The Hamburg Landungsbrücken [jetty], which afford a view of the ships coming in and going out, have always been a place where people surrendered to their maritime fantasies and longings, but also to their fears and feelings of uncertainty. When the National Socialists came to power in 1933, these positive as well as negative imaginations of the maritime world became more powerful for many German Jews, as the ships no longer served as mere symbols of freedom, but also as spaces of longing, sometimes unfulfilled.

The sixth online exhibition of Hamburg’s Key Documents of German-Jewish History therefore focuses on ships and the experiences of three individuals from Hamburg with this maritime space. Previously unpublished sources by Joseph Carlebach, Ida Dehmel and Ernst Heymann—a rabbi, an art patron and a merchant—make their three intellectual and emotional worlds during the Nazi era visible and illustrate their feelings of being torn between pleasure and dismay, joy and despair, spirit of discovery and fear of the “foreign.”

The exhibition thus opens up new perspectives—from the ship, so to speak—on the period of National Socialism and brings to mind, from an individual perspective, the destructive power of the Nazi ideology as well as the enormous resistance of the individual.

In six vertically arranged chapters, the exhibition picks out aspects of the maritime world and locates them in a general, historical context. The individual experiences, on the other hand, are traced in the horizontal stations. Together, life on board—“as on another Earth” (Ida Dehmel)—becomes visible and the ship can be experienced as a special space.

Björn Siegel and Sonja Dickow designed the exhibition. The texts were written by Carolin Vogel, Björn Siegel, Sonja Dickow and Pia Dreßler and translated by Insa Kummer. The technical implementation was carried out by Daniel Burckhardt.

These three biographies illustrate how differently the rise of National Socialism was experienced in Hamburg and how central personal history, origins and experiences with the early phase of the Nazi regime were to answering the question whether to “go or stay.”

The increasing ideological conformity [Gleichschaltung] of urban society, which was evident when Adolf Hitler visited Hamburg in 1934, for example, the formation of a so-called Aryan national community and the defamation and disenfranchisement of German Jews in the city as well as in the Reich changed the lives of these three Hamburg personalities.

The state boycotts of Jewish businesses, such as the one beginning on April 1, 1933, the exclusion of so-called non-Aryans from many professional fields and the socially acceptable, racially motivated antisemitism that was elevated to state doctrine, prompted many German Jews to emigrate. Others, however, hoped for a political change or a weakening of Nazi policies. Following the promulgation of the Nuremberg Laws of September 15, 1935, which downgraded German Jews to citizens with a lower legal status, many went into exile.

Joseph Carlebach, Ida Dehmel and Ernst Heymann also decided to leave Germany (temporarily). Until the ban on emigration in October 1941, approximately 10,000 to 12,000 Hamburg Jews left the city and fled into exile.

“The sermon became the great comforter of the Jewish people […]” (J. Carlebach, 1934)

Joseph Carlebach, born on January 30, 1883, studied at the universities of Berlin, Leipzig and Heidelberg (earning his doctorate in 1909) and at the Orthodox rabbinical seminary (Berlin). After a brief stint in the Jewish Congregation of Lübeck, he took over the Chief Rabbinate of the High German Israelite Congregation in Altona in 1925 and the Chief Rabbinate of the German Israelite Congregation of Hamburg in 1936.

Together with his wife Helene Charlotte (Lotte) Carlebach (née Preuss, married 1919), the Carlebachs’ Hamburg home formed a spiritual and social center of the Jewish Congregation. Carlebach was deeply rooted in German culture and society and hoped to combine Jewish orthodoxy and the study of the Torah with modern scholarship and contemporary education.

After 1933 he tried to oppose the Nazi regime as a spiritual leader and educator. When he received an invitation to the maiden voyage of the ship Tel Aviv from Hamburg to Haifa in 1934, he had doubts about leaving his congregation without guidance for a time. Nevertheless, he decided to join the journey, which was to take him to Mandatory Palestine and back again in 1935.

Through letters and short texts, which are kept in the archives of the Leo Baeck Institute in New York, he tried to maintain contact with his homeland.

“I have neither reason nor the right to hide the name Dehmel now.” (I. Dehmel, 1933)

Ida Dehmel, born on January 14, 1870, was well-known as an arts patron, women's rights activist and wife of the poet Richard Dehmel. In 1901 she settled in the Blankenese neighborhood. Her house became a meeting place for important artists, musicians and writers. After the death of her husband in 1920, Ida Dehmel made it into a place of remembrance, now known as the Dehmel House. In 1926, she founded the female artists' association GEDOK, which soon counted 7,000 members throughout Germany.

