Leisure and sports are two areas of everyday life in which a lot of similarities between the Jewish minority and the Christian majority existed, yet there also were a few differences. Beginning in the early modern age and influenced by secularization and the Enlightenment, Jews increasingly adopted new mainstream leisure time activities. It was during this period that a new order of time emerged in which an increasing number of people were able to choose to spend time with activities other than their occupation or housework. Jews and non-Jews alike took advantage of new choices in entertainment and education. Outside of the religious order of the time, hardly any differences remained in terms of leisure time activities by the 20th century. Sports on the other hand were an area of leisure time activities where Jewish identity had played a key role since the late 19th century, particularly for the Zionist movement. Thus Jewish sports divided into camps over this matter: the different ideological groups within German Jewry affiliated themselves with their own sports organizations in the 20th century. In the aftermath of the separation and eventual destruction of all Jewish leisure and sports organizations forced by the National Socialists, it took several decades until Jewish sports and leisure organizations were again established in Germany. More recently, a new trend is emerging particularly in the area of leisure time activities: an increasing number of specifically Jewish organizations are currently being founded.

Leisure and sports have become increasingly important in recent decades, both in the daily lives of many people and as segments of the economy and public health. Among historians interest in these topics has also grown. Questions regarding the history of people’s daily lives, their leisure time activities, and their enjoyment of or participation in sports are not easy to answer, however. Answering them for Germany’s Jewish minority is even more difficult since Jewish historiography traditionally focused on subjects of intellectual history rather than those of daily life. Recent scholarship in social history examines questions of acculturation, of confronting antisemitism or of Jewish identities, understanding leisure and sports mainly as one aspect of these questions. The study of leisure only emerged as a field of research in the 1980s and today concerns itself with historical subjects only marginally. And while general sports history is no longer limited to accounts of heroes (and their achievements) written by fans, it only partially engages with Jewish history. Finally, the very terms “leisure” and “sports” present a problem since they were first used in the 19th century yet they describe phenomena which existed long before. In earlier periods, instead of leisure one might have spoken of idle hours Muße, conviviality [Geselligkeit], recreation time [Erholungszeit] or “time off” [Auszeiten] for a special occasion such as the Karneval season, for example. Since the Enlightenment, the meaning of leisure time has changed from simply being “spare time” to a time dedicated to developing one’s personality. Thus one reads literature in order to educate oneself and contribute to the improvement of humanity. In the wake of industrialization, this originally bourgeois ideal of leisure time was applied to other segments of society as well, especially to the working class – leisure time thus became a general social phenomenon. Europe’s increasing secularization provided another background for this social change, for since the 19th century, time off work was no longer primarily filled with religious contexts. Leisure time became a fundamental category of modern industrial society and was conceptualized as a secular opposite to time spent at work which belonged to others instead of to oneself.

The term “sports” describes physical activity carried out in the form of (public) competitions, with the goal of improving one’s individual performance or simply for one’s own enjoyment. Certain activities considered as sports today such as fencing, boxing, equitation, etc. did already exist in earlier times.

At the beginning of the early modern age, people’s daily life was mainly determined by religious rite. Large parts of the day primarily consisted of work in order to earn one’s own living. The few free hours or days were structured by religious rite, for example on the Shabbat. In addition to those activities linked to religious holidays, it seems that there also were secular pastimes, however. Musical entertainment as part of wedding celebrations or a Purim Shpiel were still anchored in the ritual context. Yet Jewish families also played music at home, visited comedies or operas and paid dance instructors for lessons, all in a secular context – at least the last three of those entertainments mentioned were explicitly prohibited by the 1706 statutes of the triple congregation of Altona-Hamburg-Wandsbek Dreigemeinde AHW. Attending masked balls also remained prohibited in all Jewish congregations until the 19th century. Explicit prohibitions indicate that there was a perceived need for regulation in this area, meaning Jewish men and women apparently attended such balls or operas. While these were mainly urban pastimes, men in the country could frequent (Christian) pubs. This shows that everyday contact between Christian and Jewish men existed, yet rabbis disapproved of this form of leisure time activity as well. Towards the end of the early modern period, a growing number of Jewish men and women attended an increasing variety of entertainments outside of their community and unrelated to religious rite.

