In premodern Europe, Jews, like everyone else, were able to survive not as individuals, but only as part of a group. As members of a religious minority, they especially had to create structures organizing and securing their existence. From the beginning of Jewish settlements in the German-speaking territories in the 10th century to the present day the congregation was and continues to be the central form of organization among Jews, even if its specific shape and especially its importance for Jewish life have changed dramatically over the centuries. Congregations traditionally supervised not only religious rites but nearly all aspects of their members’ daily lives such as schooling and charity or cultural activities, for example. Congregations also represented their members externally as quasi-political organizations. They were often given a certain degree of legal autonomy by local rulers or city governments, primarily with regard to jurisdiction over internal community matters. To a certain extent they were able to provide their members with protection from an environment which until well into the 19th century was mostly hostile towards Jews.

As early as the Middle Ages, various institutions indispensable for Jewish daily life emerged within the Jewish congregations, who did not form any significant networks until the 19th century. Apart from synagogues, these were schools offering religious education (Talmud schools) and ritual bath houses (mikveh). Some congregation members, usually the wealthier ones, soon began forming organizations devoted mostly to charitable causes, but also to religious rite. The most significant ones in this context were the burial societies (chevra kadisha) whose mission included ensuring that poor members of the congregation received a funeral in accordance with Jewish rites. Furthermore, in many places there were associations which awarded stipends to poor Talmud school students, provided for penniless Jews passing through their community or supported the congregation’s widows and orphans. Another important role of early Jewish associations was to support girls without means willing to marry by providing them with a dowry. Moreover, each congregation usually kept a charity fund overseen by its warden or, in the case of larger congregations, by men specifically elected to this office. In the non-Jewish premodern world, many of these tasks were fulfilled either by urban or rural community governments or centrally by the Christian churches. By contrast Jewish institutions and organizations were organized in a much less centralist manner. They were active only on the level of their respective congregation. Overall Jewish organizations not only regulated the daily life of the congregation, they also were indispensable for Jewish life in general. Where there was no religious instruction, where Jewish brides were unable to marry for financial reasons or where poor Jews were not taken care of, Jewish existence in general was directly threatened. There simply was no alternative to the Jews getting organized and looking after their own. For if Christian churches, for example, offered charitable support to Jews, they invariably sought to convert the beneficiaries.

When the first Sephardic Jews settled in Hamburg in the late 16th century, they followed the established pattern. However, the Hanseatic bourgeoisie’s religious intolerance long prevented the official establishment of synagogues. A half-century earlier a synagogue had been built, but it had to be hidden behind a residential building and could only be referred to as “meeting place” [Versammlungsort]. When the Regulation on Jews Judenreglement was passed in 1710, the Jewish presence in the city was finally provided a solid legal basis.

Many of the charitable and educational tasks among the Sephardic Jews in Hamburg were dealt with in cooperation with its Sephardic sister community in Amsterdam, where most of the families settling in Hamburg had come from. Apart from that, we know relatively little about the daily life of Sephardic Jews in Hamburg since only a fraction of sources survives for the 18th century.

The Sephardic community, which counted about 600 souls around 1660, stagnated in the 18th and 19th century.

Painting from Martin Peter

Georg Feddersen showing the Portuguese synagogue Neveh

Shalom, built in 1771, in Altona

Source: Photography: Landesamt für Denkmalpflege Kiel, Wikimedia Commons.

By contrast the Ashkenazi Jewish communities began to flourish in the Hamburg area in the last third of the 17th century and united to form the so-called triple congregation Altona-Hamburg-Wandsbek Dreigemeinde Altona-Hamburg-Wandsbek in 1671. Several decades earlier a significantly large group of Ashkenazi Jews had settled in Danish-ruled Altona. This group and the Ashkenazi Jews from Hamburg and Wandsbek now legally constituted a unit under the jurisdiction of the rabbinical court in Altona. Although all Jews were subject to considerable legal constraints which not least significantly limited their potential economic activities, Jewish life in the Hamburg area flourished in the 18th century. Outside of business transactions, there hardly was any contact between Jews and non-Jews although there never was a ghetto, a strictly defined residential area for Jews, in Hamburg. The congregations’ traditional institutions continued to regulate both the “official” and the everyday life of all Jews, who at more than 6,000 individuals at the turn of the 19th century represented almost six percent of Hamburg’s population. It was one of the largest Jewish communities in the German-speaking territories.