Although Ida Dehmel did not practice the Jewish faith and had Christian leanings, being Jewish occupied her thoughts constantly. Because of her Jewish origins, she was increasingly excluded from society during National Socialism. Despite the danger to her person, emigration was out of the question for her.

Between 1933 and 1938 Ida Dehmel took several trips on cruise ships of the Hamburg-America Line HAPAG. She traveled through the Mediterranean and around the world, seeking distraction. She always returned strengthened to the Dehmel House—a symbol of her happiness in days gone by. Records and letters are preserved in the Dehmel Archive in Hamburg.

“... as I confessed to him that I was a tanner, he decided to let go of the leather bags and returned to his embroidery work.” (E. Heymann, 1941)

Ernst Heymann was born on February 22, 1885 as the third child of a Jewish family in the largely Catholic town of Dülmen near Münster. His family owned the Heymann tannery, which had been founded in 1840 by Ernst’s grandfather Salomon. From 1899 to 1907, Ernst Heymann spent his apprenticeship years in Wolfenbüttel and Leipzig. In 1919 he moved to Elmshorn, where he oversaw the legal affairs of a leather factory.

Three years later Ernst Heymann moved to Hamburg, where he lived first on Osterstraße, then on Hagedornstraße 22. In 1925, he and his brother Paul founded the S. Heymann leather factory in Elmshorn, which brought prosperity to both.

Despite the National Socialist takeover in 1933, Ernst Heymann continued to live in Hamburg. Hoping that life in Germany would soon return to normal, he boarded a passenger ship with his wife Helene (née Werner) in 1937 and embarked on a tour of the world. Yet his desire for normality was rudely disappointed. After his return, the company Lederfabrik S. Heymann was “Aryanized” (December 1938) and taken over by Lederwerke Johann Knecht & Söhne. Facing persecution and plundering by the Nazi regime, the Heymann couple decided to flee Germany in 1941.

During their complicated emigration Ernst Heymann wrote his “Travel Journal of an Emigrant.” Both the typescript from 1941 and the handwritten travelogue from 1937 are kept in the archives of the IGdJ.

Many German Jews were deeply unsettled by the intensifying persecution measures of the Nazi regime. While some regarded the National Socialist dictatorship as a mere episode in German history and decided to stay, others fled their homeland despite the bureaucratic hurdles, the regime’s plundering measures, and the likelihood of being relegated to a lower social and economic status abroad.

Torn between the options of “leaving or staying,” travel was a welcome option for relaxation and short-term escape from the oppressive reality of the Nazi state, but also a chance to explore potential immigration possibilities in other countries. Especially those who could still afford to travel after 1933 thanks to their own financial resources undertook trips to other European and non-European countries—a fact often overlooked in research.

On the one hand, despite the goal of promoting Jewish emigration (until 1941), the Nazi regime demanded extensive guarantees from Jewish travelers to prevent its plundering measures from being undermined. On the other hand, many countries closed their borders to Jewish refugees or tightened entry formalities to prevent illegal immigration.

Until 1941, many Jews still traveled abroad, some in the hope of a better future in another country, others in the belief that they could briefly escape the terror of the Nazi regime. For many, it was a journey into the complete unknown.

In 1934 Arnold Bernstein, one of the most influential Jewish shipping company owners in Hamburg, had invited Joseph Carlebach, the well-known Orthodox Chief Rabbi of Altona, as well as Leo Baeck, the famous liberal rabbi and chairman of the Reichsvertretung der deutschen Juden [Reich Representation of German Jews], Otto Warburg, the honorary president of the Zionist World Organization, and other high-ranking Jewish representatives to take part in the maiden voyage of the Hohenstein/Tel Aviv from Hamburg via Genoa to Haifa.

The first advertising and propaganda voyage of the steamer, which was docked in the port of Hamburg, “bright and beautiful, in snow-white virginity,” still under German flag as well as the “blue-white Palestine pennant,” and belonged to the “new and first purely Jewish Palestine shipping company,” the Bernstein Palestine Shipping Company Ltd., was to turn into a very special event. The “Jewish ship,” as the Zionist newspaper Jüdische Rundschau described it, was a ray of hope for many German Jews who wanted to escape the Nazi regime. Thus, on January 26, 1935, it was seen off with great jubilation by the Jewish community of Hamburg, partly also because of the presence of Joseph Carlebach on board.