There was a similar trend with regard to travel: until the end of the 18th century, travel to another place served either a professional or religious purpose rather than that of enjoyment and leisure. The only exceptions probably were short-distance journeys to neighboring villages in order to visit relatives, for example – hardly any sources exist on such travel, however. By the 18th century, the gradual secularization of daily life extended to the area of travel as well, and consequently contacts between Jews and Christians intensified. In the 19th century, this change became clearly visible. Letters and journals show that in the course of the Jews’ assimilation into the bourgeoisie, leisure time was filled in a new, mainly secular way. For example, wealthy Jewish women from Berlin regularly traveled to spa towns where they participated in all the usual activities and were able to choose whether to stay in a guest house run according to Jewish rite or not. While their stay in a spa town was meant to serve health purposes, it also symbolized gender differences in attitudes towards work and leisure among the emerging bourgeoisie: women symbolically represented a bourgeois family’s wealth and status since they could apparently afford to exclusively engage in leisure time pursuits.

A similar symbolic status was held by the small number of Jewish women entertaining a salon. This form of sociability and educated conversation represented a new leisure time activity for a small elite of noble and bourgeois men where discussions across religious boundaries took place. In Berlin, the salons of two Jewish women, Rahel Varnhagen and Amalie Beer, became famous while Charlotte Embden, the sister of Heinrich Heine, made a name for herself by hosting a salon in Hamburg. Yet it was another form of secularized community organization which in the 19th century developed into the most successful model in middle class leisure time activity: the association. Jewish men and women enthusiastically participated in the “age of associations” (Thomas Nipperdey). Journals show that many men used the increasing number of hours at their free disposal (first among the bourgeoisie, after the First World War also among the working class) for recreation or education outside of the family, as was the case with an unmarried Jewish bank clerk in Dresden in the years between 1833 and 1837, whose case Christopher R. Friedrichs has researched. His free time during the work week was filled with walks in a nearby park with his friends, attending free concerts offered there, playing cards or pool, and frequenting a café. He also visited the synagogue, but only on the holidays. When an independent Jewish club for leisure time activities was founded in 1833, this young man was among its first and enthusiastic members. In addition to these quotidian entertainments, he continued his education by learning foreign languages in his free time.