In the 19th century a fundamental modernization or re-orientation of community life occurred which also affected the various organizations and institutions of Hamburg’s Jews. It coincided with a doubling of the city’s Jewish inhabitants to a number of about 14,000.

The founding of the New Israelite Temple Association Neuer Israelitischer Tempel-Verein, one of the first Reform congregations in the German territories, in 1817 represented a milestone in the religious re-orientation of a minority of Hamburg’s Jews. Although it was primarily a splinter group consisting of a small part of the congregation only, namely members of the emerging early bourgeois educated middle class, this association became the incubator for other Jewish institutions and associations. Many members of the Temple Association Tempel-Verein, which integrated a German-language sermon and an organ into its prayer services in imitation of the locally predominant Protestantism, became very active in Hamburg’s Jewish civil society in the following decades. They formed other organizations, some of which were active only within the boundaries of their religion and some of which worked beyond them. A decade earlier, in 1804 / 05, a Reformed burial society had been established. This and the founding of the Temple Association Tempel-Verein were important indicators for the slow decline of the community’s traditional organizations observing a strict Jewish orthodoxy.

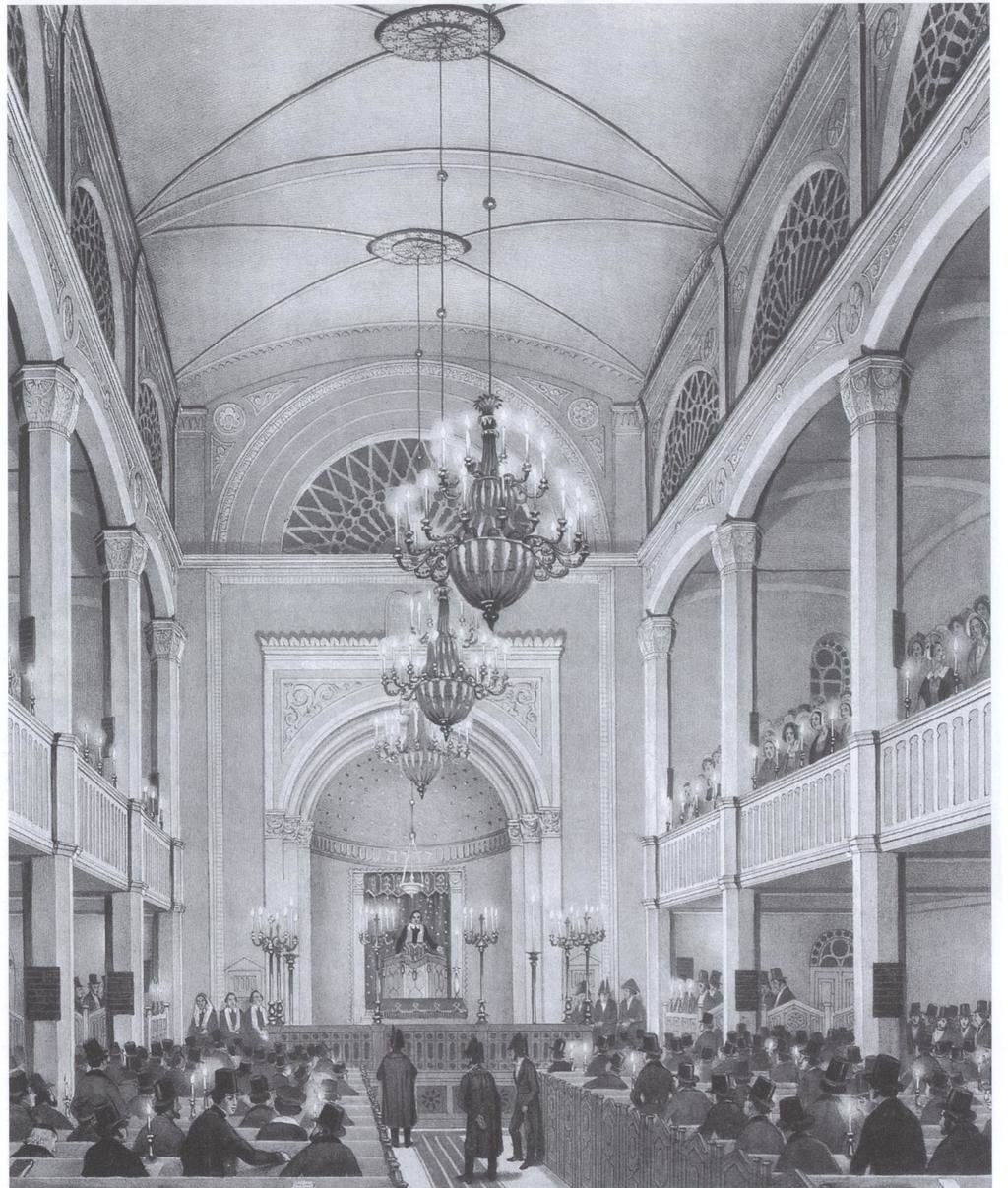

Drawing from Heinrich

Jessen of the opening of the New Israelite Tempel in

Poolstraße

on September 5, 1844

Source: Picture Database of the Institute for the History of the

German Jews, BAU00281, Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

In the middle decades of the 19th century, a large number of Hamburg’s Jewish inhabitants climbed the socio-economic ladder to join the middle class. While congregational structures remained more or less constant, these Jews created numerous new organizations for themselves which were modeled on Hamburg’s non-Jewish associations or in turn served as a model for them. Especially in the area of charity, Jewish associations were considered very efficient so that their method of operation was sometimes adopted by non-Jewish organizations. Traditional associations also continued to exist. Some of them, who represented religiously orthodox principles, continued to exist well into the 20th century, such as the youth organization “Mekor Chayim” “The Source of Life” founded in 1862, which offered the congregation’s youth a place for religious education. Yet it was organizations detached from tradition or only paying lip service to it which increasingly came to dominate and offered a growing network of non-religious options for the daily lives of Hamburg’s Jewish citizens. In one way or another, a very large part of these associations and institutions were active in the area of charity or, in more modern terms, social welfare. Moreover, Hamburg’s Jews also became organized in numerous other areas of an emerging civil society.

