In the 1930s, the Jewish private scholar and writer Max Salzberg (1884-1954) and his wife rented an apartment on Bieberstraße. His wife Frida (1893-1993), a teacher at various girls’ schools, lived in this apartment until her death. For almost forty years after her husband’s death, she hardly made any changes, so that the memory of her husband remained omnipresent in almost all rooms.

This online exhibition makes a first attempt to highlight the biographies of Frida and Max Salzberg based on selected objects from the apartment kept at the Altona Museum today and supplemented by documents from the couple’s estate preserved in the Hamburg State Archive. At the same time, we aim to provide insights into the Jewish history of Hamburg, into everyday life and home decor during the Weimar Republic, the Nazi era and the postwar period. The exhibition’s focus is on the life and work of Max Salzberg, as the sources for researching his biography are much more favorable, probably also due to Frida’s commitment to commemorating her husband. The seven stations, arranged chronologically as far as possible, are dedicated to his childhood and youth as well as to his studies and his life and work as a private scholar. They show how the couple’s lives changed as a result of the increasing persecution during the Nazi era and how a return to a “normal” life was only possible very slowly in the postwar period. The last station takes a closer look at the history of the Salzberg collection and its significance. In addition to this thematic-chronological narrative (vertical), the individual “stations of life” (horizontal) can be explored further.

All texts were written by Hannah Rentschler. The content of the exhibition was supervised by Kirsten Heinsohn and conceived by Anna Menny.

After Frida Salzberg passed away, the heiress, Gertrud Johnsen, and her family decided to donate almost the entire inventory of the apartment to the Altona Museum. The couple’s extensive correspondence and personal papers were given to the Hamburg State Archive. Despite the great number of surviving records, the life and work of the Salzberg couple are today only known to a few. The records have barely been registered, and the collection in the Altona Museum is stored away, after an exhibition in 1998, in several depots.

The unusual collection also confronts the museum with conservation and didactic challenges: How can the various everyday objects be preserved in the long term? How can the inventory of an apartment, which itself had already been staged as a memorial site, be dealt with from the point of view of museum education? Which story(s) can be told based on the multitude of objects?

Max Salzberg was born on December 7, 1882 in Alexota/Aleksotas in Polish-Russian Lithuania, across the river from Kaunas/Kowno. With two brothers and five sisters, he grew up in poor circumstances in a difficult time. After the assassination of the Russian Tsar Alexander II in 1881, unrest and pogroms ensued. The living conditions for many Jews in Salzberg’s homeland deteriorated, and they experienced poverty, violence and persecution on a daily basis.

Salzberg’s life was marked by his traditional Orthodox parental home and his special talent for languages. At the age of three, he began to attend a Cheder to learn Hebrew.

Before and during the First World War, Max Salzberg tried to obtain Prussian citizenship. In a petition to Kaiser Wilhelm II, he also describes his origins, childhood and youth:

“I was born at Alexota near Kowno in Russia in 1882 as the son of a tailor. My parents’ great poverty did not allow them to educate me as a Talmud scholar according to their ideals. However, my love for my parents showed me the way to fulfill their wish anyway. At the age of thirteen I therefore went to a small town a few miles away from my homeland and studied there at a Talmud school under great hardships; often I had to earn the bare necessities by hard physical labor. [...] My father’s increasing poverty due to unemployment forced him to allow me to interrupt the Talmud studies for some time. I took the position of Talmud teacher in a village. In addition to the long working hours required by my twelve students of different ages, I also gave private lessons that would later allow me to travel to the foreign country I had longed for.”(Draft of a letter from Max Salzberg to Kaiser Wilhelm II for the purpose of requesting naturalization, undated, probably 1914/1915; State Archive Hamburg, 622-1/214 Salzberg, No. 1.)

Throughout his childhood and youth, Max Salzberg was strongly influenced by religion. His traditional Orthodox background on the one hand and his subsequent secular philological studies as well as his educational aspirations on the other caused conflicts of conscience. It was precisely this ambivalence that shaped Max Salzberg’s life, in which Jewish traditions always played a role, although it is unclear what significance they had in his everyday life.