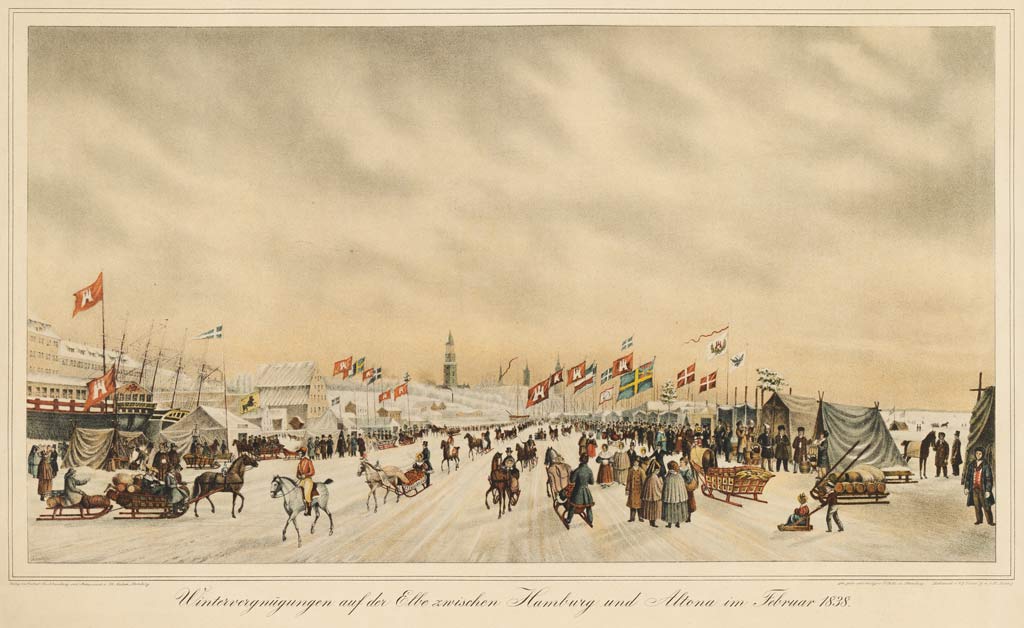

Enjoying wintertime on Elbe-river

between Hamburg and Altona, February 1838, 30 x 54 cm

Source: State- and University Library Carl von Ossietzky Hamburg,

PPN669866059, CC-License CC

BY-SA 4.0, drawn, printed and published by P. Suhr in Hamburg

- [reprint of the edition] 1838 / collotype by C. G. Röder, Leipzig. -

Hamburg: Nielsen, 1911.

The example of this man is paradigmatic for a typical way of spending one’s leisure time among men in the 19th century: recreation and education were the key elements. There was a steady increase in choices; in addition to cafés and pubs a growing number of public parks were established where entire families spent their leisure time. These public spaces could also become the location of conflicts, however, as violent antisemitic attacks breaking out in 1819 and the following years in a coffee house in Hamburg show.

The last third of the 19th century saw another increase in entertainment options: affordable books, a large selection of regional and national newspapers, classes offered commercially or by associations, clubs and associations for a wide variety of interests, movie theaters, radio broadcasts, Varieté performances, discounts on theater or opera tickets (often offered by associations to their members), as well as sports clubs and sports events (i. e. Berlin’s Six Day Race Sechstagerennen), and many more.

