By no means without controversy, the first Jewish congregations were established in West Germany immediately after the end of the war, including in Hamburg in the summer of 1945. However, it was to take several decades before Jewish life in Germany could become a matter of course – both for the Jews living there and for the non-Jewish majority society. How fragile the relationship was, and still is, can be seen in the very slow development of a permanent infrastructure as well as in the persistent antisemitic attitudes among the population. Jewish life was given a boost by the immigration of so-called quota refugees [Kontingentflüchtlinge] from the former Soviet Union in the early 1990s. This demographic change has presented the Jewish congregations with a variety of challenges and at the same time contributed to a (religious) pluralization.

Providing a more nuanced insight into contemporary Jewish life and depicting its rich facets was one reason for the relaunch of our online exhibition “Jewish Life since 1945,” which was originally published in the summer of 2018 as the first online exhibition to grow out of the Key Documents source edition. Looking back, we can say that it successfully established the “online exhibition” format as an integral part of the source edition and at the same time, it heralded a thematic focus that we have been able to expand through further Key Documents contributions. The topic of contemporary Jewish history has by no means lost any of its relevance since 2018, the current discussions in Hamburg about how to deal with the past and (Jewish) heritage are an indication of this. While the first exhibition focused on former Jewish Hamburg residents, the relaunch expands the complex network of relationships to the (former) home by including the perspective of remigration. In order to understand the plurality of Jewish congregations, we are also taking a closer look at later migration movements. The fact that we had to update the chapter titled “Antisemitism and Hostility towards Jews” points to the fragility of the “new self-evidence” of Jewish life and once again underlines the topicality of our relaunch. As usual, the exhibition is divided into seven chapters (vertically), which deepen individual topics in horizontally arranged stations. Since this is a relaunch, you will find references within the exhibition to stations of the original exhibition, which is not replaced by the new version, but continued and expanded.

At the end of the war, only a few Jews or those persecuted as Jews had survived the Nazi terror on German territory, and many of them tried to leave their former homeland. This was especially true of the foreign citizens who had become Displaced Persons, most of whom emigrated to Palestine or the USA. At the same time, there were Jews abroad who returned to Germany, either temporarily or permanently. For Hamburg, internal congregation statistics show that these were initially isolated cases, with 23 returnees documented for the years 1945 to 1948. It was not until the 1950s that the number of returnees began to exceed the number of emigrants. The reasons for returning could be manifold and ranged from health problems due to an unfamiliar climate to legal (reparation matters) or professional motives. And the return was not always successful. The biographies presented in this chapter highlight the complex and often contradictory relationship to the (former) home, in this case the city of Hamburg.

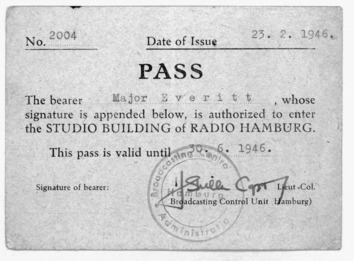

After the end of the Second World War only few Jewish men and women returned from exile to Germany. The same is true for the media sector which was to be newly organized under the supervision of the respective Allied occupation forces after the collapse of the “Third Reich.” Walter Albert Eberstadt (1921–2014), son of Jewish parents and a former student at Hamburg's Johanneum school, was one of the few Jewish returnees who participated in the rebuilding of German radio broadcasting. Eberstadt's access pass issued on February 23, 1946 illustrates that he was a so-called “returnee in uniform,” i. e. a refugee who came back to Germany as an employee of the British occupation authorities. Read on >

Published on November 24, 1957, the article is several columns long and includes a picture of Bernstein. It tells the life story of this Hamburg citizen who in the interwar years had risen to become one of the most successful shipping company owners in the Weimar Republic through his business, Arnold Bernstein Shipping Company, LLC . After the National Socialist takeover in Germany, he was robbed of his entire assets and imprisoned; after spending two and a half years in prison, he managed to emigrate from Germany to the United States in 1939 shortly before the beginning of the war. To the author of this article, Bernstein's efforts to found a U.S. shipping company named “American Banner Lines” symbolize his will to succeed and to live, as the article's subtitle demonstrates: “Former major Hamburg shipping company owner also makes it in New York.” Read on >

Arnold Bernstein in the first Online-Exhibition >

After the war, Berendsohn sought to return to Hamburg University or at least have his pension claims acknowledged. However, he met with strong resistance by leading members of the literature department. Hans Pyritz in particular agitated against Berendsohn, who had devoted himself to exile literature, by questioning his academic achievements, for example. Another argument brought to bear against Berendsohn was that he lacked a Ph. D., his degree having been revoked by the Nazis. Thus the Hamburg academics had actually strategically used a Nazi crime to make their point. Berendsohn’s “two expulsions” show the continuity of a hostile German mindset at Hamburg’s humanities department regardless of political changes. Read on >

Walter A. Berendsohn in the first Online-Exhibition >

After she had witnessed liberation by the Allies in the Mauthausen concentration camp near Linz (Austria), Esther Bauer returned to Hamburg. The British occupation authorities allocated her a room in her parents’ former apartment at Woldsenweg 5 in the Eppendorf neighborhood. Yet the man who had moved into the apartment when Esther's family had to move into a so-called “Jewish house” in 1940, a Dr. Schwarke, still lived there. Given this unacceptable situation, Esther left Hamburg and soon afterwards emigrated from Germany to the United States. (Text: Lena Langensiepen)

Esther Bauer in the first Online-Exhibition >

Max Brod is one of the German-speaking Jewish writers whose works are no longer known to many readers today. Having long been perceived mainly as Franz Kafka’s executor, who made great efforts to preserve Kafka’s work, Brod’s own texts have been receiving greater attention from literary scholars in recent years. As the typescript of Harry Goldstein’s “Address on the Occasion of the Reception of the Poet Max Brod in the Community Hall on October 16, 1954” with handwritten annotations makes clear, his visit to Hamburg a few years after the Shoah and after the reestablishment of the congregation was perceived as a great honor. Goldstein emphasized that the small Jewish community in Germany had become “destitute of people who could give it a spiritual foothold.” In Brod he saw a person who was capable of doing so; for Goldstein he was part of the “triumvirate whose brilliance illuminates our congregational life,” a triumvirate consisting of Leo Baeck, Martin Buber, and Max Brod. Both the famous Rabbi Leo Baeck and the religious philosopher Martin Buber had visited the Jewish congregation in previous years. The address testifies to the community’s difficulties in the postwar period, struggling not only for their material, but also for “spiritual existence.” Visits such as that of Max Brod represented an important acknowledgment of the congregation’s work.

At the end of 1984, director Peter Zadek, who had returned to Germany from exile in England in 1958, presented his production of the play “Ghetto” by the Israeli playwright Joshua Sobol at the Deutsches Schauspielhaus. The musical-like play about the Nazi era was very well received by the German press and theater audiences. In Hamburg, however, there were negative reactions to it as well. In self-designed leaflets like the one shown here, some of which he distributed personally in front of the Schauspielhaus as a “provocation for discussion,” the writer and painter Arie Goral criticized the portrayal of Jewish suffering and Jewish resistance as kitsch and a falsification of history. In particular, Goral felt the participation of numerous Jewish artists (in addition to Sobol and Zadek, these included Michael Degen, Esther Ofarim, Giora Feidman and Otto Tausig, among others) was anathema to him as a Jew who had fled from National Socialism to Palestine. The public discussion demanded by Goral took place on December 14, 1984 without Zadek and artistic director Niels-Peter Rudolph. Basically, the criticism of “Ghetto” raised the question what kind of artistic treatment of the Shoah is legitimate and who is entitled to make which statements – especially in post-National Socialist Germany. This episode was part of Arie Goral’s tireless struggle for a conscious and critical approach to German and Hamburg history. Incidentally, while Peter Zadek reports in detail about the work on “Ghetto” in his memoirs, he does not mention Arie Goral and his flyers at all. (Text: Sebastian Schirrmeister)

At the end of the war there were about 15,000 German Jews on German territory, several thousand of whom had survived in hiding. Most of them had managed to survive because they lived in a so-called “privileged mixed marriage” [„privilegierte Mischehe“] (if the wife was Jewish or if the children were raised as Christians), which protected them from deportation in most cases. About 9,000 Jews who had survived ghettos and imprisonment in a concentration camp outside Germany or in the German-occupied territories such as Theresienstadt returned as well. In addition, there were Jewish Displaced Persons (DP) from eastern Europe, whose number was 53,000 in September 1945. The number of Jewish DPs on German territory grew further, and they came to constitute the largest Jewish group on German territory after the end of the Second World War, concentrated mostly in American-occupied Bavaria. In northern Germany, Bergen-Belsen was the largest center. For most of these DPs Germany was no more than a transit stop. Yet not all of them actually immigrated to the state of Israel founded in 1948 or to the United States. Many remained in Germany, where they founded the first new Jewish congregations. However, the wish to emigrate often continued to persist for a long time. In Hamburg there were 647 Jews after the end of the war in 1945, almost all of them part of a “mixed marriage.” A further 50 or 80 individuals had survived persecution and war in hiding or by assuming a false identity. (Source: Introductory Text: Demographics and Social Structure)