In his short stories about important Jewish festivals published from 1947 on in the Jüdisches Gemeindeblatt für die britische Zonen (Jewish Community Gazette for the British Zone), Salzberg built on these childhood experiences. From the beginning of the 1950s, corresponding articles were also an integral part of the Allgemeine Wochenzeitung der Juden in Deutschland. It was founded in 1946 as the Jüdisches Gemeindeblatt für die Nord-Rheinprovinz und Westfalen (Jewish Community Gazette for the North Rhine Province and Westphalia). The first editor-in-chief and founding editor was the journalist Karl Marx, who returned to Germany in 1946 as one of the first Jewish emigrants. With the Gemeindeblatt as a licensed newspaper, he was instrumental in the rebuilding of Jewish community structures, including the Central Council of Jews in Germany. In 1948, the newspaper was initially renamed Allgemeine Wochenzeitung, which since 1955 has been published as the Allgemeine jüdische Wochenzeitung or Jüdische Allgemeine and is still the most important and highest-circulation German-Jewish newspaper.

Salzberg’s short stories reflect his extensive knowledge of Jewish customs and provide insight into the Eastern European Jewish world from which he himself came. “The Two Rabbis,” a text Salzberg wrote on the occasion of the Lag baOmer festival and which also describes the everyday life of Jewish scholars, is a case in point. Lag baOmer is a day of joy that interrupts the period of mourning between Passover and Shavuot. On this day children and adults organize picnics, and it is allowed to hold wedding ceremonies.

These prayer straps (Tefillin, also called phylacteries) can be found in the Salzberg collection in the Altona Museum. They are worn by religious Jews for the morning prayer. In the capsules attached to the straps there are pieces of parchment inscribed with texts from the Torah. A tefillin consists of a head part worn on the forehead during prayer and a hand part worn around the arm. It is unclear whether the prayer straps were used by Max Salzberg himself or by his father, for example.

The Salzberg household also included a Mezuzah. In a traditional Jewish household, such a capsule is attached to every door frame. It contains a rolled up parchment with Bible verses. The Mezuzah symbolizes the protection of God over the house and its inhabitants. It is unclear how and whether this object was used. Yet the mere fact that the objects were kept for decades testifies to the importance of such religious traditions in the life of the Salzberg couple.

Already in his youth Max Salzberg suffered from severe nearsightedness, which led to increasing retinal detachment. When he was told that he might go blind completely, he left his homeland in 1901 and went to Königsberg (Kaliningrad). Thanks to the help of financial sponsors, he was able to have an operation and follow-up treatment there, so that his condition improved initially. Three years later, however, a further deterioration set in and Salzberg traveled to Hamburg to the Israelite Hospital to seek treatment by a specialist.

In 1839 Salomon Heine made generous earmarked funds available to the German-Israelite congregation in Hamburg: this donation made it possible for the congregation to build its own hospital. The building, which was modern for its time – opened in 1843 and designed for 80 to 100 beds – was open to all patients regardless of their religious denomination. This principle was expressly formulated in the fundamental provisions, which preceded the statutes of the hospital containing a detailed set of rules. [...] While the hospital initially focused on caring for the sick, the activities of surgeon Heinrich Leisrinks (1879-1885) led to a paradigm shift: new findings in medicine led to a redefinition of the hospital’s function. Instead of caring for the sick and needy, differential medical diagnosis and treatment now became the priorities. The spectrum of operations was expanded, and a new outpatient department founded in 1880 offered consultation hours by specialists in various fields.

Prof. Dr. Richard Deutschmann was a renowned ophthalmologist who habilitated in Göttingen in 1877 and received an extraordinary professorship there in 1883. From 1899 on, he worked in the ophthalmology outpatient department at the Israelite Hospital in Hamburg. He specialized in treatment options for retinal detachment and received many awards for his achievements in research.

Beginning in February 1904, Max Salzberg began treatment with Prof. Deutschmann for two years, which did not result in any noteworthy success, however. Salzberg remained blind in one eye for the rest of his life while he could still see outlines and light conditions in the other.