“I try to forget everything but the sea and the sun and the sky. I have nice company too. On principle, we only speak of trivial things.” (I. Dehmel, 1933)

A voucher from the Hamburg-America Line HAPAG enabled Ida Dehmel to realize her long-held wish of a sea voyage. In January 1933 she booked a ticket for the Pentecost Mediterranean cruise on board the cruise ship Oceana. Shortly after she had to resign from the chairmanship of the women artists’ association GEDOK, Dehmel, a widow, set off on her own. On May 23 the Oceana set sail from Genoa. In addition to pleasure, the cruise also promised to provide a break from political events in Hamburg.

Ida Dehmel’s closest confidante and sister, Alice Bensheimer, died in 1935. The loss weighed heavily on Ida. At the same time the restriction of personal freedom increased and the art world changed. Thanks to an inheritance, Ida Dehmel was now able to escape her situation for many months.

For the fall of 1935, she booked the Great HAPAG Orient Cruise and a voyage through the western Mediterranean on the Milwaukee. In January 1936, she boarded the Reliance in New York, on board which she traveled once around the world. In March 1937, she traveled on board the Caribia to Central America and the West Indies, and in 1938 she once again went on a tour around the world on board the Reliance. Her return to Hamburg was always certain, however.

In 1937 Helene and Ernst Heymann boarded the Dutch ship MV Marnix van Sint Aldegonde to embark on a trip around the world that took several months. While they were thus able to flee the Nazi terror for a short time, the terror started again after their return.

For this reason, Ernst Heymann and his brother Paul fled to Brussels with his family and their mother Berta even before the Heymanns’ factory was eventually “Aryanized” in December 1938. Helene Heymann, who was considered “Aryan,” stayed behind to settle the family's financial situation and followed her husband later. Brussels, however, was to be only a transit station.

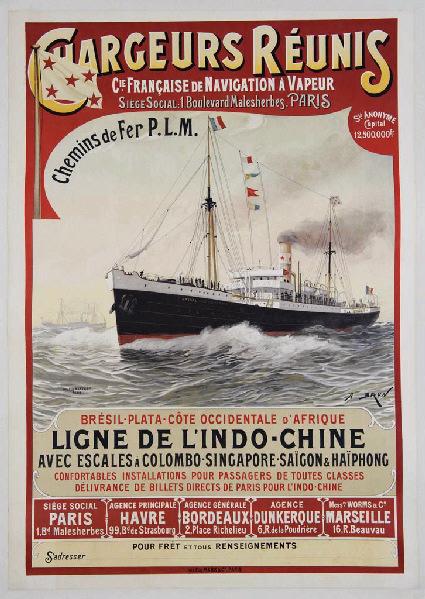

On May 23, 1941, Helene and Ernst Heymann boarded the Cap Varella, a ship owned by the French shipping company Chargeurs Réunis, in the port of Marseille. “The Cap Varella is not exactly one of the most modern ships,” Ernst Heymann noted on the first page of his diary, “with a size of approx. 8000 tons she runs about 11 to 12 nautical miles.” From Marseille they went to Algiers. Numerous stopovers followed. While Ernst Heymann initially expected a journey of two and a half months, the journey ultimately took six months. The Heymanns circumnavigated Africa on board the ship and disembarked as emigrants in Manila in the Philippines.

“To the north, the European coast is disappearing, and whether we will ever see this continent again, only the gods know.” (E. Heymann, 1941)

For many German Jews, boarding a ship in Hamburg, but also in other European ports, meant the beginning of a very special sea voyage. After they had been exposed to Nazi persecution measures, sometimes for years, the maritime and thus international space of a ship opened up the possibility for the previously persecuted, disenfranchised and excluded to become part of a temporary community once again.

On board the ships there were (still) other dividing lines, which did not follow racial categories but the different class boundaries. The Jewish passengers thus entered a maritime space which—as long as they were not on German ships—was not influenced by the ideas of an ideologically structured Nazi ethnic community. In international waters, Joseph Carlebach, Ida Dehmel, and Ernst Heymann were able to engage with their fellow passengers and their views as travelers and not necessarily as Jews, which posed a challenge for some.