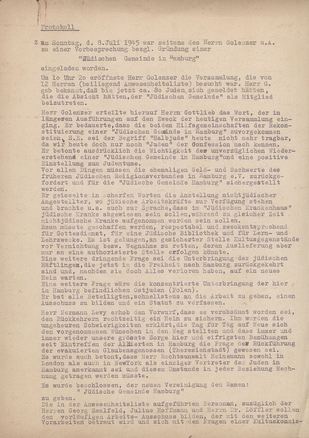

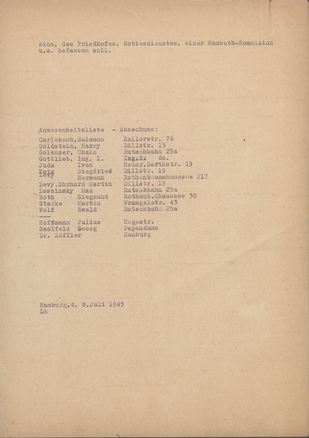

On July 8, 1945, a Sunday, twelve Hamburg Jews gathered in the apartment of Chaim Golenzer at Rutschbahn 25a, a so-called “Judenhaus,” with the intention to reorganize the congregation that had previously been eradicated by the National Socialist regime. They were all former members of Hamburg's German-Israelite Congregation. The meeting was opened by Josef Gottlieb, who had probably initiated the founding of a new Jewish congregation in Hamburg. However, those present were not the only ones interested in a reorganization of the former congregation. The meeting's minutes of July 8 mention roughly 80 Jews who had “been in touch.” Read on >

Three years after the end of Second World War, on September 13, 1948, Heinrich Alexander, a Berlin Jew who survived the war in emigration wrote this letter to the head of Hamburg’s Jewish congregation. In his brief letter he explained that he did not want to remain in Berlin and asked Harry Goldstein, the head of the Hamburg congregation to support his relocation to Hamburg. A couple of weeks later Goldstein replied. In his letter Goldstein explained that because of the housing shortage and the difficulties to receive a residence permit for Hamburg he would not be able to help, and he asks Alexander to reconsider his plan. Read on >

In this letter of November 25, 1946, the board of Hamburg's Jewish congregation, which had only been formed about a year earlier, appeals to all members to participate in its religious and cultural activities. On the one hand, this document shows that the congregation had successfully established itself, on the other hand it also reveals the discrepancy between a congregation that was conceived as an Orthodox uniform congregation and its membership. Moreover, the letter illustrates that the congregation felt pressure to justify its existence both within Germany and from abroad.

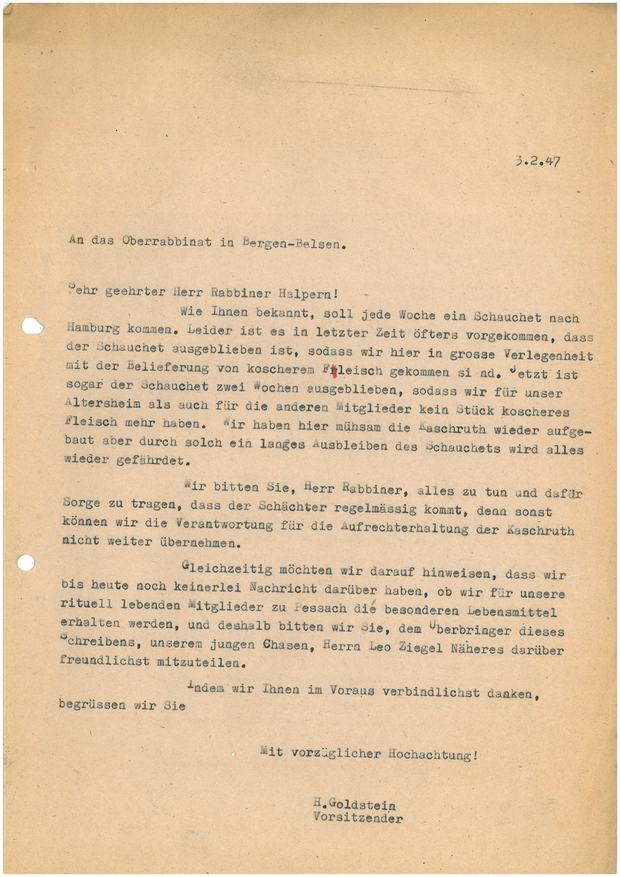

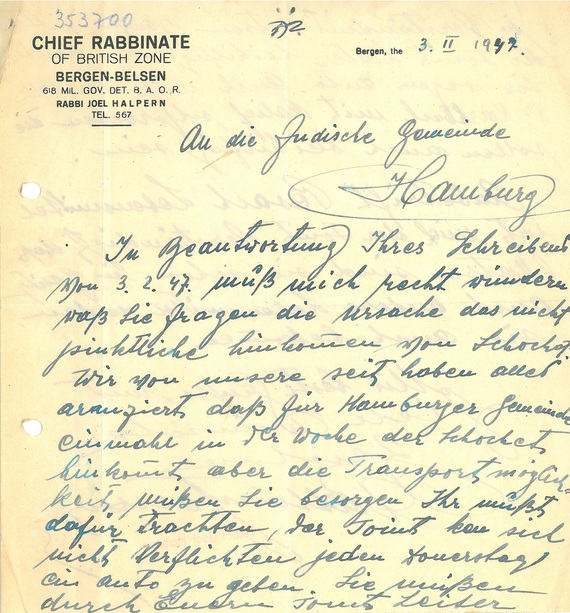

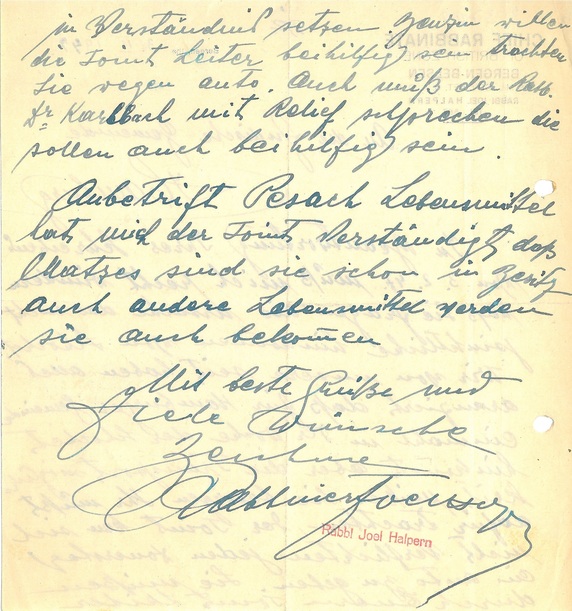

In addition to the housing shortage, the difficulties encountered in everyday life also extended to finding (kosher) food, including kosher meat. As Rabbi Joel Halpern, member of the Council of the Chief Rabbinate of British Zone, explains in his reply to the chairman of Hamburg's Jewish congregation, Harry Goldstein, a shohet carrying out kosher butchering was available to the Jewish congregation once a week. Kosher butchering, or shechita, had only been permitted again in Hamburg in March 1946. The mayor's notice to this effect included the condition that as little pain as possible must be inflicted on the animals. The correspondence also shows how difficult it was to organize the shohet’s travel from Bergen-Belsen to Hamburg and the role aid organizations such as the American Joint Distribution Committee or the British Relief Unit played in providing for Jewish communities in postwar Germany. Both organizations soon expanded their support of Jewish DPs to include German-Jewish survivors and the fledgling Jewish congregations as well.

The image shows Austrian-German Jewish actress Ida Ehre, who founded the second Kammerspiele theater company in 1945, leading it to become one of the major stages in postwar West Germany. Despite all the challenges arising with currency reform, she led the theater for more than four decades until her death. Read on >

Ida Ehre in the Online-Exhibition Women’s Lives >

On March 17, 1948 the cultural office of the Central Committee of Liberated Jews in the British Zone in Bergen-Belsen sent this reply to an inquiry it had received from the fledgling Jewish congregation in Hamburg, who had asked for support in establishing a youth group. The list of items the cultural office could offer to the congregation for this purpose – such as a soccer ball or four table tennis paddles – illustrates the supply shortages shaping (Jewish) everyday life.