His blindness and the associated restrictions did not diminish Max Salzberg’s interest in languages and his eagerness to learn. During and after the treatment at the Israelite Hospital he stayed in Hamburg and learned German, French and English mostly by teaching himself. Although he already knew Ivrit, Biblical Hebrew and Aramaic in addition to his native languages Yiddish and Russian, his aim was to become a teacher of modern languages.

.jpg) In 1909 he spent a year studying French at the Sorbonne in Paris. Back in Hamburg, he attended the Johanneum secondary school and graduated in 1913, which enabled him to take up university studies. The Johanneum, founded in 1529 as a school of scholars, is Hamburg’s oldest secondary school. Since 1802 it had been open to Jews, making it one of the first secondary schools in Germany to admit Jewish students.

In 1909 he spent a year studying French at the Sorbonne in Paris. Back in Hamburg, he attended the Johanneum secondary school and graduated in 1913, which enabled him to take up university studies. The Johanneum, founded in 1529 as a school of scholars, is Hamburg’s oldest secondary school. Since 1802 it had been open to Jews, making it one of the first secondary schools in Germany to admit Jewish students.

Max Salzberg had built up a large circle of acquaintances in Hamburg thanks to his talent for languages, including members of the important Warburg family, such as the banker and politician Max Warburg and later his daughter Gisela Warburg. With the support of some of his acquaintances, Salzberg was able to study philology at Marburg University in 1913.

In order to be able to study despite his visual impairment, Salzberg asked fellow students, such as his future wife Frida, to read texts to him. Thanks to his excellent memory, he proved to be a very good student who received much praise and support from his professors.

The good relationship with his professors was particularly advantageous for Max Salzberg after the beginning of the First World War. As a so-called “enemy alien” he was forcibly exmatriculated in 1915. After he was denied citizenship in Hamburg because of his Jewish faith, he sought naturalization in Prussia in 1914/15. In addition to Max Warburg, who issued a guarantee for Salzberg, his professors Ferdinand Wrede (professor of German) and Wilhelm Viëtor (professor of English) also supported his application with letters of reference in which they emphasized his academic achievements and extensive knowledge.

Alfred Bielschowsky, professor of ophthalmology, director of the eye clinic and co-founder of the German Academy for the Blind (Deutsche Blindenstudienanstalt) in Marburg, also spoke out in favor of Salzberg and pointed out his achievements: “Above all, however, I would like to support a possible consideration for Mr. Salzberg because he has been teaching soldiers blinded by gunshot wounds in Braille, typewriting, etc. in my clinic for many weeks now to help them through the hardest and saddest time of their lives in a way that is extremely useful for their future, and he does so on his own initiative and without taking any payment for it.” (Letter of Prof. Dr. Bielschowsky of November 30, 1914, State Archive Hamburg, 622-1/214 Salzberg, No. 1) However, the large circle of supporters could not prevent Salzberg’s application for naturalization from being rejected in 1915. It was not until August 1917 that he finally received Prussian citizenship, the reasons for which are ultimately unclear.

After re-enrolling at Marburg University, Max Salzberg received his doctorate on June 27, 1917, having written his PhD thesis on “Adjectives as a Poetic Means of Representation in Wirnt von Gravenberg with Comparative Reference to Hartmann and Wolfram.”

In his acknowledgements, he not only thanked his professors: “I would like to especially express my deepest gratitude to all my fellow students and my Hamburg friends, who helped facilitate my studies – complicated by my loss of eyesight – with the greatest human kindness.”

In 1919, he also passed the state examination for higher education in German, French and English. He then returned to Hamburg, where he continued to be enrolled for a few semesters at Hamburg University.

During his studies in Marburg Max Salzberg met his fellow student Frida Heins. She was born in 1893 in Waldheim near Hannover as the daughter of a civil servant and a woman from a wealthy upper middle-class family. In 1914 she began studying German, English and Philosophy in Freiburg and Marburg and passed her state examination in 1921. At the same time she obtained her teaching qualification for secondary schools for girls.

