In early modern Jewish history the lines between science and religious learning are somewhat blurry. Rabbinical writings or polemics on religious law, for example, represent testimony of a thorough study of Jewish sources. In the course of the Enlightenment the approach to sources changed and a reflection on the method of enquiry began. Thus the two paths separated – for academic studies now claimed to be different from religious treatises both in nature and method. With the beginning of the 19th century, philological studies were separated from dominant Christian theology to become part of the discipline of Oriental studies, and Jewish sources were now studied as historical documents. It was in this context that a Wissenschaft des Judentums emerged as an intellectual movement centered in Berlin, yet there were attempts at this new kind of historical-critical study of Judaism in Hamburg as well. In order to describe the study of Judaism in the city of Hamburg and the wider region, both non-Jews and Jews analyzing Hebrew texts, publishing treatises on questions of religious law or collecting rabbinical literature need to be considered as providing evidence of learning. Polemical writings and studies as well as libraries and manuscript collections originating long before the establishment of Hamburg University in 1919 provide information on scholarly activity in the city. Traces of research carried out by non-Jews can be found in the Oriental studies and Christian-influenced Hebrew studies pursued at the Akademisches Gymnasium, in Hebrew and Arabic book printing or in the establishment of libraries and special collections. Furthermore, Hamburg has a history of Jewish learning – community libraries and private collections were set up and used in synagogues, prayer rooms and kloyzn school, Jewish schools, printing presses, book stores, and later in lodges and club houses. Moreover, controversies within Hamburg’s Jewish community about questions regarding religious law became well known far beyond the city’s limits. In the 19th century, Hamburg therefore became a hub for the now flourishing Wissenschaft des Judentums, although it had gained institutional footing there only hesitantly and later than in Imperial Germany’s other cities. This development, which marked the beginning of a growth in Wissenschaft des Judentums, ended abruptly during National Socialist rule, when scholars had to emigrate or were deported and murdered. In the years after World War II, when it became evident just how much intellectual potential had been lost, institutes were founded at universities, and short and long-term projects were carried out in order to create a new basis for research in Judaic and Jewish Studies in the Federal Republic of Germany.

One of the consequences of the expulsion of Jewish communities from the Iberian Peninsula and the conquering of Antwerp by the Spanish army in 1585 was that Sephardic scholars, physicians, and rabbis migrated to the German-speaking territories, including Hamburg and the religious sanctuaries of Altona and Wandsbek. Ashkenazi Jews, referred to as Tudescos (Portuguese for “Germans”) by Sephardic Jews, followed. Several prominent scholars were active as spiritual leaders, teachers, translators or printers in the Hamburg area, and they made the city known as a place of early modern Jewish scholarship. From the early modern age until the early 19th century, rabbinical studies were pursued in the kloyz school, a place funded by wealthy members of the congregation. The famous legal scholar Tzvi Hirsch ben Yaakov Ashkenazi served as rabbi of the Chacham-Tsvi kloyz in Altona, for example. Another pillar of religious scholarship, printing presses often expanded a city’s reputation far beyond its limits. Jacob Israel ben Tsvi Emden, son of the above-mentioned rabbi, was both a private scholar and book printer. His printing press was well-respected – Emden owned printing plates in Rashi typeface as well as square typeface, and he printed copies of his own works as well as pamphlets and rabbinical writings. His Machzor prayer book for the holy days was known beyond the region of Hamburg and was reprinted in Zhytomyr and Lviv. In addition to the establishment of teaching houses and printing presses, books owned privately or by congregations also give evidence of Jewish scholarship. Libraries could be found in synagogues, prayer halls and kloyzn school, Jewish schools, printing shops, book shops, and later in Masonic Lodges and club houses. In most cases they belonged to wealthy families collecting religious and secular books, Hebraica, and other valuable printed matter. Among these were the two largest Jewish private libraries, the collections of David Oppenheimer and Heimann J. Michaels, which did not remain in Hamburg, but in 1829 were sold for a “ridiculously” Peter Freimark, “Jüdische Bibliotheken und Hebraica-Bestände in Hamburg,“ in Tel Aviver Jahrbuch für deutsche Geschichte 20 (1991), pp. 459–467, here p. 460. low price to Oxford and London respectively. Hamburg is still home to the Levy collection, which includes a wide array of holdings such as Bible commentaries, liturgical, Kabbalistic, scientific, and medical texts as well as poetry and prose. The Hamburg Public Library acquired this collection in the early 20th century.