In late 1949, Hannah Arendt traveled to Germany for four months, during which time she visited the British occupation zone in order to survey restitutable cultural assets in the cities of Hamburg, Hannover, Köln, and Lübeck. In Hamburg in particular, she found numerous collections previously confiscated by the Nazis whose legal heirs had yet to be determined.

During her trip, Arendt wrote five official reports for Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, Inc. (JCR) which were distributed to all its board members once they reached New York. These were internal communications not intended to be made public. They give an insight into the extent of Jewish organizations’ activities in dealing with the aftermath of the Holocaust and attest to the difficulty faced by Jewish advocates in their fight for the reinstatement of the rule of law and justice after 1945. Read on >

As a founding member and first chairman, Harry Goldstein (1880-1977) was a central figure in the reconstruction of community life. Goldstein’s memoirs, recorded by his son, and his estate are also important sources for early postwar history. The annual report and the photograph of the Seder evening exemplify the complex challenges: in addition to general problems such as the poor supply situation and the lack of housing, these were characterized by inner-Jewish conflicts, the confrontation with the occupying forces, and the traumatic experiences of the survivors. Goldstein presented the annual report at the election meeting of the Jewish congregation on March 14, 1946. The meeting served to prepare for the first advisory council elections in the newly founded congregation, which were to take place at the end of April. The greeting of those present was followed by an appeal to remember the many victims of National Socialist persecution. The review of the previous months points to the many provisional arrangements, the network of different actors and the urgent tasks, especially with regard to support services and the reconstruction of the religious infrastructure. The photo shows Harry Goldstein together with British soldiers during the Seder evening in April 1946. Such shared moments were contrasted by an often difficult relationship with the British occupation forces in everyday life, which, for example, was hesitant to implement the formal recognition of the congregation as a corporation under public law.

When the Jewish congregation was reestablished in the summer of 1945, everyday life was characterized by supply shortages and provisional arrangements. This also applied to community life in the initial postwar years; one of the challenges was the material (re)construction of religious and charitable institutions to provide for the members. The laying of the foundation stone for the synagogue at Hohe Weide or the construction of the Retirement Home on Schäferkampsallee represented important milestones in this area. The example of the community center on Rothenbaumchaussee illustrates the (legal) difficulties in dealing with already existing property that the congregation was confronted with. The example of the Joseph Carlebach School, which opened in 2007, points out that the congregation’s material (re)construction is a long process that continues to the present.

During the November pogrom of 1938, Hamburg’s Jewish congregation administration had been driven out of its residence on Rothenbaumchaussee; only a few days after the end of the war, Jewish survivors took possession of the building again. With great dedication they devoted themselves to providing for the suffering Jewish population, and in September 1945 the founding meeting of the Jewish congregation in Hamburg took place there. The building quickly became the congregation’s administrative center once again. The way the congregation took possession of the building again demonstrated the self-confidence of the fledgling congregation, which drew to its long tradition, dared to make a new start and was not afraid to make its presence felt in public.

The photo shows how the congregation celebrated the first anniversary of the founding of the state of Israel in 1949 with large flags. Yet the harmony depicted was deceptive. Just how conflict-ridden the relationship with Israel actually was is revealed by the restitution dispute over the congregation’s former property, which also affected the building pictured. The main rival to the Hamburg’s Jewish congregation was the Jewish Trust Corporation (JTC), founded in 1950, which had sole claim to the property but refused to allow Jewish life to begin anew in the “land of the perpetrators.” The JTC regarded the former congregation assets primarily as a source of financing for the reconstruction work in Israel. Only after tough disputes was the Jewish congregation Hamburg finally able to get the building back in 1960. Many other properties were sold or remained with their “Aryanizers” in exchange for compensation payments. (Text: Hendrik Althoff)

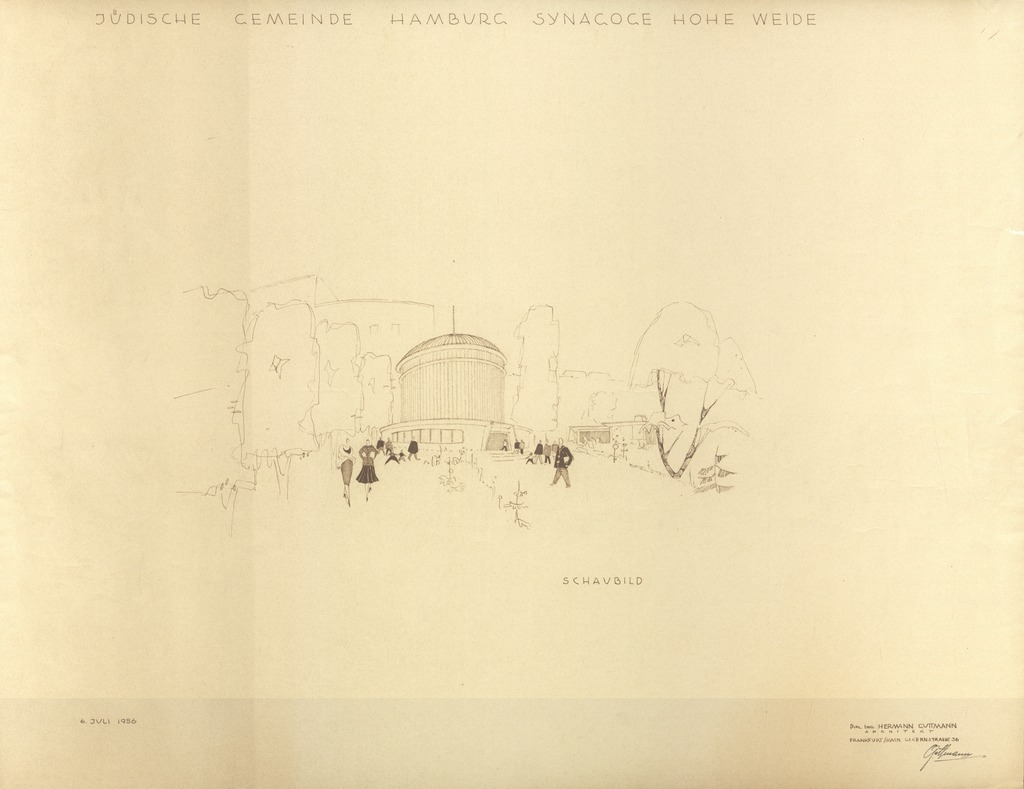

It was probably in 1956 that plans made by Hamburg's Jewish congregation, re-established in 1945, for building a new synagogue with a community center at Hohe Weide became concrete. In order to find an architect and an appropriate design, the congregation held a competition. The plan presented here is the design submitted by Frankfurt architect Hermann Zvi Guttmann. Read on >

As another central facility for basic care, the new Israelite Hospital on Orchideenstieg in Hamburg-Alsterdorf was inaugurated in December 1960. Previously, the hospital, which had been located in St. Pauli since 1843 and was donated by Salmon Heine, had been forced to move and had been provisionally housed on Johnsallee and since 1942 on Schäferkampsallee in the Eimsbüttel district. The photos show the topping-out ceremony, which took place on October 28, 1959. The three men pictured are Erik-Max Warburg, Felix Epstein and Harry Goldstein, who were members of the hospital’s board of trustees. The hospital still exists today in the same location and is open to patients of all faiths.