Around 1916 she first met Max Salzberg in a lecture and then supported him during his studies by reading him texts. In 1922 the two married and moved into an apartment in Hamburg-Wandsbek.

There is varying information about Frida Salzberg’s religious affiliation after she got married. According to the tax records of the Jewish congregation of Hamburg, she converted to Judaism. Other records state that she converted to Judaism without leaving the Lutheran Church. During the Nazi period, their marriage was treated as a “non-privileged mixed marriage” and Frida was categorized as an “Aryan woman,” so conversion seems unlikely. The marriage met with reservations on both sides among family members and friends.

Max Salzberg’s professional career proved difficult due to his blindness. Despite his successful graduation, he never managed to get a teaching job at a school. Instead, he initially worked in business while also giving lessons in modern Hebrew and Hebrew literature. From 1926 on he devoted himself exclusively to private lessons.

His extensive knowledge and language skills were in great demand in the Jewish congregation in Hamburg, especially with the increasing number of emigrants to Palestine in the 1930s. He gave language courses tailored specifically to this demand at the Franz Rosenzweig Memorial Foundation founded in Hamburg in 1930, which functioned as a school for adult education in the Jewish community. Famous Jewish personalities such as Ernst Cassirer, Max Warburg and Joseph Carlebach were involved in the foundation. (Religious) scholars also greatly valued Salzberg as an interlocutor and teacher, including Hamburg rabbi Dr. Joseph Norden, as a letter from 1939 shows:

“He [Max Salzberg] is known and highly esteemed in the broadest circles of the Hamburg community as an important expert on Hebrew literature from the biblical and Talmudic period to the present day. Young people and older men and women visit him and are enthusiastic about his teaching. [...] I myself have been coming to Dr. Salzberg for a long time for the purpose of further training in New Hebrew and always admire his extensive knowledge.” (Letter from rabbi Dr. Joseph Norden of August 14, 1939, State Archive Hamburg, 622-1/214 Salzberg, No. 38.)

Max Salzberg did not only give private lessons, he also worked as an author: he wrote numerous short stories, novellas, and several novels on religious and autobiographical topics. However, only a fraction of them was published, so that his literary work remained largely unknown.

Max Salzberg’s goal of becoming a teacher was denied him. After his return to Hamburg he was refused a placement as a trainee teacher at a state school because of his blindness. The secondary school authorities advised him to become a helper at the Talmud Tora School, but even there he was rejected because of his disability.

He made his living by working for his Jewish friend Julius Philipp . The company “Julius Philipp” was the leading importer and exporter of metals in Hamburg in the 1920s. Salzberg was responsible for foreign correspondence and acquired new knowledge in Spanish and Italian. For typing he used his “Smith Premier” typewriter, the oldest in his possession, which he had already owned during his time as a student at the Johanneum according to Frida.