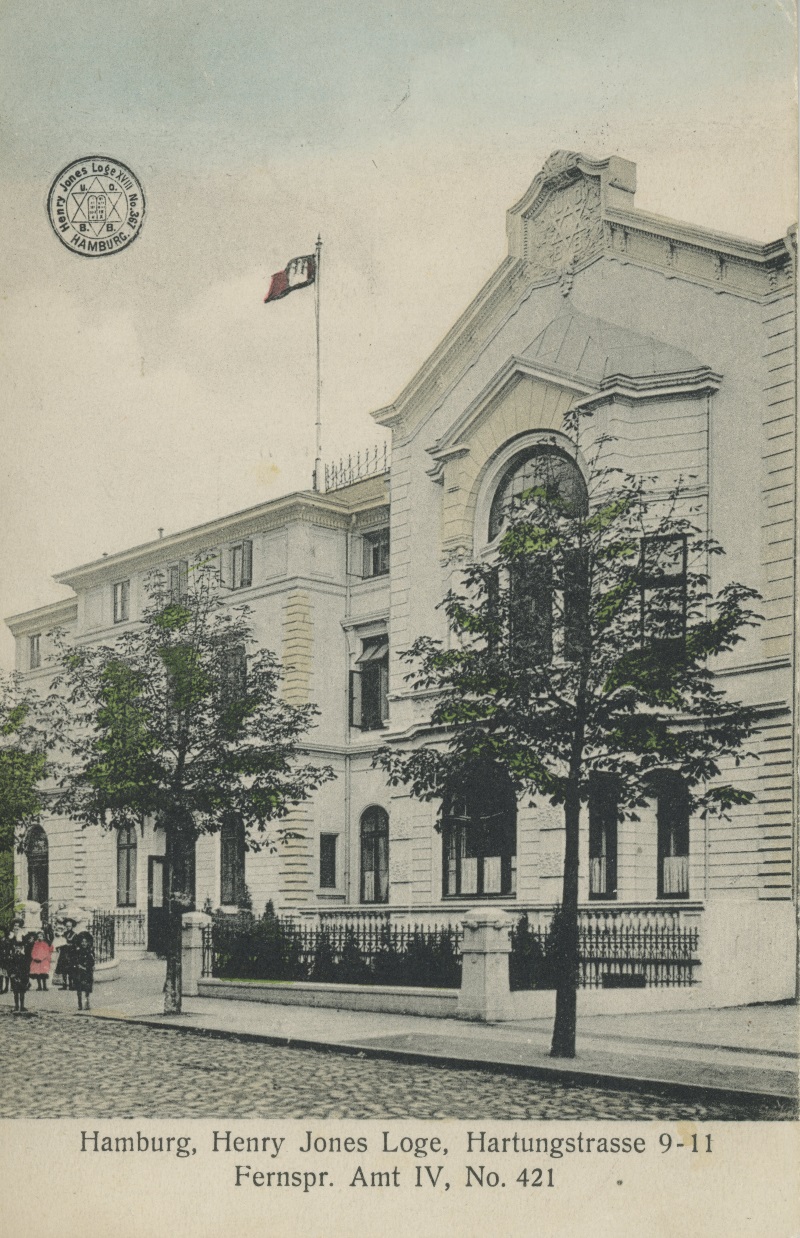

Façade of the Logenhaus, Hartungstraße 9-11

Source: Picture

Database of the Institute for the History of the German Jews, BAU00362,

Collection Müller-Wesemann, Zentrum für Theaterforschung, Hamburg

This incomplete list illustrates that free time increased among all segments of society in the 20th century, first for men, and beginning in the 1950s also for women due to the mechanization of housework and the liberalization of German society. Moreover, leisure time activities became more public, not least because of the growing commercialization of leisure. While family activities such as making music at home, going for walks and visiting relatives certainly continued to play an important role, there was a general trend towards living one’s leisure time as a sphere separate from work, family, and religion. Moreover, the emergence of the youth movement beginning in 1890 had resulted in generation-specific options for leisure time activity. Youths spent their leisure time differently than adults did, and consequently new choices were offered: first hiking trips and youth gatherings (Weimar Republic), then rock concerts and beat clubs (1950s and 1960s) and eventually youth centers run by youths themselves and party organizations for young people starting in the 1970s.

Jewish men and women also experienced this process of splitting and reassessment of leisure time. Therefore it makes little sense to look for a “Jewish approach to leisure” in the 20th century. And yet there was a particular quality, for some organizations had an explicitly Jewish identity, such as the Zionist hiking associations [Wanderbünde Blau-Weiß], for example. In the Weimar Republic in particular, numerous educational and cultural institutions such as schools and libraries were founded. The stronger antisemitism grew in German society, the more urgently leisure time associations had to find a way to respond to it. Until the beginning of the National Socialist regime, Zionist groups were a minority in Germany. Everything changed with National Socialist rule. While the state’s policy of marginalization began in professional life, it soon invaded the sphere of private life as well. Organizations aimed at aiding the Jewish community such as the Jewish Cultural Association Jüdischer Kulturbund which organized entertainment for Hamburg’s Jewish community from 1933 until 1939 / 41, often remained the only option to attend cultural events apart from the sports clubs.

Orchestra rehersal of the Jewish Cultural Association Germany at Berlin’s Philharmonic Hall

for the performances on May 7. and 8, 1934

Source: Wikimedia, CC-License CC0, family album of Dr. Werner

Liebenthal

It was during this time that Zionist ideas inevitably gained traction in Jewish society, in some cases out of pure necessity, i. e. in order to prepare for emigration, in others it was based on the conviction that this was the only possible reaction to antisemitism and that youths in particular needed to learn to show “historical awareness” in their choice of leisure time pursuits.

In the aftermath of the Shoah, new Jewish communities formed in Germany, yet they remained isolated and barely visible to the outside world until the 1980s and 1990s. The experience of the National Socialist period had also changed leisure time habits. During the years of marginalization and persecution, Jews had been forced to seek enjoyment or recreation exclusively in Jewish contexts – as long as it was still possible at all. The new congregations founded after 1945 were conceived as Orthodox uniform congregations offering relevant yet few leisure time activities in their new community centers. It seems that for many Jews living in postwar Germany, their leisure time was divided into a religiously defined sphere and a general social sphere, in which they were not necessarily identifiable as Jews or perhaps did not wish to be. When the Central Council of Jews in Germany Zentralrat der Juden in Deutschland in the 1960s pointed out that young people in particular showed little interest in community life, there were attempts to remedy this by offering special leisure time facilities such as community-run youth centers or by offering classes especially for youths. Yet all of these options were based on a decidedly Orthodox understanding of Jewish identity, which for many young people raised doubts about their own, freely chosen affiliation. Since the 1980s, these debates along with the demographic and social shifts within the communities have created a new diversity of Jewish life in Germany. Today leisure time habits among Jews do not differ significantly from those among other groups with the exception of some religious celebrations. However, there is a new development since the 1990s because some Jews now clearly show their Jewish identity or spend part of their leisure time in a Jewish context, either in a Jewish sports club or a student association such as the Jewish Organization of Northern German Students Jüdische Organisation norddeutscher Studenten e. V. (JONS) founded in 1995 or as participants in a Week of Jewish Culture, which took place in Hamburg in 2004 and 2005.