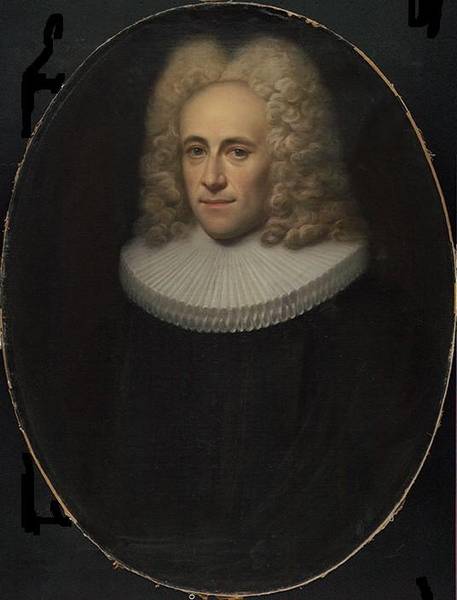

Christian scholarly institutions primarily had a Protestant, theological interest in Jewish history and literature, which was frequently based on proselytism to Jews [Judenmission]. In Hamburg there was one such school, the Hamburgisches Akademisches Gymnasium. This institution, nationally renowned in the 17th and 18th centuries, established a professorship for Oriental languages among other subjects. Its occupants, such as the collector of Hebrew literature Johann Christoph Wolf, who had taken up his position as professor of Oriental languages at the Akademisches Gymnasium in 1712, shaped local Hebrew studies.

Portrait of Johann Christoph

Wolf, unknown artist, before 1779

Source: Wikimedia Commons, public domain, provided by State and University Library Hamburg Carl von Ossietzky.

His private library, the (Uffenbach-)Wolfsche Bibliotheca Hebraea containing ca. 25,000 volumes, was incorporated into the Public Library around 1750. Its collection of richly illuminated manuscripts represents valuable historical testimony of Christian Hebrew Studies. At least during the zenith of the Akademisches Gymnasium, Hamburg was one of the centers of Oriental Studies in the German territories alongside the universities of Leipzig, Jena, Halle, Göttingen, and Berlin. Typical for Hamburg, the Akademisches Gymnasium was part of a “scholarship without a center,” “Wissenschaft ohne Zentrum.“ Rainer Nicolaysen, “Wissenschaft ohne Zentrum. Über das Ende des Akademischen Gymnasiums 1883 und den schwierigen Weg zur Gründung einer Universität 1919,“ in: Dirk Brietzke / Franklin Kopitzsch / Rainer Nicolaysen (eds.), Das Akademische Gymnasium. Bildung und Wissenschaft in Hamburg 1613–1883, Berlin / Hamburg, 2013), pp. 213–236. a decentralized network of institutions for advanced study and various collections – the Public Library, Botanical Gardens, Hamburg’s Planetarium, the Sammlung Hamburgische Altertümer, the Museum für Völkerkunde, and the Chemisches Staats-Laboratorium. Jews were barred from studying at the Akademisches Gymnasium, which prepared its students for university. Only after having converted to Christianity were they allowed to attend lectures on the liberal arts. In the 19th century the humanistic scholarly ideal of the homo trilinguis proficient in the classical languages of Hebrew, Latin, and Greek vanished: from now on Hebrew, previously a central component of theological scholarship, barely figured in Christian, modern humanistic studies. The range of subject matter narrowed as well: ancient history was now reduced to Greek history alone. Where Hebrew and Old Testament studies continued to exist at German universities, they had a missionary purpose such as the Institutum Judaicum Delitzschianum founded in Leipzig in 1880 and the Institutum Judaicumopened in Berlin three years later.