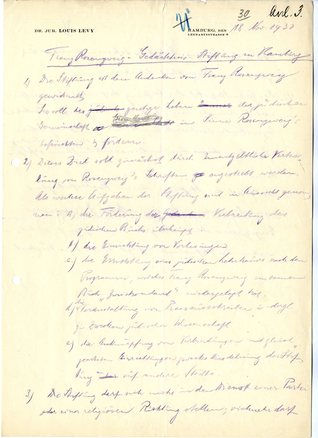

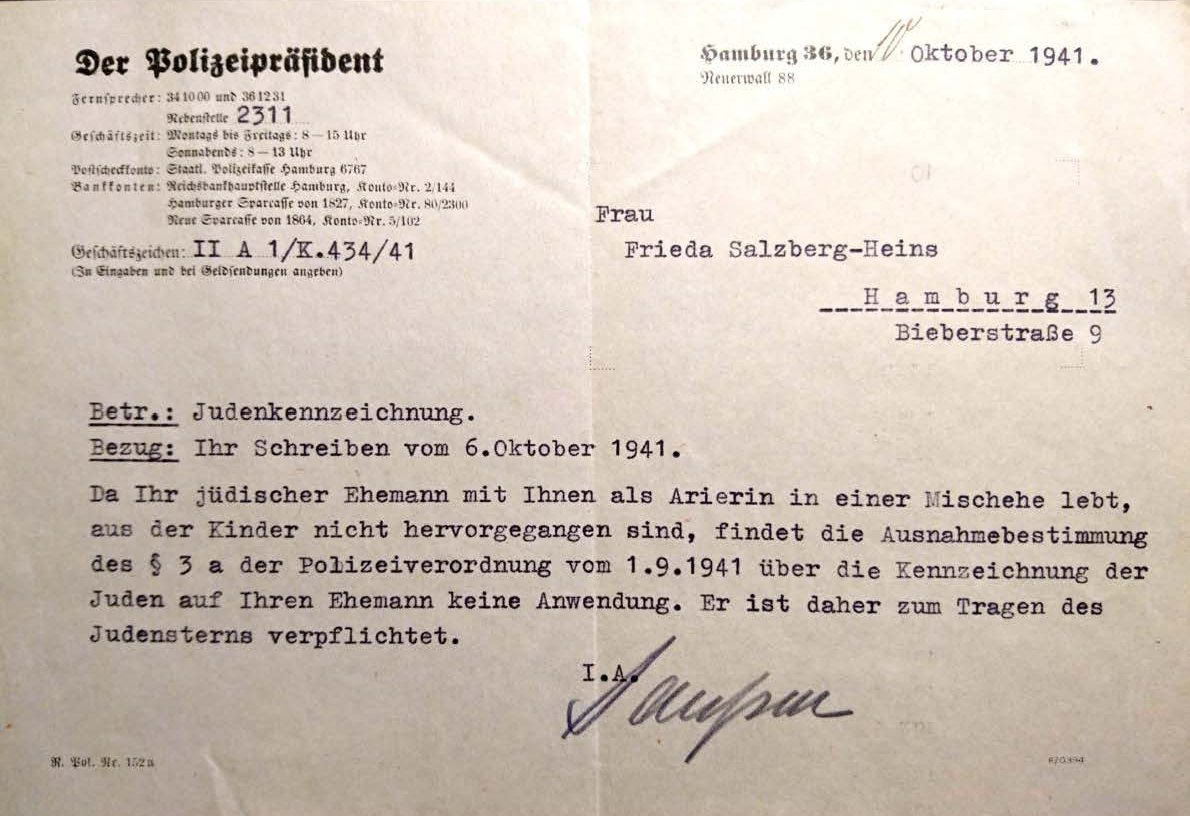

The statutes of the Franz Rosenzweig Memorial Foundation of November 1930 were kept very brief. They read like a note for the files with a five-point program. Their content combined programmatic goals and specific steps with as yet little defined institutional directives. The intellectual life of Hamburg’s Jewish community was supposed to be “stimulated and promoted according to Rosenzweig’s ideas.” Explicit reference to Rosenzweig’s book Zweistromland is made in a virtually self-obligating manner; based on his ideas a “Jewish house of teaching” was to be established in Hamburg. The foundation was supposed to be above party lines and not favor any religious movement, it was to promote the spread of Jewish books, establish a series of Jewish lectures and organize a “contest for the purposes of Jewish scholarship.” Read on >

With Hitler’s appointment as Reich Chancellor in 1933 and the ensuing antisemitic laws and ordinances, life changed drastically for the Jewish population. Jews were systematically pushed out of all areas of society. In the face of increasing exclusion and disfranchisement, Jewish education took on a new significance.

Max Salzberg was therefore in great demand as a teacher. The demand for his language lessons increased, which he gave not only at the Franz Rosenzweig Memorial Foundation, but also at the Jewish education center in Lübeck, opened in 1934. Moreover, introductory courses in the basic concepts and culture of Judaism were increasingly met with great interest. Especially those students who had grown up in families that were not religious knew little about Jewish traditions and history.