When the foundation stone of the new synagogue was laid on November 9, 1958, Hamburg’s mayor, Max Brauer, was present to give a speech. Hamburg’s first synagogue of the postwar period was built at Hohe Weide. Previously the small Jewish congregation had to hold prayer services in provisional prayer halls. In his speech, which was about twelve minutes long, Max Brauer commemorated the persecution and murder of Hamburg’s Jewish citizens during National Socialism and honored the efforts made to rebuild Jewish life after 1945. Read on >

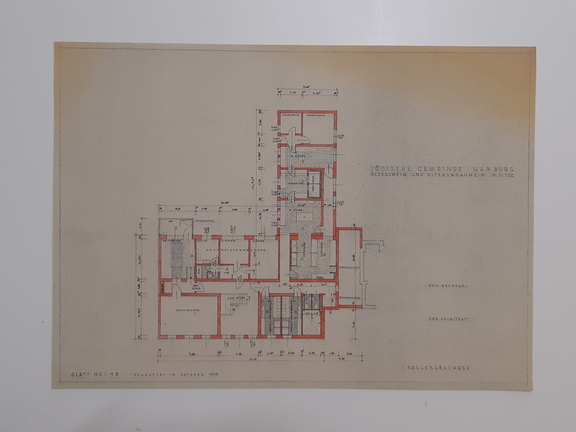

In the mid-1950s, the Jewish congregation in Hamburg, which had been reestablished in 1945, began to think about building a new home for the elderly. At the same time, their plans to build a new synagogue at Hohe Weide became more concrete. In contrast to this new building, for which the congregation announced a competition, it commissioned the architect Hermann Zvi Guttmann from Frankfurt am Main directly for the retirement home. […] The plans shown here are probably the first design plans Guttmann completed in October 1956. The set contains the floor plans for each floor, all three views and four cross sections. […] The great importance of the retirement homes points to several aspects of Jewish postwar history: First, new buildings had to be erected because the existing capacities in the restituted buildings were no longer sufficient and / or these could not be easily adapted to modern standards for structural or financial reasons. Second, many congregations also had a high percentage of older members who were unable to emigrate to another country after the Shoah to build a new life there. Others returned to Germany to spend the last years of their lives there. Read on >

In a short article, Daniel Killy reports about the opening of the Joseph Carlebach School located at Grindelhof 30, which opened its doors to 18 children attending preschool and first grade on August 28, 2007. He describes the daily routine and the concept of “rhythmicization,” meaning the multi-methodical composition of the school day at this all-day school, which follows the ideas of pedagogue Joseph Carlebach, for whom the school is named. In addition to principal Heinz Hibbeler, Killy quotes rabbi Shlomo Bistritzky, who highlights the significance of this new school for the rebuilding of Jewish life in Hamburg. Read on >

Early opinion polls carried out in Germany show that after the end of the war, antisemitic attitudes, now “privatized,” continued to exist among large segments of the population; they manifested themselves in vandalism of cemeteries, graffiti, and verbal insults. On the one hand, “post-Auschwitz antisemitism” still bears all the characteristics of “classic” antisemitism. Yet the forms it took underwent a change since antisemites now had to react to the genocide either by denial, by rejecting responsibility or by projecting guilt onto the Jews or the state of Israel. […] In the 1980s the relationship to the Jews became part of the debate in the Federal Republic about memorializing the National Socialist past, which resulted in a number of scandals and conflicts. After German unification, a new wave of xenophobic violence, neo-Nazi demonstrations, and antisemitic hate crimes occurred in the course of the debate on asylum law beginning in 1991. Meanwhile the spread of antisemitic attitudes among the population hardly changed at all. Yet antisemitism since the 1990s was not limited to the extreme right-wing fringes. (Source: Introductory Text: Antisemitism and Persecution)

In early 1957, Hamburg timber merchant Friedrich Nieland distributed a 39-page brochure titled “How Many World (Money) Wars Must the Peoples of the World Lose? Open Letter to All Government Ministers and Members of Parliament of the Federal Republic.” His “open letter” consists of a collage of quotes and illustrations taken from publications by various authors, some of them obscure, some serious. Nieland joins these together by passages of his own writing in which he declares the Holocaust the work of Jews and characterizes “the international Jews” as some sort of secret government steering world politics. Both Nieland and his nationalist publisher Adolf Ernst Peter Heimberg were charged with anti-constitutional acts and libel, but a full trial was never held. In 1959, the brochure was confiscated by the Federal Court of Justice (BGH) due to its seditious content. Read on >

Following the defacing of the Cologne synagogue with swastika graffiti during the night of December 24, 1959, which was widely reported by the media at the time, a number of copycat incidents occurred all over the Federal Republic of Germany – including in Hamburg. The police report of February 1960 lists 74 cases alone up to that date, which included antisemitic slurs and swastika graffiti in public places. These photos from the Conti Press archives show doorbell panels at Bellealliancestraße in the Eimsbüttel district; names assumed to be Jewish have been defaced by swastikas.

As a consequence of these incidents, in summer 1960 a draft law against demagoguery, which had existed since the Nieland case and was thus also referred to as “Lex Nieland,” and a revision of the statutory offense of displaying unconstitutional symbols were passed.

Street Polls on Antisemitism in the Federal Republic of Germany (NDR Retro, in German): 1959 | 1965

The study “Sephardic Jews on the Lower Elbe” published by Franz Steiner Verlag in 1958 as volume 40 of their supplement to the academic journal Vierteljahresschrift für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte (edited by Hermann Aubin) may be considered a central contribution to Hamburg’s Jewish history of the early postwar period. Its author, Hermann Kellenbenz, was one of the most influential German economic historians of his generation. In his 600-page book, he studied the economic significance of the Sephardic Jews who were expelled from Spain in the early 16th century and had been allowed to settle in Hamburg. However, the publication’s origins date back to the National Socialist period, when Kellenbenz had received a research assignment by the Reich Institute for the History of the New Germany. This fact is omitted in the study’s preface – which is hardly surprising for this time period. Read on >

In the spring of 1964, Helmut Schmidt, Social Democrat and Senator for Interior Affairs in the city state of Hamburg, who also served as a board member to the Society of Christian-Jewish Cooperation in Hamburg, learned that the local Protestant church was engaged in missionary work among Jews. This was cause for concern for both Schmidt and the Jewish community. He contacted the Protestant-Lutheran Bishop of Hamburg, Dr. Hans-Otto Wölber, personally in order to gather information on the matter and expressed his criticism of missionary work of any kind among Jews. Read on >

The aim of the project “Meet a Jew,” sponsored by the Central Council of Jews (www.meetajew.de), which facilitates encounters between non-Jews and Jews, is to counter prejudice against Jews among adolescents and young adults and to prevent antisemitism in schools, universities and sports clubs. The project, which emerged from the fusion of two educational initiatives in 2020, relies on encounters and dialogue with young Jews who, as volunteers on site, report on their personal everyday lives and answer participants’ questions. In her video statement from December 2020, Mascha Schmerling, who has been actively involved in prevention work against antisemitism since 2014 and works as one of the project coordinators, responds to the question of how Judaism can be presented and communicated in a more diverse way in the non-Jewish majority society. In order to show current Jewish life in its plurality, Mascha Schmerling pleads for a more differentiated portrayal of Jewish people and to retire the constant reference to Jewish symbols in the media or school textbooks, for example. Instead, she suggests the word “Jew” or “Jewess” should be given an individual face. According to Schmerling, this also includes allowing people to have their say who see their Jewishness as an important, but not the only facet of their individual identity(ies). In her view, it is important to make visible the breadth of Judaism as a religion, but also as a living tradition and culture.

In October 2020, a Jewish student was seriously injured by an attack with a folding spade in front of the Hohe Weide synagogue on Sukkot (Feast of Tabernacles). Although the act was very reminiscent of the antisemitic attack on the synagogue in Halle a year earlier on Yom Kippur and the attacker had a drawn swastika in his pocket, the responsible authorities did not classify the attack as antisemitic. This was a much debated and widely criticized assessment: The chairman of the Jewish congregation of Hamburg, Philipp Stricharz, for example, pointed out the necessity of naming antisemitic acts as such, for only then could they be fought. This topic also remained present at the start of the trial in February 2021. Around 25 people demonstrated in front of the Hamburg jury court holding a banner reading “Against All Antisemitism.” According to one participant, the political aspect of right-wing violence is often ignored. In the end, the court declared the attacker incapacitated and had him committed to a psychiatric clinic. According to his own statement, the victim of the crime still suffers from the consequences of the attack. (Text: Tabea Henn)

At the state press conference on April 13, 2021, the Hamburg Senate announced the appointment of Stefan Hensel, the long-time chairman of the German-Israeli Society, as the city’s new commissioner for antisemitism. This was preceded by a months-long search for a suitable personality for this office. The establishment of such an office had been decided by the citizens’ assembly [Bürgerschaft] in December 2019 as a reaction to increasing antisemitism and specifically to the right-wing extremist attack on the synagogue in Halle. In its document 21/19335, the Senate had then emphasized the “need for a state-sponsored strategy to prevent and combat antisemitism.” In addition to the commissioner for antisemitism himself, a newly established round table with representatives of the Jewish congregations, counseling centers and relevant institutions represents an important pillar of this program. In this video excerpt, Mayor Peter Tschentscher comments on the tasks and goals of the antisemitism commissioner, second mayor Katharina Fegebank explains the reasons for the establishment of this office, Stefan Hensel describes how he sees his role, and Phlipp Stricharz and Galina Jarkova point out the importance of this step for the Jewish congregations.

