Caring for the poor and weak within one’s community, both in material form and by individual acts, is a fundamental part of the religious tradition of Judaism. The term Tzedakah (justice) describes a comprehensive understanding of charity aimed at social equality. Charity as such is a central religious obligation (mitzvah) which applies to members of all social classes, including the poor, and to both sexes alike. In the centuries of diaspora, spent in a latently and sometimes openly hostile environment, a system of social welfare had developed within the Jewish communities which became active in cases of individual or collective need. It included various organizations and support funds taking care of a community’s poor or sick members, but also of strangers passing through the community. Initially all these efforts were organized and funded by the communities themselves. In the Early Modern Age, volunteer religious and charitable associations gradually took over. While the burial societies (chevra kadisha) existing in all major Ashkenazi communities in the 17th and 18th century were primarily tasked with caring for the sick and organizing funerals, they eventually became the core of further charitable work. Similar to guilds, the chevrot were exclusive associations of a community’s elite and as such played an important social role within the Jewish community. In the first half of the 19th century which saw the long process of the Jewish population’s transformation, meaning the improvement of their social position, their assimilation into the bourgeoisie, and their secularization, the system of charity changed, too: traditional societies were replaced by modern associations open to all members of the community and differing widely in terms of their structure and role. Due to their specific overlapping of both traditional and modern elements, Jewish associations and the charitable organizations in particular are considered the emblematic institutions of German Jewry. They represent an expression of the desire for both integration and individuality.

During the National Socialist regime and after 1945 Jewish charity initially focused again on practical support, primarily by providing material resources to cover everyday needs. By and by, topics such as education, youth work, and leisure activities were taken up again as well.

For the Early Modern period, the number of Jewish paupers can only be estimated. It is important to keep in mind that well into the 18th century, a large part of them were counted among the “itinerant paupers” who could not settle in any community while congregations had the right to decide on the admission of new members. This was also the case in Hamburg, where the Regulation on Jews Judenreglement of 1710 codified both the congregation’s rights (taxation, finances, and jurisdiction) and obligations (charity, religious matters, and schooling). Nevertheless, social data compiled based on the congregation’s tax lists show that at the beginning of the 19th century, at least two thirds of the congregation’s members were considered poor. While their share shrank steadily in the following decades, it was still 40 percent at mid-century and between 20 and 30 percent at the time of the founding of the Kaiserreich. Up until World War I, the number of those relying on charity had continued to decrease, but it rose again in the 1920s as a result of war and inflation before growing into a mass phenomenon during the era of National Socialism. After 1945, survivors lived in precarious circumstances, and joining the middle class was a slow process by no means all of them managed to accomplish. A similar situation was experienced by the families from countries of the former Soviet Union who have settled in Hamburg since the 1990s and for whom emigration almost invariably meant a lowering of their social status.

The municipal welfare system secularized by the founding of Hamburg’s General Institute for the Poor Allgemeine Armenanstalt in 1788 explicitly excluded Jews. Nevertheless, the Jewish community took the structure of municipal welfare as a model and, alongside the traditional associations, began to create a modern welfare system when it founded the Israelite Almshouse Israelitische Armenanstalt in 1817 / 18: volunteers looked after the needy in the newly zoned districts and collected their applications which were decided on after thorough review by a commission. At the same time, several institutions and associations devoted to specific problems were founded. They worked to stop begging in the streets, for example, or granted loans or distributed school clothing to poor children; they also founded a hospital, orphanages, nursing homes, and homeless shelters.