The realities of a modern ship voyage—especially in first and second class—were determined by the shipping companies’ ambitions to make the ship a luxurious and extraordinary place. The promenade decks, ballrooms, smoking salons and suites were intended to provide the passengers with an adequate setting. The codex of the maritime world seemed to be detached from the actual contemporary reality that these three Hamburg personalities had experienced over the past years. Still being in possession of the funds required for such a journey, they therefore became part of a temporary community again.

“... on board the ship, people grow together like a family, and without wanting to, I, as the rabbi, am ruling the roost.” (J. Carlebach, 1935)

Joseph Carlebach considered the Hohenstein, which was renamed Tel Aviv off the coast of Genoa, to be a very special place, as the “Jewish ship” not only had a Torah in the ship’s own synagogue, it also provided ritual food in separate kosher dining rooms as well as religious educational opportunities.

Although Joseph Carlebach took advantage of the concert evenings, balls and other entertainments offered by the shipping company, which were part of the standard of any Mediterranean voyage, he believed that two “separate worlds, sometimes seemingly irreconcilable opposites” were revealed. The “carnival spirit, the joy of the ball and colorful masquerade” and the intention to “fling out of oneself the pent-up vitality in freedom” stood in opposition to the “will for contemplation, for spiritual contemplation” on the way to Mandatory Palestine or to Eretz Israel—as Carlebach wrote.

Therefore, on the journey from Hamburg to Haifa, he tried to awaken the community spirit of his mostly Jewish fellow passengers and to rekindle the faith of the non-religious among them, whom he critically referred to as “Trefo passengers,” in lectures on the Jewish faith or on the question “What is man in the face of the great sea.”

“Life aboard is ideal. My cabin is a veritable salon.” (I. Dehmel, 1935)

Ida Dehmel enjoyed the comfortable life on board the HAPAG ships. The shipping company offered its cruise ship passengers opulent meals, parties, concerts, and stage and film presentations. People played bridge, chatted, went for a walk on deck and sunbathed. The excursion program promised interesting sightseeing in the port cities and trips of several days into the interior.

After initial restraint, Ida Dehmel sought contact and conversations with fellow passengers and soon found her way. “I am getting much more comfortable. Take it easy,” she wrote to her niece in Blankenese. Richard Dehmel’s name was still well-known. As his widow she received a lot of recognition, which she enjoyed very much. Sometimes she even sat down at the captain's table or gave a lecture.

In the diary of her trips around the world on board the Reliance in 1936 and on board the Caribia in 1937, she describes above all the exotic destinations she visited on the way. She also gives accounts of observations, encounters and conversations on board, worries about the appropriateness of her evening dress and the agreeability of the food. Seemingly carefree, she and her fellow passengers devoted themselves to the daily routine of vacationers on a cruise.

“We have not yet made contact with other passengers. Undoubtedly there will be more of it than we would like. I’m already afraid of the onboard gossip.” (E. Heymann, 1941)

The long and sometimes monotonous time aboard the ship quickly brought the passengers of the Cap Varella together for different activities. “A large proportion of the passengers therefore sit from morning till late at night and play bridge with a perseverance worthy of a better cause,” Ernst Heymann noted in his travel diary in 1941.

While he and his wife avoided their fellow passengers in the beginning, the Heymann couple soon became the core of the travel party on board. In contrast to their initial intention to keep a low profile, Ernst and Helene Heymann increasingly took on social obligations for various festivities and thus became part of the “onboard gossip.”

It helped that they met neither Germans nor other emigrants on board the Cap Varella and were not exposed to reprisals or Nazi ideology. According to their own records, the Heymann couple were simply perceived as fellow passengers in 1st class. They were not regarded as persecuted or as refugees who had to leave their homeland, but as tourists. But Ernst Heymann knew that their trip to the Philippines was not for pleasure. He confessed: “but in the end this trip is not a purely tourist enterprise.”

These sea voyages made it possible not only to spend time with fellow passengers or to indulge in the wide range of entertainment on board, but also to turn to one’s own life situation. Mentally processing their own history of persecution and their experiences in National Socialist Germany during the sea voyage made the ship a place of reflection for many.