What does “being Jewish” mean, what role do tradition, religion and culture play for the individual as well as for the community? The stations in this chapter show that the answers to these questions are not only subject to change over space and time, but also vary from individual to individual. Very personal views of one’s own “Jewishness” are complemented by a look at communities and the commonalities that unite them: The shechita knife exemplifies the significance of common rituals, in this case those of the Persian Jews who immigrated to Hamburg since the 1950s. In the 1990s the so-called quota refugees [Kontingentflüchtlinge] changed Jewish communities not only demographically; the historical consciousness, in which May 9 as the day of victory over fascism is a central element, is exemplary for the debates that were initiated within the congregations. Finally, immigration from Israel shows that – as with all ascriptions of identity – a distinction must be made between self-perception and perception by others: Like Smadar Raveh-Kelmke, many Israelis living in Hamburg do not see themselves primarily as Jewish, but they nevertheless give a boost to the development of the Jewish community.

On September 4, 1960, the synagogue on Hohe Weide in Hamburg's Eimsbüttel district designed by architects Karl Heinz Wongel and Klaus May was formally dedicated. The video shows excerpts from private footage by Donat Horwitz, who as a young member of the congregation filmed both the laying of the foundation stone in 1958 and the opening ceremonies, which were attended by politicians and dignitaries from Hamburg. Also to be seen is the ceremonial insertion of the Torah scrolls into the synagogue’s Torah shrine (Aron ha-Kodesh) as the central religious element of the dedication. Despite various efforts, it has not yet been possible to find out where the Torah scrolls came from, whether they had already been in the possession of the Jewish congregation before the Shoah or whether they were donated to Hamburg from abroad. It is also still unclear who the persons shown are who were allowed to carry the Torah scrolls in the ceremonial procession and were honored by this task. Despite these open questions, the film material represents an important source that provides direct insights into the dedication of the Hohe Weide synagogue and thus into a significant event in Hamburg’s (Jewish) history.

In this video excerpt, Hanna and Chaim Badrian recall their wedding on January 17, 1961, which also made congregation history: they were the first couple to marry in the newly completed synagogue on Hohe Weide in Hamburg after the Second World War. Hanna was born on December 18, 1937 in Gliwice, Upper Silesia. The family managed to emigrate on the last transport organized by the Gliwice congregation. After the British occupation forces prevented them from landing in Haifa, Hanna and her parents were taken to Mauritius, where they remained interned for five years. Only after the end of the war was the family able to immigrate to Palestine. Before emigrating further to Canada, the parents wanted to show Hanna “her roots” and traveled with her to Germany, where they simultaneously fought for reparations. The family settled in Hamburg and dropped any further plans to migrate. Chaim, who was born on August 31, 1929 in Halle an der Saale, also came with his parents from Israel to Hamburg to settle reparation matters. Since reparations proved to be a lengthy and complicated process, the family got “stuck” there, as Chaim puts it. Chaim took a room on Rutschbahn, found work and met other people who had also returned from Israel, including – in 1959 – his future wife. A short time later the two were married, the wedding ceremony was performed by Rabbi Grunwald, and afterwards – as the two recall – a meal was held in the community among close family and friends.

The interview was recorded on the occasion of their 60th wedding anniversary and was made available by Raawi Magazine in the series “Raawi meets” via YouTube.

The shechita knife pictured here is in the private collection of one of the first Jewish Persians to immigrate, who had come to Hamburg from Iran in 1952, initially to trade in dried fruit and then in carpets. In the course of the 1950s, a growing group of Persian Jews immigrated to Hamburg, mostly unmarried young men who, together with non-Jewish Iranians, settled in the warehouses of the Speicherstadt district / free port to organize the carpet trade with Iran and neighboring regions from there. The success in trade led to the beginnings of a community. Persian-Jewish women came to Hamburg by way of marriage migration, and by the early 1970s there were already around 100 families living in the city, whose children, as the photo shows, also attended the Jewish congregation kindergarten. The shechet knife points to the everyday challenges Persian Jewish families faced in trying to obtain kosher meat in postwar Hamburg. Since the journey of a shochet was very costly and the centrally organized meat deliveries via the Jewish congregation did not yet exist in the early years, some of the immigrant families helped themselves by having the poultry slaughtered in their own bathrooms and making it kosher themselves. The consumption of kosher meat and Shabbat celebrations on Friday evenings, as well as feasts and holidays celebrated together, were among the shared rituals through which the Persian Jewish community cultivated its social cohesion. At the same time, the group regularly attended services at the Hohe Weide synagogue and made a significant contribution to maintaining religious community life. At times, members of the group were represented on the congregation board, while Persian-Jewish women in particular participated in social activities, such as the WIZO. (Text: Karen Körber)

This interview with Ilya Kaganovic was published on May 8, 2021 by Armin Levy in the series “Living Legends” produced for the magazine Raawi. Levy was also responsible for the interview, which was conducted in Russian and provided with German subtitles, as well as the video editing. Ilja Kaganovic, who was born on December 4, 1922, impressively describes his experiences as a Soviet soldier during the Second World War. He remembers the battles for Leningrad, Stalingrad or the Kursk Arc as well as the liberation battles for cities in Belarus, Warsaw or Danzig. He reports on a total of five wounds and numerous medals and decorations he received for his service. He concludes his remarks with the appeal not to forget the sacrifices “we had to make to free humanity from this terrible, brown disaster, this darkness.” Here, the Soviet Jews’ understanding of history becomes pointedly clear, crystallized in the significance of May 9 as Victory Day and, in contrast to the commemoration of victims, recourse to a victor’s memory that refers to the active struggle against fascism. The short video excerpt is thus also exemplary for the self-image of Russian-speaking Jews who have immigrated to Germany since the 1990s as so-called quota refugees [Kontingentflüchtlinge] and have permanently changed the Jewish communities there.

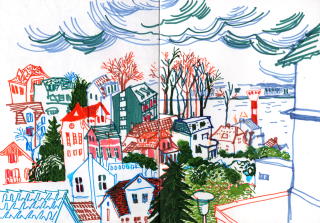

With a precise eye, the illustrator, graphic designer and Hebrew teacher Smadar Raveh-Klemke captures the surroundings in her works, be it Tel Aviv, the city of her childhood or Hamburg, her adopted home since 1981. For Raveh-Klemke, who came to Germany for love and studied at the Hamburg University of Applied Sciences, the teaching of the Hebrew language and the visualization of urban scenes are also combined in the language textbooks she has written and designed, for example in MA SE BE IVRIT, a “visual everyday journey in Hebrew,” in which Hamburg and Tel Aviv are connected in drawings. It was through her work on this book that Raveh-Klemke came to urban sketching in 2017, an international community that draws exclusively on location and publishes the resulting works online. The fact that Raveh-Klemke, who grew up in a secular-liberal family, says she identifies more with the Hebrew language and Israeli culture than with being Jewish in the religious sense, and regards herself primarily as “Hamburgerin” (Hamburg resident), is an expression of Hamburg’s diverse Israeli community, its heterogeneous self-image, the multifaceted reasons for immigration as well as the different forms of migration. According to the population register, 968 people with an Israeli migration background and 486 people with Israeli citizenship are registered in Hamburg as of December 31, 2020. Since only registered persons are included in the municipal statistics, it can be assumed that significantly more Israelis (temporarily) live in Hamburg. The Facebook group “Israelis in Hamburg,” which has existed since 2012, but which has also members who do not (or no longer) live in Hamburg, has around 1,700 members.

Religious traditions and family customs, lived in a variety of ways, can be important components of everyday life. Of particular importance is the multitude of traditions that Shabbat brings together. Shabbat is welcomed by the lighting of the two Shabbat candles on Friday evening and the chanting of the corresponding blessing, a task that traditionally falls to Jewish women. Whether Shabbat is perceived primarily as a religious commandment, an occasion to visit the synagogue, a childhood ritual, or a time-out from an accelerated daily routine, and which prohibitions and commandments are observed in connection with it, is highly individual in a pluralistic community. In her video statement recorded for this exhibition, Daphna Horwitz explains the significance of Shabbat for her and her family and the role that Shabbat candlesticks play in particular.

Various religious and social commandments are of central importance in Judaism (especially in Orthodox Judaism); they structure the personal daily and weekly routine as well as the Jewish year with holidays and fasting days. In addition to observing the Shabbat, a lifestyle in accordance with the kashrut regulations is one of the best-known commandments. Kashrut or kosher refers to the ritual suitability of (mainly but not exclusively) food and prepared dishes. This includes, for example, the division of food into dairy and meat products, which may not be stored, prepared or eaten together, as well as the ritual slaughter of animals, which follows strict regulations. A kosher kitchen also requires separate dishes, cutlery and preparation facilities. Ritually inappropriate foods are called treife. In Hamburg, unlike in other major German and European cities, it is only possible to purchase products certified as kosher to a very limited extent, as Ulrich Lohse reports in this interview. There is no facility for the ritual slaughter of animals in Hamburg. Lohse, who in the past held various offices within the Jewish congregation of Hamburg, first ran the wine shop “Mezada” and later the kosher cafeteria “Deli King” in the Grindelviertel district, but both had to close due to a lack of customers. In this interview excerpt, Lohse explains Jewish dietary rules and addresses the difficulties of kosher food supply locally. Currently, for many Jews in Hamburg, online mail order is the only way to choose from a larger selection of kosher products.