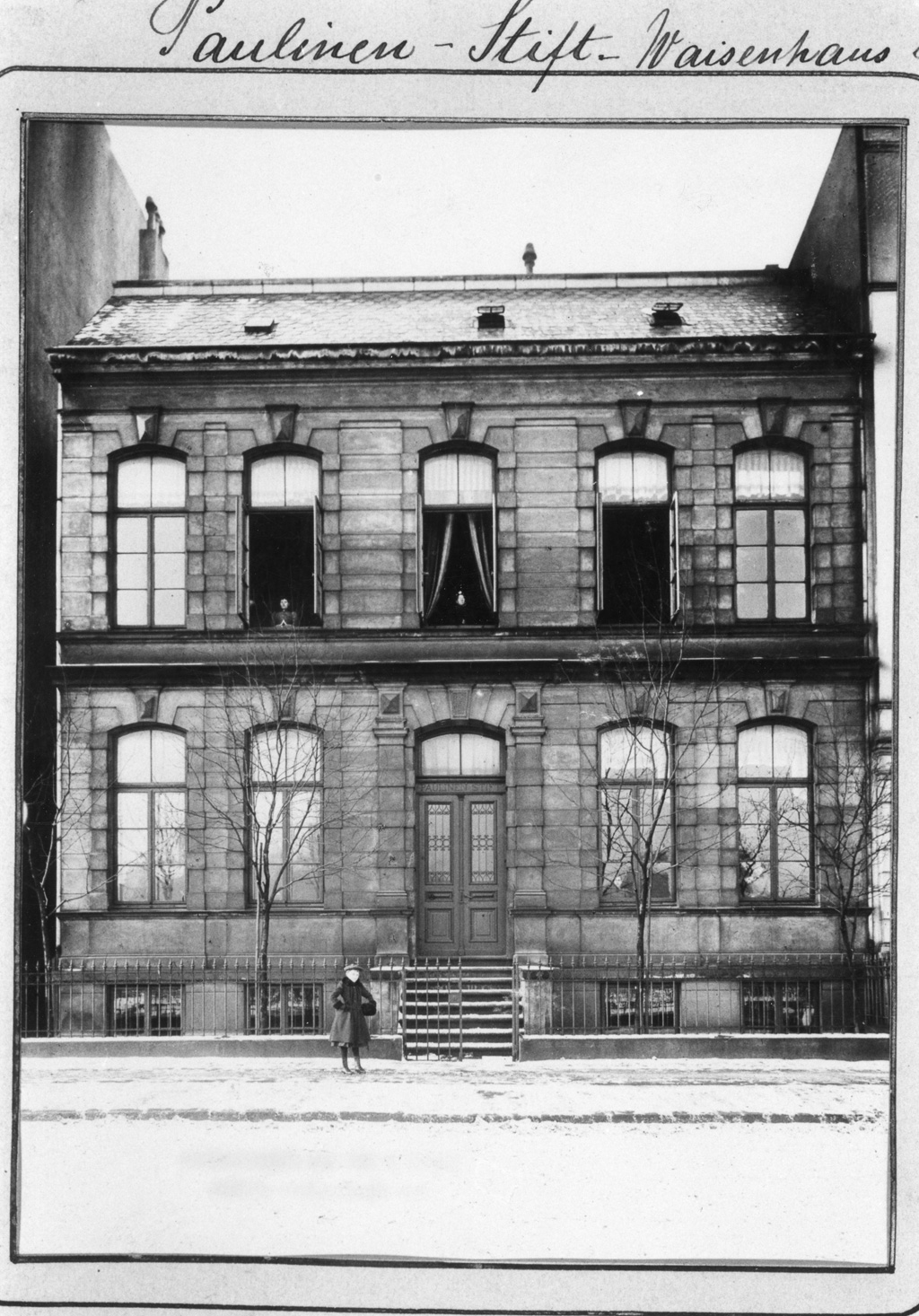

Paulinenstift for Jewish orphans, Laufgraben 37 in Hamburg, around

1937

Source: Picture Database of the Institute for the History of the

German Jews, BAU00048, private collection of Ursula Randt.

After the Emancipation Law of 1864 had both repealed mandatory membership in a designated congregation [Gemeindezwang] and codified equality before the law for Hamburg’s Jewish citizens, the parameters of the Jewish welfare system fundamentally changed as well. Municipal institutions were now responsible for Jewish charity cases as well, in fact, the state urged the shutting down of separate Jewish welfare organizations as a matter of principle. The Jewish congregation successfully insisted on maintaining them on a volunteer basis, however, and despite the state’s responsibility, the Jewish charity system was actually expanded in subsequent decades until it was able to cover all areas of life and all potential emergency situations. As in previous decades, prevention was its main strategy: health care, education and professional training in children’s homes, vocational placement, and loans were all meant to prevent destitution in the first place. In this regard they were often recognized as models for similar Christian or non-confessional institutions in Imperial Germany, with whom they cooperated successfully in many areas.

Notwithstanding the parallels to its non-Jewish counterparts, welfare, whether traditional or modern, always had an additional and quite controversial meaning for the Jewish community. For welfare was not merely a preemptive measure to prevent social hardship, but also to defend against prejudice and hostility. It was no coincidence that those who received support also belonged to the groups who might provide a target for antisemitism: in the first half of the 19th century it was Jewish peddlers or the abovementioned “street beggars,” while trafficking of girls and prostitution became the main focus of later decades. When the communities in 1880 began to take care of eastern European Jews emigrating from the port of Hamburg, their goal again was to transport them overseas as quietly and peacefully as possible.

The Jewish welfare system’s external function as protection (of the community overall, but also of poor individuals from potentially antisemitic state authorities) was mirrored by its internal cohesion: as explicitly Jewish institutions, most of them were governed based on Jewish religious law, offering kosher food, observing the Shabbat, and celebrating Jewish holidays. Thus they provided an attractive opportunity to become active for two groups in particular. First, to women who despite reform and liberalization were still excluded from religious life outside the home and for whom charity work therefore was an activity both religiously legitimized and compatible with contemporary gender roles. As local and therefore very visible institutions, the numerous charity organizations were also highly attractive to minor and major patrons who supported various Jewish causes through donations, endowments, and bequests, which gave them an opportunity to express their close ties to their community of origin. The community’s increasing wealth and integration into the middle class eventually made those foundations particularly attractive whose mission was to support both the Jewish and the non-Jewish poor. Therefore Hamburg’s general welfare system benefitted to a great extent from Jewish benefactors.