On board, Joseph Carlebach, Ida Dehmel and Ernst Heymann, who were refugees, emigrants and passengers all at the same time, were largely free to reflect on their fate. On board the ship, they were able to process Hamburg's recent transformation from an international port city to the conformist and Nazi-influenced “capital of German shipping,” which Adolf Hitler proclaimed during his visit to the Blohm & Voss shipyard in 1934. Here they could reflect on their memories of their former home town, their families and friends, but also on the experiences of antisemitism and racism of neighbors, colleagues and fellow passengers. There was room on board to search for explanations for exclusion and hatred or to seek refuge in the past or the future in order to escape reality.

The ship, this seemingly neutral place on the high seas, thus became not only a place of pleasure and distraction, but also a space for reflection on experiences in the past and each individual's hopes for the future. A place where the refugees desperately sought to discover a sense of meaning that would make it easier to bear the burden of exclusion and persecution.

“The Torah, in its preciously veiled shrine, shows the way to Erez Israel to several hundred Jewish wanderers on board a ship—indeed: this is, or rather, this was an experience worthy of the memory of coming generations.” (Israelitisches Familienblatt, 1935)

In 1935, Joseph Carlebach reflected on contemporary reality in National Socialist Germany aboard the Tel Aviv and discussed it with his fellow Jewish passengers. In his reflections he compared the situation of German Jewry after 1933 with the situation of the Jews on the eve of the so-called Reconquista of the Spanish Peninsula by Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile, which ended in the expulsion of the Jews (and Muslims) from Spain in 1492.

In spite of the exodus, his conclusion was a hopeful one, since he called the Jewish refugees from Spain “princely beggars,” who were “shown the way” by the Torah—“Queen Sabbath.” His remarks highlight how strongly Carlebach used history to cope with the present and that he saw in faith a force for overcoming persecution and exclusion even in 1935.

In texts and letters, he therefore wrote down his thoughts for the family members who had stayed at home, so that they could share his experiences on the journey and receive words of hope. These letters were his bond to the family and community in Hamburg which he did not want to see torn apart. For him, his return to Germany was beyond question, despite National Socialist persecution.

For Ida Dehmel, sea voyages meant above all distance and distraction from the oppressive situation in Germany. “One wants to leave the whole of Europe behind, one wants to be reborn,” she wrote upon her departure in Hamburg in 1935.

Instead of worrying about the past or the future, Ida Dehmel was wildly determined to enjoy all the beauties of travel. Her notes are written as reading matter for friends and family so they could share her travel experiences. She allows herself to look back only to think of her late husband and son, to recall memories of Stefan George and to give an account of a reunion with Karl Wolfskehl.

In 1935, she reported that “every captain is obliged by the management not to utter a political word, not even a greeting.” While she did not notice any antisemitism on board the Reliance in 1936, she met “followers of the Third Reich” in Costa Rica in 1937. She reflected on being German, which according to her ran “deep in the blood” and did not depend on any form of government. In 1938 she wrote from Naples, “Unfortunately I bought a German newspaper today—here one must live oblivious of the times.” Letters she received on the way also reminded her of home.

“For me personally, four or five miles would be enough, and I look forward with dread to the day when the journey ends.” (E. Heymann, 1941)

In his travel journal Ernst Heymann rarely revealed his innermost feelings and only indirectly dealt with his own emigration situation. His final entries, however, make it clear that he was afraid of having to build a new existence in a foreign country: The closer the ship came to its destination, the more he wished to be on an endless journey.

In his diary, he deliberately kept a low profile, as he had resolved “not to talk about politics and war in these notes [...].” He was much more interested in the relationships among the traveling party and the special situation aboard the ship.

While he was pleased to note that on board the Cap Varella “a strict distinction was not made,” there seemed to be invisible boundaries between the differently situated fellow passengers. At a dance event he noted: “[T]he first and second class would have preferred to go along, I think, but this would have been incompatible with dignity.”

Confronting the “here and now” that distracted him from his own life situation was Heymann's strategy for coping with his own reality of persecution.

On these sea voyages, which usually lasted several weeks, the ships called at many ports that were perceived as interesting stops on the journey. The three Hamburg personalities thus not only got to know the ship or the sea, but also the different cultures of the various port cities and their populations. In addition to dealing with their own situation of persecution, these encounters in the most diverse European, but also non-European port cities constituted a welcome change for the passengers.

