power, the members of the Leichtmann family were targeted by National Socialist persecution measures. Her “privileged mixed marriage” with the non-Jewish Janós offered Rosa and their children Hans and Elly some protection and ensured their survival. In 1950, Rosa Bartl was able to join the company as an equal partner. Four years after Janós’ death, Rosa Bartl had to give up her business premises in the city center in 1962 and moved the magic shop to her private villa at Warburgstraße 47. Rosa Bartl passed away on September 23, 1968.

“Since the early modern period the economic activities of Jews in Germany […] in general differed in some ways from those of the general population: due to legal and political limitations Jews were more likely to work in trade and finance than in the crafts or farming. [...] In the 19th century Jews advanced socially through the process of becoming assimilated into the bourgeoisie [Verbürgerlichung]. As this process increasingly resulted in higher education levels and more academic qualifications, their occupational patterns changed.“

Proportionally, Jews were more likely to belong to the middle class, which probably also explains why Jewish women were less likely to be employed than non-Jewish women until well into the 20th century.

After being systematically pushed out of the economy and all professional areas during National Socialism, the occupational profile of the Jewish community in the first decades after the Second World War shows a noticeable concentration in real estate and the textile industry. Despite the legal equality of men and women codified in the Basic Law of 1949, a woman’s professional activity was dependent on compatibility with her marriage and family and the husband’s consent until the 1970s.

The women presented in this chapter, among them two physicians (Anita de Lemos and Rahel Liebschütz-Plaut) and a lawyer (Käthe Manasse), show that the so-called liberal professions offered women opportunities. At the same time, Manasse stands as an example for a larger group of female and male lawyers who re-migrated after 1945. Sonia Simmenauer, a concert agent and founder of Café Leonar, exemplifies a multifaceted professional biography in which modern salonière and entrepreneur merge.

In addition, it becomes clear that the (unofficial) forms of gainful employment sometimes undermined legal barriers (thus the examples of Glikl of Hameln and Lucy Borchardt). To this day, female career paths are often less straightforward, a disproportionate number of women work part-time, women are less likely to be represented in leadership positions and are paid less than men on average.

“But after all her suffering and pain she bore nothing but the voice of the wind. So, my God and great King, it happened to us too.”

Glikl, daughter of Judah Leib, was born in Hamburg in 1646 and died in Lunéville in Lorraine 1724. A daughter of a trader and businesswoman, she was married at the age of 14 to a businessman named Haim of Hameln, with whom she operated a firm that traded in precious metals and stones. Glikl bore 14 children, of whom 12 survived past infancy.

Glikl’s text was not written as a diary that chronicled events immediately as they transpired. Instead, Glikl produced her memoir as a reckoning with the past, prompted by family hardship. Glikl appears to have worked on the text in two distinct stages. She tells her children, for whom the memoir was written, that she was first motivated to stave off her melancholia after the death of her husband Haim (1690). But a significant portion of her remembrances are dedicated to a retrospective self-fashioning after the bankruptcy and death of her second husband, Cerf Levi of Metz (1712). Whereas the first union was characterized by affection, partnership, and prosperity, the second was marred by financial ruin, poverty, and hardship. Her recollections of the Sabbatean movement Jewish messianic movement of the followers of Schabbtai Zvi in Hamburg are therefore also part of a backward glance through history, colored by the changing fortunes of her family. Read on >

Born in 1877, Borchardt first became involved in the shipping company in 1915, when she had to fill in as general manager for her husband Richard Borchardt, who had gone to war. He had taken over the company from its founder, Carl Tiedemann, in 1905. “Fairplay” had been the name of the first tugboat Tiedemann had bought for his fledgling company in 1895, and he decided to choose it for his company. It was supposed to create trust, thereby giving the shipping company an advantage on the international market. When her husband died in 1930, Lucy Borchardt became sole director of the well-respected company. […] Lucy Borchardt was not only a well-respected Hamburg citizen, she also actively supported Hamburg’s Jews. She joined forces with Naftali Unger from Palestine, who had spent some time in Hamburg, and in 1935 organized the Zionist seafaring hakhsharah. The hakhsharah was a preparatory program that enabled young German Jews to learn a trade and thus qualify for emigration to Palestine. Due to Borchardt’s involvement, her shipping company became the location where professional retraining was held. Program graduates received certificates by the Palestine Office for immigration that allowed them to leave Germany. At the same time, two kibbutzim were founded in Palestine that established shipping as an industry in there and were thus able to employ the new immigrants. Read on >

“… for while sick women are being treated, the sick men would just continue to infect healthy women.”

In the early summer of 1921, Hamburg’s city assembly decided to abolish brothels since they were considered a haven for disease and alcoholism and because of the exploitative conditions under which brothel keepers and pimps operated. This decision resulted in the “Hamburg brothel controversy,” passionately fought by representatives from the public health and political sectors, which essentially revolved around the city’s regulation of prostitution. In a 1926 essay, the physician Anita de Lemos argues that the housing of prostitutes in supervised houses, as demanded by the bourgeoisie, was unsuitable for combating the rampant problems (a rapidly increasing number of prostitutes, sexually transmitted diseases).