Sports has been an important part of leisure time activity since the beginning of the 20th century: a growing number of people took up sports, joined a sports club or as spectators cheered for athletes’ exceptional performances. In contrast to leisure time in general, there was a close link between sports and Jewish identity. In reaction to growing antisemitism and being banned from “German” sports clubs, yet also as part of a self-determined Jewish identity, “physical education” was declared an appropriate means to raise the new, physically strong and resilient Jew. Max Nordau coined the key term for this ideal: Muskeljude [muscle Jew]. In 1898, Bar Kochba Berlin, the first Jewish gymnasts’ club in Imperial Germany, was founded. Only a short time later, in 1902, the Jewish Gymnasts’ Association Jüdische Turnerschaft was established in Hamburg, although it did not consider itself a Jewish national association. Hamburg’s Bar Kochba club founded in 1910 on the other hand also understood its activities as a concrete, individual contribution to the creation of a modern, physically expressed Jewish identity.

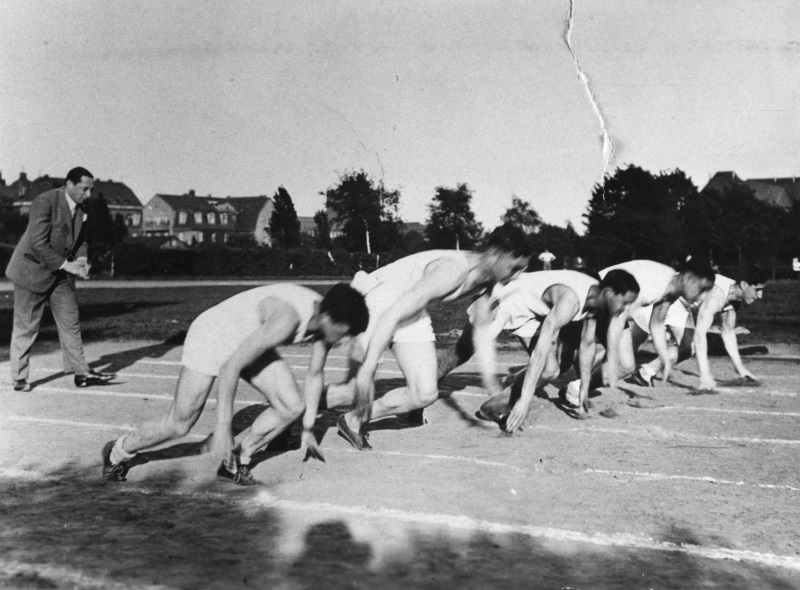

Practicing the start during running traning of Bar

Kochba in Hamburg, 1930

Source: Picture

Database of the Institute for the History of the German Jews, 21-015/319,

Collection Randt / Max Brimer.

Both clubs initially were gymnasts’ associations until new disciplines (track and field, fencing, soccer, and in Hamburg, rowing) were added in 1913 and separate women’s chapters were founded. In 1921, the Bar Kochba clubs united as the Maccabi organization, which advocated political Zionism. In this organization, athletic performance was not just linked to Jewish national pride, it also constituted an argument to refute antisemitic propaganda. At least on this issue all of German Jewry’s organizations agreed; the Central Association of German Citizens of the Jewish Faith (CV) Centralverein deutscher Staatsbürger jüdischen Glaubens only discussed sports in this respect, and it did not play a role in the organization otherwise. This is further evidence for the strict polarization within German Jewry with regard to the question of a Jewish national identity: Jewish sports were mainly a Zionist project. In Hamburg, the very founding of the Jewish Gymnasts’ Association Jüdische Turnerschaft in 1902 had been cause for criticism, as some felt it would be better to join clubs without any religious affiliation such as the General German Gymnasts' Association Allgemeine Deutsche Turnerschaft. In the 1920s, the sports movement in Hamburg became more diverse: in 1927, the Jüdischer Sport- und Turnverein Hakoah was founded in opposition to the Zionist Bar Kochba, and the Reich Association of Jewish War Veterans Reichsbund Jüdischer Frontsoldaten, which had close ties to the CV, also founded its own sports club “shield.” Sportgruppe „Schild“

Group portrait of Bar Kochba Hamburg and

Bar Kochba Kiel,Kiel, Pentecost 1932

Source: Picture

Database of the Institute for the History of the German Jews, 21-015/327,

Collection Randt / Max Brimer.