In the ports, Joseph Carlebach, Ida Dehmel and Ernst Heymann met people whose appearance, languages and rituals were foreign and new in the eyes of European travelers. These experiences often allowed their reality as refugees and emigrants to recede into the background, making the three Hamburg passengers—sometimes suddenly—discoverers of other worlds and cultures.

Their ideas and judging perspectives arising from their intellectual backgrounds reflected their own cultural heritage. In addition to their middle-class notions of general education, which led them to visit world-famous places and cultural sites, it was also their partly ethnographic interest in the “foreign” and unique—here especially in Africa and Asia—that drove them and repeatedly led them into encounters.

The maiden voyage of the Tel Aviv took Joseph Carlebach to Antwerp, Lisbon and Casablanca, among other places, where he met with representatives of the local Jewish communities. Especially in Casablanca he could hardly hide his disappointment about the conditions there. In his observations, which he wrote down on board, he noted that in addition to a lack of spiritual vitality, “even in view of the frugality in the Orient—[an] unprecedented poverty and impoverishment” prevailed and hygiene was “an unknown concept in this country.”

The maiden voyage of the Tel Aviv took Joseph Carlebach to Antwerp, Lisbon and Casablanca, among other places, where he met with representatives of the local Jewish communities. Especially in Casablanca he could hardly hide his disappointment about the conditions there. In his observations, which he wrote down on board, he noted that in addition to a lack of spiritual vitality, “even in view of the frugality in the Orient—[an] unprecedented poverty and impoverishment” prevailed and hygiene was “an unknown concept in this country.”

On his journey through Palestine, he promoted the interplay of old and new, visited friends from Germany who had already emigrated to Palestine, and sought contacts with the country’s Chief Rabbinate in order to strengthen religious ties.

Getting to know foreign countries and visiting important sites was the primary purpose of the cruises Ida Dehmel booked, in addition to recreation at sea. She visited all places with the interested eye of an educated tourist. She was not looking for a new home or a safe place in the world, but for new experiences.

She recorded her most pleasant experiences, interesting observations and encounters, but also disappointments in literary descriptions. Sometimes she was enraptured with enthusiasm, as on the Caribbean island of Trinidad, in the Indian Ocean and in the cable car going up Table Mountain. Elsewhere she was disappointed: to her, New York was “terrible like all big cities” and Singapore was without contours, meanwhile she thought Hong Kong and the Forbidden City fantastic. She observed the natives with interest and admired their traditional clothing and distinguished appearance, while she was taken aback by “negroes,” “dreadful crippled beggars,” and garish American women. Ida Dehmel was glad to be German.

Her strongest impressions of all her travels were the jungle, the lush, colorful world of plants, and the realization how much she loved being at sea.

Traveling on board the Cap Varella, Helene and Ernst Heymann reached a variety of places. Their travel route took them from Marseille to North and West Africa via Madagascar and Vietnam to Manila. Their strong interest in other cultures that were foreign to the Heymann's own had already become apparent during the couple's voyage in 1937. During their flight in 1941, Ernst Heymann drew on his experiences from the previous trip and tried to deepen them by visiting “authentic” places, for example. In Algiers, he noted: “After dinner, I went alone to the city to stroll through the Kasbah, the Arab quarter.”

While Heymann often left the ship and was always open to “foreign” cultures, he invariably applied the perspective of a European who perceived the indigenous population of African countries as particularly “wild” and “uncivilized.” In Dakar, Heymann described the “miserable primitive dwellings, where negroes even still live under thatched roofs, like in a kraal.”

At the same time, however, he also reflected on his Eurocentric way of thinking, in particular criticizing France as a colonial power, which he blamed for many grievances, and he questioned the notion of European superiority.

“In my opinion, the wildest peoples today are not as dangerous as the cultured states with their registration and deregistration, residence permits, sauf-conduit [safe passage] and all the rest. With these forms you can torture people even more than if you beat them to death.” (E. Heymann, 1941)

The experiences of the long sea voyage influenced all three of the Hamburg personalities. They had used the time at sea to reflect on their own fate, to distract themselves with tourist activities, and to have discussions in which they imagined their arrival. While for some it meant reaching a new country, for others it was a return to their old home. Having arrived, they had to ask themselves various questions: How would life develop in the old or new homeland? What awaited them? And how would they be able to process the experiences?