In the last third of the 19th century the Jews represented about six percent of the city’s total population, which not only made them the largest religious minority in Hamburg, but as such also more significant than the Catholic minority, for example. Due to their concentrated settlement in the Neustadt [New Town] quarter and increasingly in the more affluent quarters close to the river Alster, they were much more present in daily life than their number suggests. Since the middle decades of the century, many Jewish individuals had managed to rise to the bourgeois middle class, which was particularly relevant for Jewish organizational and institutional life. For the bourgeois society emerging all over Germany as well as in other European countries and increasingly dominating urban areas in particular, associations were of a significance which can hardly be overstated. Those who were part of the bourgeoisie usually belonged to a number of associations of different kinds, most of which were intended to serve the purpose of improving common welfare or providing opportunities to socialize. This included charity organizations as well as arts and cultural associations. Clubs for music, singing, and gymnastics were especially popular in the German-speaking territories. It was in this sphere the bourgeois citizen demonstrated respectability; this was where recognition could be won. Moreover, associations offered an important public opportunity for regulating social relations within the bourgeoisie, and they also served to set this segment of society apart from the lower classes as well as from the nobility.

There hardly was an area of public life in which Jewish associations were not present. Education, socializing, representing political interests, cultural programs and sports were the most important areas of activity apart from charity, which was omnipresent. The question begs to be asked what precisely made an association a “Jewish” one. In some cases these were organizations which did not exist in a non-Jewish context or only in modified form. Naturally all of the traditional associations following religious laws or needs such as those who were mainly devoted to the study of religious writings fell into that category.

Façade of the Logenhaus, Hartungstraße 9-11

Source: Picture Database of the Institute for the History of the

German Jews, BAU00362, Collection Müller-Wesemann, Zentrum

für Theaterforschung, Hamburg

The Hamburg chapter of the globally active organization B’nai B’rith “Children of the Covenant”, the Henry Jones-Lodge, only had Jewish members. An organization similar to the Freemasons, it was devoted to promoting general humanitarian interests. From this Lodge, other associations developed whose missions included promoting “Bodenkultur,” meaning agricultural work, or gymnastics among Jews. These examples show that there were numerous organizations which by no means pursued decidedly “Jewish” interests, but defined themselves as Jewish due to their exclusively Jewish membership.