The culture of remembrance has become more diverse in recent years: it manifests itself in urban topography, in the media, and in collective and private memory. More specifically this means: statues and architectural monuments, the naming of streets, squares and buildings, memorials, memorial walls or plates, traveling and open air exhibits, public readings, decentralized plaques mounted on houses or stumbling stones embedded in the pavement, books, online articles, and events, the reading out of names, marches, and lots more. […] Since the 1980s the congregation has also been a voice in the debate about forms of remembrance in the city by criticizing the memorial at Moorweide, which did not include any information on the deportations (today there are explanatory displays), by demanding some kind of memorial for the destroyed main synagogue at Bornplatz (an artwork based on its floor plan was dedicated in 1988), and by praising the well-received sculpture in front of the former Temple at Oberstraße. […] Out of the changed culture of remembrance and the focus on the Holocaust grew a strengthened awareness of the sites of persecution and their history. Yet it also resulted in efforts to preserve the remnants of the city’s Jewish legacy without denying the significance of the Holocaust. This includes recovering existing monuments of Jewish life as well as creating a sense for the “empty spaces” resulting from National Socialist destruction or postwar urban planning. (Source: Introductory Text: Memory and Remembrance)

Contrary to the widespread view that the most recent past was not commemorated in the period immediately after the end of the war, the surviving manuscript of this speech given by Norbert Wollheim proves that events to commemorate the victims of the National Socialist policies of persecution and extermination were held as early as 1948. In his speech given on November 9, 1948 at a “commemoration ceremony on the occasion of the 10th anniversary of the beginning of the pogroms in Germany,” Wollheim addressed Hamburg's Jewish congregation, and his speech was subsequently published by the cultural office of the Central Committee of Liberated Jews in the British Zone in Germany, whose deputy chairman Wollheim was at the time.

In his speech he refers to the pogrom of November 9, 1938 as the Tisha B’Av in modern Jewish history, thus contrasting the “cruel end” with the “decades of flourishing” that preceded it. His speech is marked by a spirit of reconciliation: “Yet this is not the hour to accuse, it is the hour to reflect.” He refers to the importance of memory in Judaism and reminds his audience that the victims must be remembered.

Wollheim was actively engaged in the rebuilding of Jewish life in Germany in the immediate postwar period, and he publicly campaigned for the remembrance of Jewish victims. He came to play an important role in several court trials, especially against IG Farben.

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the 1938 November pogroms, the city of Hamburg on November 9, 1988 dedicated the “synagogue monument” designed as a walk-in space by artist Margrit Kahl (1942-2009). Located in the Grindelviertel in the Rotherbaum neighborhood within Eimsbüttel district, the monument commemorates the destroyed main synagogue of the Orthodox Synagogue Association within Hamburg’s German-Israelite congregation. It is based on designs the artist created in 1983 and 1988 that were commissioned by the city of Hamburg’s cultural office. This black and white photograph was taken by Margrit Kahl in 1988. The artist documented her work visually at various stages – during construction, at the dedication, and afterwards – and from different perspectives. The photo shown here was taken from an upper story of a building across the street at Grindelhof. It has been printed in several publications and is available online in the digital collections of Israel’s Yad Vashem World Holocaust Remembrance Center’s photo archive, while prints of it exist in the artist's estate. It documents the redesigned square including the “synagogue monument,” which stretches across an area of 35.5 by 26.4 meters; to the right, the air-raid shelter is visible; in the background several buildings belonging to the University of Hamburg are visible; not pictured here is the Talmud Torah School building adjoining the square on the left, which in 1988 was still used by Hamburg's Polytechnic School. Read on >

The Hamburg senator and SPD politician Gerhard Brandes repeatedly encouraged the city’s First Mayor, Herbert Weichmann, to establish contact with “former fellow citizens of Hamburg now residing abroad” who had been persecuted under National Socialism. Brandes, who had himself suffered persecution during the Nazi era, suggested sending New Year’s greetings and “gifts as remembrances.” Herbert Weichmann had Brande’s proposal reviewed by employees of the Senate Chancellery and subsequently rejected it. Weichmann, who was Jewish himself and had survived the Nazi era in exile, emphasized that he was sympathetic to the suggestion on a human level, but justified the rejection with administrative obstacles.

Six months later, however, Weichmann changed his mind when a former Hamburg resident living in London asked him for contacts or an invitation. In this context, Weichmann also learned that Munich and Frankfurt am Main, as well as other cities in the Federal Republic of Germany, maintained contacts with former citizens, sent them greetings through advertisements in German-language emigrant newspapers, and sometimes also invited them.

In response, the city of Hamburg published a notice in October 1965, which also appeared in the emigrant newspaper Aufbau in New York in February 1966. Invitations such as those that took place in Munich at that time were not planned at first, but only contacts by letter as in Frankfurt am Main. In his communication, Weichmann asked the former citizens on behalf of the city of Hamburg to send their addresses in order to inform them “about the political, cultural and economic developments […] in their old home town.” Based on requests for invitations that reached the Senate Chancellery in the course of the 1960s and 1970s, the city issued a few individual invitations. However, it was not until the end of the 1970s that the citizens’ assembly [Bürgerschaft] decided on an official invitation program, and from 1981 onwards Hamburg also welcomed groups of its once persecuted former residents. (Text: Lina Nikou)

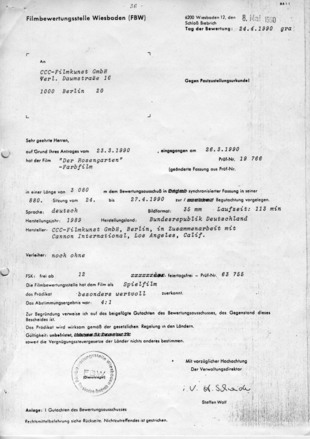

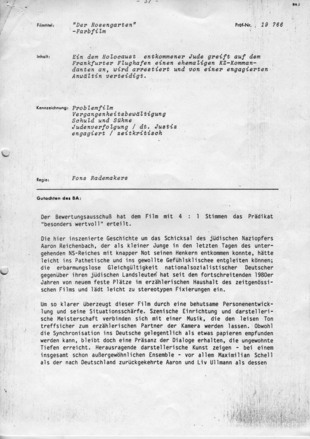

This official rating certificate for the film “The Rose Garden” issued by the German Motion Picture Rating Agency in Wiesbaden is in the collection of the German Film Institute’s Artur Brauner Archives in Frankfurt a.M. It was issued upon request on April 24, 1990. In addition to the film’s technical data such as its length (3080 m), running time (113 mins), aspect ratio (35 mm) or language (German), the document also names the company CCC-Filmkunst LLC as its production company. It is to them that this letter is addressed. According to the certificate, the feature film was given a permanent rating of “highly recommended” based on an internal vote of 4:1. The film is described as a “social issues drama” and tagged with keywords such as “coming to terms with the past,” “guilt and atonement,” “persecution of Jews,” “German justice system,” “politically engaged,” and “social criticism.” The section explaining the committee’s rating includes a brief plot summary and mainly highlights the acting, character development, and the film’s detailed observation, which the reviewers also saw reflected in the combination of image and sound. The production date, which coincided with Germany’s reunification, is seen as adding to the film’s significance because it prompted a new period of thinking in historical terms about one’s home country. First, this document can be read as a source shedding light on the trends in the culture of remembrance in Germany; moreover, the plot of this film shot in locations in Hamburg and Frankfurt also tells the story of the historic events that occurred at the school on Bullenhuser Damm in Hamburg. read on >