Despite the different times and motives, all of these sea voyages were moments that took Joseph Carlebach, Ida Dehmel and Ernst Heymann out of the oppressive everyday life in National Socialist Hamburg at short notice. Their experiences of persecution and disenfranchisement receded into the background. Without knowledge of the Shoah, they left their ship, their life “as if on another Earth,” and embarked on the further course of their lives.

Two of the three, Ida Dehmel and Joseph Carlebach, returned to National Socialist Germany. Ernst Heymann, on the other hand, fled into exile in 1941 and arrived first at the transit station in the Philippines and finally in his new home. The time on board the ship remained a very special one for all three.

“If our time is a difficult and serious one for Jewry, we have learned one thing from this misery: the value of community.” (J. Carlebach, 1936)

After his return to National Socialist Germany, Joseph Carlebach told his congregation about his journey and the newly emerging Jewish life in Eretz Israel. As a representative of the Jewish Congregation of Hamburg, of which he became Chief Rabbi in 1936, he considered his experiences on the ship and in Palestine a treasure in times of growing exclusion and persecution.

The deportations in the course of the so-called Poland Action in 1938 and the destruction of the Bornplatz Synagogue during the November pogrom in the same year clearly demonstrated to Joseph Carlebach the ruthlessness and cruelty of the Nazi regime. He therefore sent five of his children abroad (one to the Mandate of Palestine and four to Great Britain). Carlebach, who would have had opportunities to emigrate in 1935 in addition to his trip to Palestine, felt a sense of obligation to his congregation and worked until the end to alleviate the hardships on the ground.

“We are about to leave for the East. We want to bid you farewell,” Carlebach wrote to his uncle in Antwerp in 1941. On December 6, 1941 he was deported to the Jungfernhof concentration camp near Riga together with his wife Charlotte and four of his children, where they were murdered on March 26, 1942.

“Floating between sea and sky is something different, it is detachment from all earthly weight.” (I. Dehmel, 1937)

Still having her travels on her mind and full of wonderful memories, Ida Dehmel resumed her life at the Dehmel House. She did not want to leave the house and its archives to fate. This was her home, and her husband and son had died for this country. She typed up her travel diaries, thought about her travels and took stock: “We live on the sea as if on another Earth.”

From 1939 on Ida Dehmel could no longer travel. The Dehmel House, which was once a sought-after address in Hamburg’s cultural life, became very quiet. Under National Socialist rule, Ida Dehmel now found herself increasingly under pressure. Although influential supporters were able to obtain exceptions and prevent her deportation, they could do nothing against inner loneliness and tormenting thoughts. In 1941 Ida Dehmel was quoted as saying: “I am now only sitting on the corner of my chair, so to speak. That I will emigrate further than to France—that is for sure. I speak every word as if it were my last.” On September 29, 1942 she took her own life, old, ill and alone.

The Dehmel House was restored and opened to visitors in 2016, the Dehmel Archive is located in the Hamburg State and University Library.

“Here, the war is unpleasantly noticeable through air raids, and the blackout is so complete that smoking is forbidden in our house even in the dark.” (E. Heymann, 1941)

At the transit station in Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam) the Heymanns obtained a visitor visa for the Philippines from the American consulate after complicated negotiations, which allowed them to reach Manila. Thanks to their friendship with a couple who was already in the Philippines, they were able to stay there instead having to emigrate further to Shanghai, which they had feared.

Nevertheless, the difficulties continued, particularly with the immigration authorities in Manila: “The chicanery of this authority lasted until the beginning of the war, and on the first day of the war I was arrested no less than three times.” In the course of the Japanese declaration of war on the Philippines in December 1941, Germans, Italians and Japanese were interned. Heymann was also arrested, but was released due to his status as a Jewish refugee. He and his wife probably experienced the further course of the Second World War in embattled Manila.

After the Second World War Ernst Heymann moved to the United States, where he died in Los Angeles on April 11, 1947. Helene Heymann returned to her home town of Hamburg. Despite extensive efforts to claim “Wiedergutmachung” [restitution and compensation], the house at Hagedornstraße 22 did not become the new center of family life. Most family members had either been deported or had emigrated via Angola or the Philippines and had found a new home in the USA. Helene Heymann, however, remained in Hamburg.

Conception: Björn Siegel and Sonja Dickow. Texts: Carolin Vogel, Björn Siegel, Sonja Dickow and Pia Dreßler. Technical Implementation: Daniel Burckhardt. Translation: Insa Kummer.

As of: April 29, 2020.