It was no longer possible for Jews to be members of “German” sports clubs during the National Socialist regime. By 1933, all “general” sports clubs had included an “Aryan article” Arierparagraph in their statutes and excluded their Jewish members. Therefore Jews wanting to practice sports had to turn to the Jewish sports clubs. In Hamburg among other places, this initially resulted in a growth of Jewish sports clubs. In 1935, about 10% of community members are said to have been active in a Jewish sports club. The impoverishment of the Jewish population and increasing emigration eventually led to a decline in membership; nevertheless, the Jewish community continued to support the sports clubs until the prohibition of all Jewish sports clubs in 1938. Especially for many young Jews, sports had been an important means of affirming one’s Jewish identity or sometimes simply a distraction from the difficult life they faced.

Sports and sports facilities initially did not play a role during the rebuilding of Jewish communities in Germany after 1945. The main focus was on establishing the relevant religious institutions and a community center for each congregation. Yet sports continued to attract both active athletes and fans: some individuals were even able to resume their work as sports officials, such as Kurt Landauer as president of famous soccer club Bayern München. Soccer was a popular pastime in the Displaced Persons (DP) camps, and new Jewish clubs and even entire leagues were started. These dissolved in 1948, when many DPs resettled to the new state of Israel, however. A distinctly Jewish sports movement emerged again in the 1960s, when several clubs united as the Jewish sports association Makkabi Germany Maccabi Deutschland e.V. in 1965. In Hamburg it was not until 1977 that the Turn- und Sportverein Makkabi e.V. was newly founded.

Today the national Maccabi associations are still concerned with Jewish identity. Their members consider themselves part of a worldwide national-Jewish community confidently asserting itself in Israel and in the diaspora. Since 1932, the international sports event Maccabiah Games, in which top athletes compete, is held every four years. The German Maccabi association Makkabi Deutschland has been taking part again since 1969. Moreover, European Maccabi Games were established in 1929 and are also held every four years. In 2015 they were held in Berlin, the first European Maccabi Games to be held in Germany. In August 2015, Jewish athletes from all over Europe gathered at the historic location of the Olympic Games organized by the National Socialists in Berlin in order to compete and to speak out against antisemitism and racism. These 14th Maccabi Games therefore have a special, symbolic meaning in German-Jewish history, for with them, national-Jewish sports returned to the country which had ostracized and persecuted Jewish athletes after 1933.

In the area of sports there is a strong sense of Jewish identity until this day. Yet differences with other areas of leisure are beginning to disappear. The growth of the Jewish community in Germany since the 1990s not only led to its interior pluralization, but also facilitated the establishment of confident Jewish leisure time activities, from Jewish chess clubs to choirs and theater groups. Thus leisure time in general is more strongly associated with Jewish identity today than it used to be in previous decades.

This text is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution - Non commercial - No Derivatives 4.0 International License. As long as the work is unedited and you give appropriate credit according to the Recommended Citation, you may reuse and redistribute the material in any medium or format for non-commercial purposes.

Kirsten Heinsohn (Thematic Focus: Leisure and Sports), PD Dr. phil., served as Associate Professor in the Department of English, Germanic and Romance Studies at the University of Copenhagen from 2013-2015. Since 2015, she has served as Deputy Director of the Research Centre for Contemporary History in Hamburg. Her research foci comprise modern German history, German-Jewish history and gender history.

Kirsten Heinsohn, Leisure and Sports (translated by Insa Kummer), in: Key Documents of German-Jewish History, 22.09.2016. <https://dx.doi.org/10.23691/jgo:article-213.en.v1> [March 14, 2026].