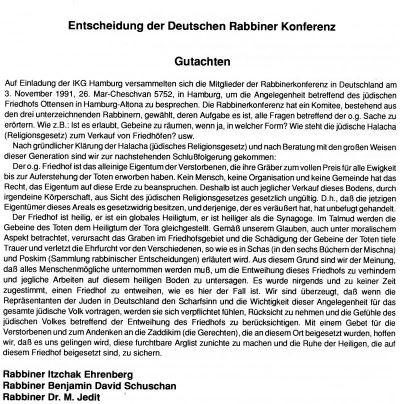

On October 28, 1661 Ashkenazi Jews from Hamburg bought a burial ground on Holstein territory in the Danish-ruled town of Ottensen. The cemetery had been established on open ground. In the course of the following decades the cemetery's location on the outskirts changed due to beginning settlement. In the Wilhelmine era it came to be located in the midst of an area of commercial and industrial use in the now Prussian town of Altona, which in 1937 was incorporated into the city of Hamburg. During the Second World War the Wehrmacht built an air raid shelter on the cemetery grounds, which destroyed a significant number of graves. In December 1942 the Reich Association of the Jews in Germany, of which Hamburg's Jewish congregation was a member by this time, was forced to transfer the property to the city as its new owner. […] Already in the summer of 1945 the congregation, reorganizing itself, demanded restitution of the cemetery site. When the city rejected the claim, the congregation brought a lawsuit before Hamburg's district court (court for restitution cases). The lawsuit was settled by a mutual agreement in 1950 / 51. The congregation and the Jewish Trust Corporation, who considered itself authorized as trustee of former Jewish assets, sold the property to the department store chain Hertie before it was restituted. A department store was eventually built on the site. […] A completely new situation arose in 1990 and the following three years. The department store chain Hertie had closed the Ottensen store in 1988 and sold the property to Hamburg property developing firm Büll & Lüdtke, who intended to demolish the existing buildings, including the air raid shelter, and erect a new shopping mall on the lot. […] When the conflict about the planned construction on the site of the Jewish cemetery in Ottensen was already in full swing, the German Rabbinical Conference in November 1991 issued an opinion. They judged the construction project as a clear violation of Halakhic law and demanded that all work on the site be halted immediately. This document represents the climax of the conflict, when battle lines were drawn between the city, the developer, and various Jewish groups whose positions were by no means unified, however, and in some cases even contradicted one another. Read on >

This exhibition emerged from a close cooperation between staff members of the Hamburg Historical Museum, the Institute for the History of the German Jews, and the initiative of former Jewish residents of Hamburg, Bremen, and Lübeck in Israel. As a first result of this cooperation, an exhibition titled “Ehemals in Hamburg zu Hause – Jüdisches Leben am Grindel” [Formerly at Home in Hamburg – Jewish Life in the Grindel Neighborhood] was shown in August 1986 in the auditorium of the former Talmud Torah School. At the time, the building was still used by the library science faculty of Hamburg's Polytechnic School. The exhibit, mainly consisting of display panels, subsequently moved to the Hamburg Historical Museum for another three months. At the same time, research and communication with lenders across the globe continued, and an inventory of Judaica existing in Hamburg museums was compiled.

(Text: Ulrich Bauche)

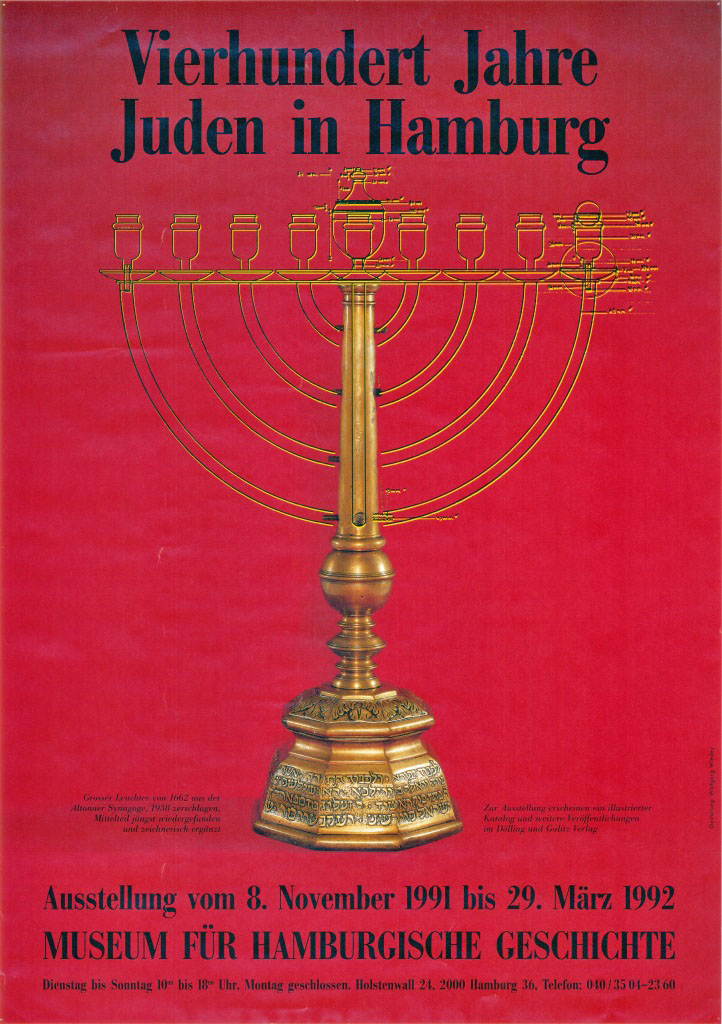

In 1989 Hebrew scholar Naphtali Bar-Giora Bamberger (1919-2000) visited the Altona Museum’s metal objects depot, where he found a broken, large brass Hanukiah menorah that until then had neither been inventoried nor documented. The octagonal, extensively molded base shows raised Hebrew writing on seven of its eight sides. According to Bamberger's translation it begins: “To honor the creator and to honor the Torah, which is our light, this Chevra has donated this candelabrum. / Our teacher and our rabbi, Rabbi Wolf from Vilna, … .” It ends: “Year 422 LFK.” According to the “Mundane Era” calculation, this dates the inscription to 1662 CE.

The twelve donors listed in the inscription could be identified as Jewish residents of Altona or Hamburg. In 1671 they were among the founders of the triple congregation association, the Hebrew abbreviation for which was “AH'U” for Altona, Hamburg, and Wandsbek. When the “Große Altonaer Synagogue” [Great Synagogue of Altona] was built in 1682 as the center of this triple congregation, it was the largest Jewish prayer house in Germany at the time. It was to be the menorah's home until 1938. The synagogue had been destroyed in 1711 in a wartime fire in Altona, during which the menorah had probably been damaged and rescued. The synagogue was rebuilt and the menorah repaired. Its central stem and the nine branches curved in a quadrant date from a restoration after 1800. When the synagogue interior was destroyed during the 1938 November pogrom, the branches were apparently broken off and subsequently lost.

Although the rediscovered fragment of the menorah represented a powerful historical object in its ruined state, curators decided to reconstruct it. The finished reconstruction is shown on this exhibition poster. The shape of the branches and candle holders could be reconstructed with the help of various photographs taken before 1938, mainly portraits of speakers at the bimah standing right next to the menorah. The museum's coppersmith and metal conservator, Karl-Heinz Budweit, created both the design sketch and the successful brass reconstruction. The new menorah measures 124 x 96 cm.

In the exhibition titled “400 Jahre Juden in Hamburg” [400 Years of Jewish Life in Hamburg] and shown at the Hamburg Historical Museum (1991 / 92), the menorah was displayed prominently and received a lot of attention. The expansive exhibition, which filled most of the galleries on the museum's ground floor, also impressed by the many objects on loan from all over the world.

This photograph shows six stumbling stones embedded in the pavement in front of the residential building at Brahmsallee 13 by artist Gunter Demnig on July 22, 2007. The brass plate-covered concrete cubes measuring 10 x 10 cm remember three Jewish couples who lived at this address: Gretchen and Jona Fels from 1920 until 1935, Bruno and Irma Schragenheim from 1927 until 1936, and Moritz and Erna Bertha Bacharach from 1937 until the spring of 1939. Demnig’s intention in placing these stones is to embed the names of the victims of National Socialism in the memory of people living today. He hopes they will start various kinds of discussions, thus continuously encouraging the study and discussion of National Socialist injustice. Read on >

On today’s Joseph-Carlebach-Platz, the former Bornplatz in the center of Hamburg’s Grindelviertel district, the main synagogue of the Orthodox Synagogue Association within the German-Israelite congregation stood from 1906 until its demolition by the National Socialists in 1939. Since the end of the 1980s, the vaulted ceiling of the synagogue has been embedded in the ground as a mosaic. The memorial, designed by artist Margrit Kahl, has been supplemented over the years by various commemorative plaques, and the square itself is central to the annual commemorative event held on 9 November.

In November 2020, the German parliament decided to support the reconstruction of the synagogue, which had previously been approved by the Hamburg senate, with 65 million euros. Since then, the form of this new building has been debated in the city's public sphere, within and outside the Jewish community – a central part of the discussion is the question of whether the new synagogue should be built as a reconstruction on its historic site. While critics fear historical revisionism and point to the significance of the empty space and the memorial, proponents see a (re)construction on the same site as a sign of the present and future of Jewish life in Germany. According to its own information, the campaign “No to Antisemitism, Yes to the Bornplatz Synagogue” has found 107,000 supporters until today.