Anita de Lemos made the medical care for women suffering from venereal disease her special concern and thus became one of the most influential female physicians in Hamburg during the Weimar period. Born in Hamburg in 1888, she came from a traditional Sephardic family and had trained as a physician for skin and venereal diseases. Anita de Lemos and other experts called for better health care and suggested to include the men visiting prostitutes in regulatory measures. Her arguments prevailed in the “Reich Law to Combat Venereal Diseases,” passed a year later, which mandated the consistent monitoring and treatment of venereal disease patients, but prohibited the quartering of prostitutes in special buildings and streets.

Due to antisemitic legislation, she lost all her positions in 1933 and subsequently emigrated to the USA in 1938, where she worked first as a nurse, later as a forensic expert and finally in her own practice. She died in New York in 1976.

“I hereby request my appointment to the judicial service as a district court judge.”

Käthe Manasse (1905–1994), née Loewy, was born into a merchant family and grew up in Berlin in a middle-class Jewish milieu. After a modern school education, she first began studying national economics, but quickly switched to law. She earned her doctorate with a brilliant dissertation, passed the assessor’s examination in 1932, and became a judge. After she was forced to resign from office the following year due to National Socialist legislation and was disbarred a short time later, she emigrated to Haifa with her husband in 1938.

When the couple decided to return to Germany in 1949, Käthe Manasse began working in the Office for Reparations in Hamburg. At the same time, as can be seen from this letter of November 22, 1950 to Mr. xxx of the Hanseatic Higher Regional Court, she undertook efforts to be reinstated as a judge, and in 1952 she succeeded. She quickly made a career for herself and became district court director in 1962.

In addition, she was active in the Jewish congregation, was a member of its advisory board, and founded the group of elders. She also served as chairwoman of the women’s charity of the Magen David Adom (Red Star of David) in Hamburg and in various women’s professional legal organizations.

“My cause is making an impression on those involved.”

Rahel Plaut (1894–1993) was the first woman to habilitate at the Medical Faculty of Hamburg in 1923 and the third woman ever to do so in Germany, with a thesis on isometric contractions on skeletal muscle.

In this excerpt from her diary of 1922, she describes her visit to the 34th Congress of the German Society of Internal Medicine in Wiesbaden in April 1922. The congress of internists was one of the most important congresses of scientific exchange. In 1922, only one woman, the internist Klotilde Meier (1894–1954), gave a lecture. Thanks to Otto Kestners (ehem. Cohnheim) who ceded his time to contribute to the discussion to her, Plaut was able to present her research results, which earned her recognition from her colleagues.

The account is contained in diary no. 19 of a total of 73, which Rahel Liebeschütz-Plaut wrote from the age of eight to 98. […] Some volumes have large gaps of one to two months while others cover every single day. She rarely gives information about her feelings, and her opinions about other people sometimes turn out to be quite harsh. Her diaries are a treasure trove of lived history and provide insight into personal, professional and political matters as well as into the inner workings of institutions such as the Eppendorf Hospital. Read on >

Sonia Simmenauer was born in the USA and spent her childhood in Paris. After her studies, she started her own business as a concert agent, Impresariat Simmenauer, in 1989. In 2008 she founded Café Leonar and together with others the Jewish Salon at Grindel [Jüdischer Salon am Grindel e.V.] The following text was written by Sonia Simmenauer.

2007. An old, rather dilapidated house. A print shop in the middle of Grindelhof. A place that is somehow dreamlike, a little oasis. A space for history(s).

The printer – Wolfgang Fläschner – who was born in the neighborhood and has always dealt with the vacuum left by the war and the Shoa. My biography as a returnee, daughter of a Hamburg Jew who had to flee with his family in 1938. The time was ripe for an attempt to unite with and through culture, memory and tradition.

The birth of the salon was not the idea of a single person, but of a group of friends who wanted to occupy a space for discussing, questioning and seeking tolerance. I had the location, it made me a hostess and, in retrospect, a salonière. It is an honor for me to be part of a beautiful tradition along with wonderful women.

Are salons today held more by women or by men? I know of no empirical studies on this question. I think that the salon is a mirror of society and the division of tasks in it, and it is therefore a question of generations. Also, as it takes place at the boundary between the private and public space, each salon, as a place of exchange, beyond commercial and professional institution, will always have a unique personal profile.

In this exhibition, many important women were left out. We were not able to find suitable self-testimonies in every case. In addition, we wanted to show the diversity of life worlds and have therefore limited ourselves to exemplary and, in most cases, extraordinary female protagonists.

We would have liked to include many more women in the lineup. Therefore, we have compiled a small preview of how the exhibition might grow in the future. Of course, this list still does not claim to be complete. To be continued!

Concept: Sonja Dickow-Rotter, Anna Menny, Anna von Villiez. Texts: unless otherwise indicated: Sonja Dickow-Rotter, Anna Menny. Technical implementation: Daniel Burckhardt. Translation: Insa Kummer.

The chapter “Learning, Teaching and Research” was realized in cooperation with the Memorial and Educational Site Israelite Girls’ School, texts: Aline Philippen.

Funded by #2021JLID - Jüdisches Leben in Deutschland e.V. with funds from the German Federal Ministry of the Interior for Building and Housing.

As of: February 23, 2021.