In the era of Enlightenment (Haskalah) and emancipation, Berlin became the intellectual center for German Jews. Moses Mendelssohn and his followers fundamentally changed the ideal of Jewish scholarship: the study of the Torah was no longer considered its single core, and secular subjects and European languages such as German and French became more important. Increasing attention was paid to the education of Jewish girls, although only wealthy families were able to provide it. The distribution of Enlightenment – inspired writings, pamphlets, and appeals was hindered by press censorship in all territories of the German Confederation. The communities of Altona and Wandsbek, belonging to the duchy of Holstein and therefore subjects of the Danish Crown, pursued a more liberal policy towards the Jews than Hamburg’s city assembly and the Prussian cities did, however. Thus Altona became a place of Jewish scholarship, where in 1726 a Jew was granted a printing privilege for the first time. A large share of the more than 500 Hebrew books published between the 16th and the 19th century were printed in Altona. Books printed by Israel ben Abraham Halle in Wandsbek and later in Altona were famous for their artistic design. From the 16th century until the 1820s there also were some Christians who printed Hebrew books out of humanistic motives, including Elias Hutter or Jakob and Georg Rebenlin. When censorship became stricter, the towns of Altona and, later, Hamburg became refuges upholding freedom of the press and freedom to publish – they offered alternatives for the publication of Enlightenment writings.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the historical, comparative study of Jewish tradition became increasingly dominant. It included a comprehensive review and inventory of written records as well as the establishment of Hebrew and Arabic philology as critica, i. e. disciplines in their own right. The proponents of “Wissenschaft des Judentums” advocated a historical-critical approach that understood tradition, law, and customs to be mutable and studied them as products of their historical circumstances.

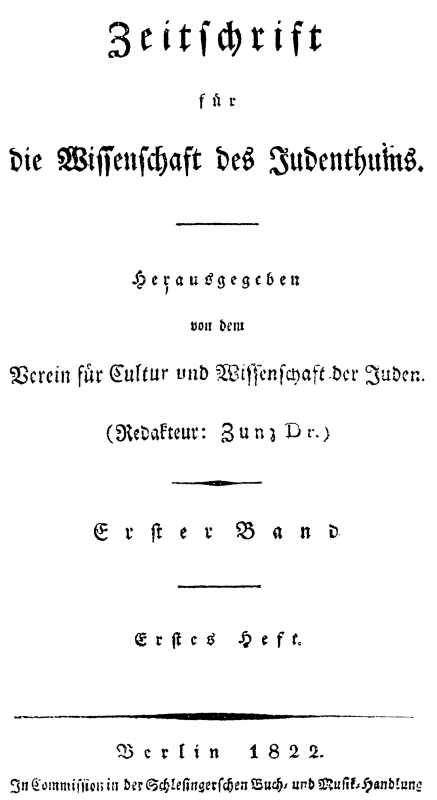

Cover of the journal “Zeitschrift für die Wissenschafts des

Judenthums”, Berlin

1822

Source: Goethe University Frankfurt, Digital Collection, Judaica, Compact Memory.