Parallel to this, another site of Jewish urban history and how it should be dealt with in the future is being discussed: The ruins of the temple on Poolstraße, for whose preservation the initiative Tempelforum was founded.

Both examples point to general questions of how to deal with material heritage, and which traces of the past are and should remain visible in urban spaces? Questions that are important far beyond Hamburg.

Jewish life in the 21st century is characterized by a visible diversity. The various migration movements of Persian, Soviet and Israeli Jews in recent decades have increased both the religious and cultural diversity of the Jewish community. Today, Jews in Hamburg also have the opportunity to pray in the uniform congregation according to both the Orthodox and, since 2016, the Reform rite. With the Star of David congregation, there is also a liberal community of worshippers outside the uniform congregation. The following stations shed light on the various offerings and developments that contribute to a growing diversity. Among them are the previously mentioned synagogues and their worshippers; the first Reform Bat Mitzvah after the Shoah, which was celebrated in June 2021, represents an example of this. Offers for children and youths, such as the dance and song competition Jewrovision organized by the Central Council of Jews in Germany, or the chocolate seder evenings, in which the congregation teaches Jewish holiday traditions in a playful way, contribute to celebrating one’s own Judaism in different ways. Another example is the Jewish Salon at Grindel, founded in 2008, which offers a space for reflection and discussion in Hamburg with its cultural program of Jewish literature, music, art and philosophy. Contemporary Judaism in its various religious, cultural and traditional facets is also increasingly present in the city’s public sphere, not least during the anniversary year celebrating “1700 Years of Jewish Life in Germany,” in the context of which numerous events have taken place in Hamburg. An opening towards the possibilities of the digital can also be observed, be it during Zoom services during the COVID-19 pandemic or online dating services that continue the tradition of Jewish matchmaking with the technical means of the 21st century.

Jewrovision exists since 2002, and in 2013 the Central Council of Jews in Germany began hosting Europe’s biggest Jewish dance and song contest in different cities. In 2018 the Jewrovision contest took place in Dresden. Prior to the event, participants produce an introduction video about their city, their congregation, and their youth center – as did the 2017 winner, the Chasak youth center of Hamburg’s Jewish congregation. During the contest, the videos are shown in addition to the actual show act.

Opened in 2008 at Café Leonar, the Jewish Salon is an expression of a diverse Jewish culture once again becoming visible. Based on the idea of the salon, it aims to provide a space for discussion and reflection. How this can be achieved in the twenty-first century and which role the time before 1933 plays in it were among the questions four students of Hamburg’s Sophie-Barat-School discussed with Michael Heimann, one of the salon’s founders, as part of a “Geschichtomat” project week.

Hamburg’s Jewish community is diverse and polyphonic. Under the umbrella of the uniform congregation, prayers are held according to both Orthodox and Reform rites. The plurality of religious movements has a tradition in Hamburg that is closely linked to the emergence of Reform Judaism in the 19th century. Orthodox services are held in the synagogue on Hohe Weide which was dedicated in 1960. The Reform synagogue, founded in 2016, does not yet have its own premises. Services and holidays are sometimes celebrated in the assembly hall of the Joseph Carlebach School, but mainly in the Jewish House of Culture on Flora Neumann Street, which is the restored gymnasium of the former Israelite Girls’ School at Karolinenstraße 35. On weekdays, the building is used as a training center for the Elbkinder daycare center. This photo shows the hall of the Jewish House of Culture including the Torah shrine. The premises are also used by the Liberal Jewish Congregation of Hamburg, founded in 2004, which is not part of the uniform congregation and whose services are also held at various locations. Most recently, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic meant numerous challenges for congregational life. Temporarily, new virtual spaces were used, and worship and holiday-specific rites and guidelines had to be adapted to the use of familiar video conferencing platforms.

Read more about holiday preparations in times of COVID-19 here.

“The Bat Mitzvah in itself is special because you are called to the Torah as a girl, as a young woman. But this Bat Mitzvah is not only special because it is an accompanying ritual for this important step, but also because it is the first Bat Mitzvah within this Reform community and thus the first in this setting after the Shoa.”

On June 26, 2021, the first Reform Bat Mitzvah after the Shoah was celebrated by the Reform synagogue founded in 2016 in the premises of the Jewish Culture House in Flora-Neumann-Strasse. Due to COVID-19, the celebration was subject to strict hygiene regulations. Jewish boys and girls become Bar and Bat Mitzvah (son / daughter of the commandment) at the age of 13 and 12, respectively. After an intensive period of learning, they are called to recite Torah for the first time in front of the congregation during the morning Shabbat service (Shacharit) and attain religious maturity in their daily lives and in religious services. Outside of Reform Judaism, Jewish girls also become Bat Mitzvah, although this is not accompanied by wide-ranging equality in the religious sense. Cantor Deborah Tal-Rüttger, who taught this girl for almost two years, referred in her speech to the importance of the Bat Mitzvah not only as a step into religious “adulthood,” but also as part of a self-determined and responsible personality formation. In addition to the meaning it has for the individual and her family, the quote from the mother’s speech of the Bat Mitzvah also ascribes historical significance to the event. Cantor and Bat Mitzvah led the service, which lasted several hours, together. The pictured “icon” for the Bat Mitzvah was designed by Hamburg graphic designer Anne Vogt according to the family’s suggestions. The internationally known dove of peace, which appears in the First Book of Moses at the end of the story of Noah, is associated with the Star of David, which represents Jewish identity and Judaism and is thus intended to be a universal symbol of peace, hope and a prosperous future for Reform Judaism in Hamburg.

The photo shows the ingredients for a chocolate seder. The Seder evening is celebrated as part of the Passover festival, which commemorates the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt and liberation from slavery. On a traditional Seder plate are six mainly bitter ingredients, symbolic of the time of slavery. The traditional foods drawn on this paper plate, sroa (bone), karpas (vegetable), charosset (sweet paste), maror (bitter herb), chaseret (cabbage/salad) and a boiled egg, were replaced here with child-friendly ingredients such as cookies, strawberries or chocolate. This chocolate seder took place in 2019 as part of the congregation’s children’s and youth programs; such events serve to introduce younger generations to Jewish traditions through play.

As part of the anniversary year celebrating “1700 Years of Jewish Life in Germany,” numerous events were held in Hamburg that focused on Jewish culture and religion in the past and present. The Jewish congregation of Hamburg used the framework of the festivities to make itself more visible to the city’s public than ever before, for example with an extensive presentation film to kick off the anniversary year, an open synagogue day, the XXL Sukkot celebration on Joseph Carlebach Square (shown in the photo), or the website juedischesleben.hamburg. Numerous initiatives and institutions participated in the extensive program. Through a cooperation of the Jewish congregation with the Abaton Cinema and the Institute for the History of German Jews, the Jewish Film Festival Hamburg, whose poster we are showing here, also took place for the first time in 2021. From August 8 to 12, the interested public was able to watch five films from different countries, which were dedicated to very different aspects of Jewish history and the present. The film festival opened with a matineed screening of the multi-award-winning short film “Masel Tov Cocktail” (2020). Beyond the anniversary year, there are numerous initiatives of Jewish culture, one example being the Jewish Chamber Orchestra Hamburg, founded in 2018 under the direction of cellist Pyotr Meshvinski (video still left). The chamber orchestra sees itself in the tradition of the Jewish Chamber Orchestra Hamburg, which was founded in 1934 by the violinist, conductor and composer Edvard Moritz and banned by the National Socialists. With its concert program “Musical Stumbling Blocks,” the ensemble aims to remember the now lesser-known works of murdered Jewish composers such as Gideon Klein, Hans Krása and Viktor Ullmann.

This dating ad was published in the Rosh Hashana issue of Raawi Magazine in September 2021. Using modern means, the tradition of matchmaking is continued here: Interested persons – the majority of whom are women – can apply. In addition to personal details and a photo, the candidate is introduced by the local rabbi. Unlike the big dating portals, the matchmaking process is not based on algorithms, but on the expertise of selected congregation members, including the wives of Hamburg’s two rabbis. The first wedding of an international couple who met through this matchmaking service has already been celebrated in Hamburg.

Conception: Anna Menny, Sonja Dickow-Rotter. Texts: unless otherwise stated: Sonja Dickow-Rotter and Anna Menny. Technical implementation: Daniel Burckhardt. Translation: Insa Kummer.

As of: November 9, 2021.

The exhibition is a relaunch of the exhibition “Jewish Life since 1945,” published in 2018 as part of the Key Documents source edition.