Oppenheimer Wohnstift (Housing Foundation),

Kielortallee in

Hamburg

Source: published in: Hamburg

und seine Bauten unter Berücksichtigung der Nachbarstädte Altona und

Wandsbek 1914. Bd. 1, hrsg. v. Architekten- und Ingenieur-Verein zu

Hamburg, Hamburg 1914, S. 342, URL: resolver.sub.uni-hamburg.de/goobi/PPN639579191_1914_1, provided

by the State- and University

Library Hamburg Carl von Ossietzky, CC BY-SA

4.0.

After World War I this system underwent a general crisis since bequests and endowments had completely lost their value due to inflation. At the same time, the number of charity cases increased so that welfare became a central matter of community life during the Weimar Republic years. In order to work more effectively, it was decided in 1924 to combine the two previously separate governing entities, the poverty commission Armenkommission and the welfare commission Wohlfahrtskommission, into one central commission. Due to increasing economic hardship, especially after 1929, it administered about a third of the congregation budget. While it was proud to have run Hamburg’s institutions according to the standards of modern social welfare for years, the congregation now felt the need to resort to earlier models of charity, for example by founding a Winter Relief Organization Winterhilfswerk which distributed in-kind donations such as coats or shoes to the poor.

Call for donation by the Jewish Winter Relief

for soup kitchen collection.

Source: Gemeindeblatt der

Deutsch-Israelitischen Gemeinde zu Hamburg, 1937-1938. Painter: Hans Rudolf

Growald; with the kind permission of Ernest G. Growald.

After 1933 the persecution measures carried out by the National Socialist state led to a dramatic worsening of the situation as an increasing number of destitute people had to be supported by continuously shrinking means. At the same time it contributed to the centralization of Jewish welfare since institutions in Hamburg increasingly had to cooperate more closely with national institutions in Berlin. Overall their policy was to keep filing claims for government support while the opportunity still existed and simultaneously expand the aid offered by Jewish self-help organizations, especially for specifically Jewish matters—such as professional re-training and emigration. Being a large and still wealthy community, Hamburg became the destination of an ever-growing number of impoverished families from small congregations in Schleswig-Holstein in the 1930s. After 1938 all of the community’s welfare institutions were dissolved and plundered with the exception of the Israelite hospital, which was put under Gestapo supervision and remained responsible for the care of so-called “mixed-blood families” [Mischlingsfamilien] even after the end of the deportations.

After the war it was members of these families who founded the first Jewish aid organization in Hamburg, the Relief Organization for those Affected by the Nuremberg Laws Notgemeinschaft der durch die Nürnberger Gesetze Betroffenen in May 1945. Initially it organized spontaneous aid for the small number of survivors by providing them with food or fuel for fires; in later years it mainly took on the legal representation of their claims for compensation. During the early years of the postwar period, further support was received mainly from Jewish organizations abroad, namely the American Jewish Distribution Committee and the British Jewish Committee for Relief Abroad. From the moment of its reestablishment in the fall of 1945, Hamburg’s Jewish congregation was a member of the Central Welfare Office for Jews in Germany Zentralwohlfahrtsstelle der Juden in Deutschland, which supplied the congregation’s welfare budget in the first years after its founding. Its all-female social workers mainly cared for poor, elderly community members impoverished and traumatized by persecution and hardship, for whom the hospital was rebuilt, and in 1958 a nursing home was established for them which remained open until the 1990s. Caring for children and teenagers was also considered particularly important. Summer camps were organized and in the 1960s a day care center was opened, but it was closed in 1979. The wave of immigration setting in after 1990 posed new challenges to the communities’ social institutions, yet it also created new opportunities: in the years after 2000 a day care center and later a Jewish school were (re-)established, financed partly by the government and partly by Jewish organizations and foundations in the United States such as the Women’s International Zionist Organization, Chabad or the Lauder Foundation, all of which are also active in social causes in Hamburg.

This text is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the work is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute the material in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Stefanie Schüler-Springorum (Thematic Focus: Social Issues and Welfare), Prof. Dr. phil., has served as Director of the Centre for Research on Anti-Semitism at the TU Berlin since 2011 and has represented the Technical University Berlin within the Council of Directors at the Centre of Jewish Studies Berlin-Brandenburg since 2012. She held the post of Director of the Institute for the History of the German Jews in Hamburg from 2001 to 2011.

Stefanie Schüler-Springorum, Social Issues and Welfare (translated by Insa Kummer), in: Key Documents of German-Jewish History, 22.09.2016. <https://dx.doi.org/10.23691/jgo:article-212.en.v1> [February 23, 2026].