Leopold Zunz, Abraham Geiger, Moritz Steinschneider, and others attempted to establish chairs for Jewish history and literature or a Jewish theological faculty for the training of rabbis at a German university. Their efforts failed because they met with incomprehension and increasing antisemitism at the universities. Independent institutions of the Wissenschaft des Judentums were established in Padua, Wrocław, Berlin and other cities. In Hamburg a local chapter of the Akademie für die Wissenschaft des Judentums was founded. One of its representatives was pedagogue Immanuel Wohlwill, who was a teacher at the Israelitische Freischule. In 1822 he had published an article titled “Über den Begriff einer Wissenschaft des Judenthums” in the first issue of the journal Zeitschrift für die Wissenschaft des Judentums. Significant research was also carried out by Max Grunwald, who in 1898 created the Society for Jewish Folklore Gesellschaft für jüdische Volkskunde with several other ethnologists. The society’s newsletter [Mitteilungen] were published in Hamburg. Meyer Isler, member of the Wissenschaftlicher Verein and head of the Hamburg Public Library from 1872 until 1883, frequented the Berlin salons of Leopold Zunz and Isaac Markus Jost. These examples illustrate the first flourishing of Wissenschaft des Judentums, which met with interest in Hamburg, too. It reflected a general trend: numerous scholarly associations were founded and collections were expanded while the Akademisches Gymnasium in Hamburg was closed. Since the Gymnasium’s foundation, the Public Library had expanded its holdings of Hebrew, Arabic, Persian, and Ottoman manuscripts. Moritz Steinschneider oversaw the collection of Hebrew manuscripts, which had grown into one of the largest collections held by a European library. Around the same time, teaching seminars for the training of rabbis were established. Their history cannot be separated from the Wissenschaft des Judentums and the emergence of modern Jewish scholarship because discussions about the importance of Jewish tradition and its methodical study were a necessary part of a historicizing approach. The representatives of the rabbinical seminaries and the Yeshivot Talmudic college either reformed Judaism or were moderately orthodox; they simultaneously taught at universities and engaged with secular approaches. Thus the history of these seminaries is intertwined with the emergence of Wissenschaft des Judentums because scholarly activity cannot be neatly separated from religious scholarship in the 19th century either.

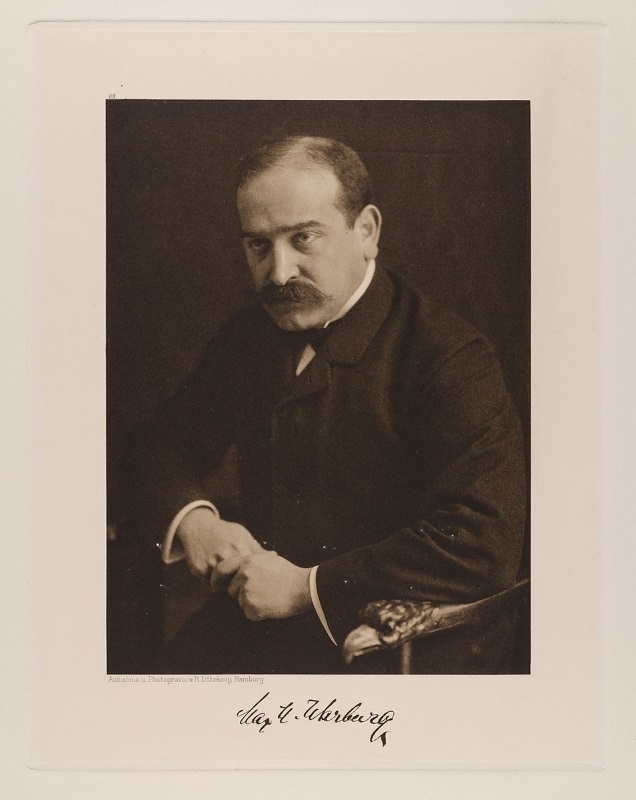

In addition to the older German universities at Heidelberg, Würzburg, Leipzig, Rostock, and Tübingen, modern reformed universities were established in the 19th century, breaking with the confessional character of the traditional university. New subjects and forms of teaching were introduced. In Hamburg’s city assembly, the “serious point of money” “der schwerwiegende Geldpunct.“ Rainer Nicolaysen, Wissenschaft ohne Zentrum. Über das Ende des Akademischen Gymnasiums 1883 und den schwierigen Weg zur Gründung einer Universität 1919, in: Dirk Brietzke / Franklin Kopitzsch / Rainer Nicolaysen (eds.), Das Akademische Gymnasium. Bildung und Wissenschaft in Hamburg 1613–1883, Berlin / Hamburg 2013, pp. 213–236, here p. 223. was the main argument against such a public institution, although interest in general lectures was growing. These lecture series were conceived for the public and were well received. It took the efforts of senator Werner von Melle to establish a university in Hamburg, however. In 1907 he and banker Max Warburg established the well-endowed foundation Hamburgische Wissenschaftliche Stiftung, thus popularizing the idea of a university founded by endowment.