Presidential office of the Henry Jones Lodge, Hartungstraße 9-11

Source: Picture Database of the Institute for the History of the

German Jews, BAU00363; Collection Barbara Müller-Wesemann,

Zentrum für Theaterforschung, Hamburg.

In the area of politics, the Zionist groups lobbying for the establishment of an independent, autonomous Jewish territory in Palestine, or elsewhere in the world according to some groups, stand out most. Since the early 20th century these groups became increasingly prominent in Hamburg, where they came into major conflict with parts of the community who strictly rejected the Zionist agenda because they exclusively defined themselves by nationality as Germans and considered any alternative national identity for Jews as an assault on their own self-identification and a threat to the integration into general society they had achieved. This was particularly true for the Central Association of German Citizens of the Jewish Faith Centralverein deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens (CV), which was not a local Hamburg institution, however, but a nationwide organization with local chapters and headquarters in Berlin. The CV was also very active in opposing antisemitic attacks against Jews and filed numerous lawsuits, for example when Jews were discriminated against in daily or professional life.

Nevertheless, traditional congregational structures still continued to exist. In some areas they had close institutional or personal ties to various associations, yet there also were organizations competing with them. When the law stipulating mandatory membership in either the German-Israelite or Portuguese-Jewish congregation was repealed in Hamburg in 1864, these two organizations theoretically no longer were anything but associations one could join or leave. While Hamburg’s Jews could be members of a synagogue only, almost all of the city’s Jewish inhabitants also remained members of one of these two congregations, only now it was on a voluntary basis. Thus the congregations did not differ legally from the numerous associations active in other fields.

In the Weimar Republic Jewish organizations in Hamburg did not change fundamentally. Yet the overall political and social climate after the First World War became more difficult for Jews. Antisemitic hostilities increasingly occurred, which in fact led to an internal strengthening of Jewish organizations. Especially the Zionist associations, who were split into different ideological camps and took their lead from nationally or internationally active associations, grew significantly in Hamburg. In Hamburg as everywhere else in Germany, the National Socialists’ rise to power in January 1933 completely changed the situation for the Jews. They were now forced to completely organize themselves separately. As of April 1933, the “Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service” Gesetz zur Wiederherstellung des Berufsbeamtentums and a series of similar decrees ordered the almost complete exclusion of Jews from a large number of professions. The vast majority of German associations and clubs followed this legislation and included so-called “Aryan articles” Arierparagrafen excluding Jews from membership in their by-laws. On the one hand, this resulted in a stronger level of organization within the numerous Jewish associations and institutions. On the other hand, however, the Jewish system was put under increasing pressure by growing hostility from its non-Jewish environment, but also by the emigration of many members of its community. In this respect the situation of Hamburg’s Jews did not differ from that of their fellow Jews elsewhere in Germany. In 1937, Hamburg’s Jews were forced to change the organizational structure of their congregations. All Jewish congregations in Hamburg, Altona, and Wandsbek were forcibly united as the Jewish Religious Community of Hamburg Jüdischer Religionsverband Hamburg. The following year, the organization’s status as a legal entity under public law was revoked, which made it subject to taxation. The same happened everywhere else in Germany. In August 1942, the Religious Community Religionsverband was finally incorporated into the mandatory organization Reich Association of the Jews in Germany Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland, whereby the last somewhat independent Jewish representation in Hamburg was dissolved.