Max M.

Warburg, part of the folder „Hamburg's men

and women at the beginning of the 20th century“, photographer:

Rudolph Dührkoop, 1905 (Photogravure, 21.00 x 15.50 cm)

Source: Staatliche Landesbildstelle

Hamburg, Europeana Collection, CC0-License, provided by Museum of Arts and Crafts, Hamburg.

In March 1919 Hamburg’s Social Democratic government eventually acted on a petition submitted by student veterans and resolved the foundation of a university. The 1920s saw a general trend towards consolidation at German universities, although Wissenschaft des Judentums was not acknowledged as a discipline in its own right. In 1922 Hamburg became the first European university to create a teaching position for Yiddish. Frankfurt University appointed Martin Buber as honorary professor for Religious Studies, and it assigned a teaching position for Jewish Religious History and Ethics to Nahum Glatzer. As of 1925 Berlin’s Institutum Judaicum no longer pursued a missionary purpose but instead lobbied for the academic acknowledgement of Wissenschaft des Judentums. The centers of the evolving and diversifying Wissenschaft des Judentums were Berlin, Vilna, and eventually Jerusalem: it was there that Hebrew University was founded in 1925, a research institution for a truly universal Wissenschaft des Judentums that reflected the self-concept of numerous intellectuals and scholars who saw themselves not so much as Jews, but rather as part of a religiously indifferent tradition. It was during this time, particularly in the 1920s, that the arts and sciences flourished: in Hamburg it produced the works of legal scholar Albrecht Mendelssohn Bartholdy, botanist, Zionist, and co-founder of Hebrew University Otto Warburg, and the circle of Neo-Kantians around Ernst Cassirer, for example. Physicist Otto Stern and biochemist Otto Heinrich Warburg won the Nobel Prize. Art historian Aby Warburg, an expert on antiquity and Early Italian Renaissance, considered himself “a Jew by birth, a Hamburger at heart, Florentine in spirit.” “Ebreo di sangue, Amburghese di cuore, d’anima Fiorentino,“ quoted in Werner Hoffmann, “Warburgs Konstellationen,“ in: Werner Hoffmann (ed.) Die gespaltene Moderne. Aufsätze zur Kunst, München 2004, pp. 72–79, here p. 79. The above-mentioned self-concept formed the background for Jewish scholarship until the Second World War.

German universities in the 1930s and 40s were dominated by scientific racism and the persecution of Jewish scholars. Hamburg University, Germany’s first democratically founded university, appointed many liberal and Social Democratic and even Jewish professors during its early years – a practice not common at German universities. Nevertheless the university soon noticeably shifted to the right when it expressed its support for the “national revolution” shortly after the National Socialists came to power. After the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service Gesetz zur Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums was passed, a fifth of the teaching staff were suspended for the 1933 summer semester. Among them were Social Democrat and pacifist Walter A. Berendsohn, adjunct professor for German literature and Scandinavian Studies at Hamburg University.

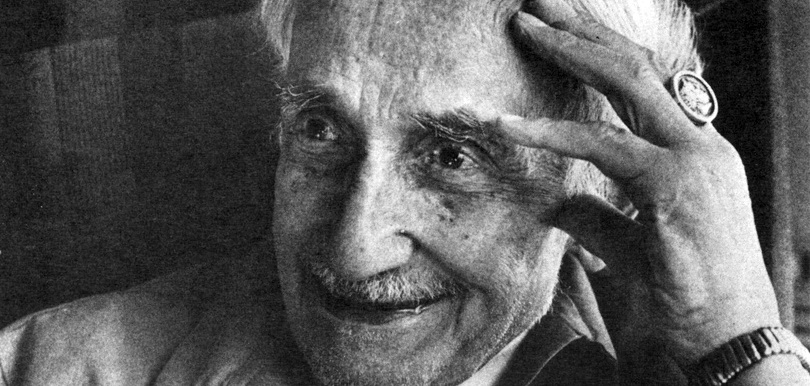

Portrait of Walter A.