When the “Third Reich” collapsed and Hamburg was occupied by British troops in May 1945, Jews who had survived expulsion and destruction once again had the opportunity to settle or resettle in Hamburg. Apart from the city’s Jewish inhabitants who had suvived either in hiding or thanks to a “privileged mixed marriage” [privilegierte Mischehe], Hamburg also became a magnet for many dispersed Jews, only a minority of whom were so-called “religious Jews” [Glaubensjuden]. Virtually immediately after the capitulation, survivors in the city founded three different support groups, the Aid Organization of Jews and Half-Jews Hilfsgemeinschaft der Juden und Halbjuden, the Relief Organization for Those Affected by the Nuremberg Laws Notgemeinschaft der durch die Nürnberger Gesetze Betroffenen, and Those from Theresienstadt Die aus Theresienstadt. The primary concern of their respective members was to file claims for restitution in an organized manner with the occupation authorities and thus eventually with the German administration, which was in the process of being reconstituted. In July 1945, some Jewish individuals in Hamburg began discussing the re-establishment of a Jewish congregation. The above-mentioned, non-religious organizations were partly included in this process. However, they also represented the interests of those who were considered Jewish according to the definition of National Socialist racial law but who were not religious. On September 18, 1945 a new “Jewish congregation in Hamburg” constituted itself in the facilities used by the former congregation at Rothenbaumchaussee. It was not until 1960, however, that the first synagogue was opened in Hamburg in the postwar period; it was located in the district of Eimsbüttel and also housed a community center. Until the 1990s, the orthodox, uniform congregation using this synagogue counted between 1,000 and 1,500 members. Only when Jews from the former Soviet Union migrated to the city did the number of Hamburg’s Jews organized in congregations grow to more than 3,000. In addition, there were about 2,000 Jews living in the neighboring state of Schleswig-Holstein who also fell under the jurisdiction of the Hamburg congregation. When a new community and education center was established in the former Talmud Torah School in the Grindel quarter in 2004, the community were given another center of organized Jewish life. At the same time a new, liberal congregation was founded; it only counts a few hundred members, however. The Russian influence becomes evident in the establishment of new associations such as a chess club or an organization of Jewish veterans of the Second World War, for example. Among other things, the latter is dedicated to the maintenance of Soviet war graves.

The question to what extent Jewish associations and the presence of numerous entirely or majority Jewish institutions in Hamburg – as in other German and European cities – facilitated or prevented the integration of the Jewish minority into general society before the period of National Socialism is discussed controversially in historical research. On the one hand it can be argued that Jews did the same in their organizational life as other Hamburg citizens did and thus made a significant contribution to social integration. Various organizations which initially were exclusively Jewish over the course of time opened up to non-Jewish members, although the majority of associations founded by Jews remained strongly or completely dominated by Jewish members. Naturally Jews also belonged to non-Jewish organizations. On the other hand it has to be pointed out that Jewish associations in Imperial Germany reached a number far exceeding the “needs” of a religious minority. Jewish associations virtually represented a parallel universe or at least one that went far beyond the organizational level of mainstream associations.

There was no criticism from Hamburg’s non-Jewish bourgeoisie, however. On the contrary: the Jews’ good organization was often praised and acknowledged. It was normal for a community which was generally still considered to be “different” or “separate” to have its own organizations, which overall functioned well and gave the city’s Jews respectability and a footing in the bourgeois world. Additionally, historiography has argued that for Jews in Hamburg’s bourgeois society, as in many areas in Europe, the organizations of daily life were highly significant for maintaining their Jewish identity. The reason for this was that religion and religious rituals including prayer services, weddings or funerals increasingly became less important to Hamburg’s Jewish citizens. Circumcisions, the observance of Jewish dietary laws, keeping the Shabbat, and not least marriages within the Jewish community continued to become less frequent. Just as in non-Jewish bourgeois society, secularization made significant inroads in Imperial Germany’s Jewish circles as well. For those explicitly wanting to identify as Jewish associational life offered an important alternative. Advocating for certain causes or simply spending one’s leisure time with other Jews often represented the only opportunity for many Jews to feel Jewish at all. It did not matter whether such associations or institutions were explicitly “Jewish” with regard to their respective area of activity.

This text is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the work is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute the material in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Rainer Liedtke (Thematic Focus: Organizations and Institutions), Prof. Dr. phil., is Professor of 19th and 20th Century European History at the University of Regensburg. His research interests centre on comparative European history, urban history, Jewish history, British history and the modern history of Greece.

Rainer Liedtke, Organizations and Institutions (translated by Insa Kummer), in: Key Documents of German-Jewish History, 22.09.2016. <https://dx.doi.org/10.23691/jgo:article-220.en.v1> [February 26, 2026].