Berendsohn, 1970s

Source: P. Walter Jacob Archive, Collection Walter A. Berendsohn

and Coordination Unit Stockholm, Signature: WAB/III/31.

Philosopher Ernst Cassirer, one of the first Jewish university presidents in Germany, emigrated from Hamburg to England. Erwin Panofsky is another example. The art historian had obtained his Habilitation in Hamburg in 1920; in 1935 he accepted a teaching position at Princeton University, where he became known for his revolutionary iconological approach. When the National Socialists came to power, Hamburg lost its school of art historians around Panofsky, Aby Warburg, Fritz Saxl, Charles de Tolnay, and Edgar Wind. The head of the Psychologisches Institut, Martha Muchow, was dismissed from her position as well. She was defamed as a Marxist and removed from office – the institute under the leadership of director William Stern was considered a “Jewish institute.” Faculties and disciplines were closed, and a chair for Rassenkunde [racial science] replaced the professorship for philosophy. Thus antisemitic National Socialist Judenforschung [research on Jews] also gained a foothold in Hamburg, and it did so relatively early on due to demands made by local fraternities.

Jewish Studies were established as a discipline at German universities in the years between 1963 and 1969, when institutes were founded at universities in Berlin, Cologne, and Frankfurt. In Hamburg the independent Institute for the History of the German Jews Institut für die Geschichte der deutschen Juden (IGdJ) opened in 1966 under the leadership of Heinz Mosche Graupe, beginning with the establishment of what has today become an extensive library. The institute’s research is mainly devoted to German-Jewish history.

Front view on the building Beim Schlump 83, residence of

the Institute for the

History of the German Jews in Hamburg, 2012

Source: An-d, Own work, Wikimedia Commons, CC

BY-SA 3.0.

Hamburg also became the location of further hubs in the network of research on Jewish history and culture: in cooperation with the IGdJ, the Hermann-Reemtsma Foundation funds epigraphical and iconographical research at the Jewish cemetery in Altona. The special research field “Manuscript cultures in Asia, Africa, and Europe” Manuskriptkulturen in Asien, Afrika und Europa established in 2008 also includes Hebrew manuscripts and makes them available to the public. In 2014 a chair for Jewish philosophy and religion was created at Hamburg University, and a year later an associated center for advanced studies on Jewish skepticism, the “Maimonides Center for Advanced Studies,” was opened. The diversity of disciplines traditionally based in philology and cultural history revived the Wissenschaft des Judentums at German universities. After the Shoah, Jewish Studies is eager to be perceived as a discipline in its own right and to detach itself from its previous role as ancilla theologiae. Research on the sources of Judaism no longer is the exclusive domain of theological training, as it had been well into the 18th and 19th centuries. With the study of post-biblical Hebrew, the analysis of rabbinical and mystical literature, and the study of medieval and modern Jewish philosophy, Judaic and Jewish Studies, like Yiddish Studies, managed to develop its own profile within theological, Oriental Studies, and philosophical faculties. A revival is always also a search for what has been lost: international scholarship continues to be based on the wealth of studies by Christian and Jewish scholars from German-speaking territories, well aware that these did not in fact lead to a German-Jewish “conversation” Gershom Scholem, Wider den Mythos vom deutsch-jüdischen Gespräch, in: Judaica 2, Frankfurt am Main 1987, pp. 7–11. among equals.

This text is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the work is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute the material in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Lilian Türk (Thematic Focus: Scholarship), Dr. phil., is a Research Associate at the Institute for Jewish Philosophy and Religion, University of Hamburg. Her primary research interests lie in Yiddish religious phenomenology, Yiddish language and literature, the role of the Yiddish press in social movements between 1850 and 1950, and non-conformist Jewish identities, particularly in the context of religious anarchism.

Lilian Türk, Scholarship (translated by Insa Kummer), in: Key Documents of German-Jewish History, 22.09.2016. <https://dx.doi.org/10.23691/jgo:article-226.en.v1> [February 24, 2026].