Many important personalities were taught by Salzberg in Hamburg before the Second World War, such as the Jewish historian Dr. Baruch Zwi Ophir, who studied in Hamburg, received his doctorate and emigrated to Palestine via Italy in 1933/35.

Knowledge of Hebrew and Jewish culture became particularly important for Jews who decided to emigrate to Palestine in the 1930s. Max Salzberg therefore taught special courses to prepare them for emigration.

It is impossible to give exact figures on the number of emigrated Jews due to inadequate records. In Hamburg’s urban area, there were more than 26,000 people in 1933 who were persecuted by the National Socialists regardless of their self-definition as Jews. By 1945, between 9,000 and 12,000 of them are said to have emigrated mainly to the USA, Great Britain and Palestine, most of them in 1938/39 after the November pogrom. Most likely, the number of those who emigrated was actually higher though.

Max Salzberg wrote numerous fairy tales, short stories and autobiographical sketches which clearly reflect the traditional Jewish influence in his life. Some of his short stories were published during his lifetime in Jewish newspapers such as the Jüdisches Gemeindeblatt für die britische Zone (Jewish Community Gazette for the British Zone) and the Allgemeine Wochenzeitung der Juden in Deutschland.

However, most of Max Salzberg’s literary work has remained unknown. His autobiographical novel Schurat hakawod, written in Hebrew, was published in 1951 by the publishing house “Am Owed” in Israel, thanks to personal contacts with the writer Max Brod. About 2,000 copies were sold there. Max Salzberg hoped to use the proceeds to finance a trip to Israel. However, this wish remained unfulfilled.

For other German texts, such as the novel Auf dunkler Bahn. Die Geschichte meines Lebens (On a Dark Path. The Story of My Life), in which Salzberg describes his memories of childhood and youth in Lithuania and his blindness, no publisher could be found. Only an excerpt of the novel was published in 1950 in the weekly Die Zeit. After the death of her husband, Frida Salzberg endeavored to publish his literary works. However, her attempts were unsuccessful – the publishers rejected Max Salzberg’s works because the content either did not fit the publisher’s program or the expected readership was too small. Probably on Fridas initiative, one of her acquaintances translated the first part of the novel Schurat hakawod published in Israel in 1955 into German with the title Die Ehrenreihe. Due to translation difficulties of this complex text, however, the translation was never completed. This and other unpublished manuscripts can be found in the estate of the Salzbergs located in the Hamburg State Archive.

Frida Salzberg’s career path did not run smoothly either. After her state examination in 1921, she was initially unable to find employment as a teacher, which was not unusual at the time: the crisis years of 1923/24, which were mainly caused by inflation, were marked by austerity programs that also affected schools and teachers. In Hamburg, about 630 jobs were cut in these two years. When the situation improved in 1925, the job cuts came to an end for the time being and new teachers were hired again. In 1926 Frida found employment as a senior teacher at the private higher lyceum for girls in Tesdorpfstraße 16 / Heimhuderstraße 12. She developed close contact with her students, which in some cases lasted until the end of her life. However, Frida lost her job again during National Socialism because she refused to divorce her Jewish husband. Having lost her position, she turned to giving private lessons.

Frida’s employment in 1932 also made it possible to move into a larger rented apartment: Max and Frida Salzberg moved into a seven-room apartment at Bieberstraße 9 in the Grindelviertel, which had developed into Hamburg’s main Jewish neighborhood since the turn of the century. There were not only various synagogues and prayer rooms as well as other religious institutions in the neighborhood, but also the Talmud Tora School, the Logenhaus [Meeting Hall of the Jewish Lodge] and shops for everyday needs.

During National Socialism, the Salzbergs had to struggle with many deprivations, discrimination and finally with acute threats. Since December 1938 their marriage had been categorized as a “non-privileged mixed marriage.” Marriages with a Jewish wife or Christian children were considered “privileged.” “Non-privileged” marriages, on the other hand, were childless marriages with Jewish husbands, marriages with children brought up in a Jewish manner, or marriages with previously non-Jewish spouses who converted to Judaism.

The status of “non-privileged mixed marriage” meant that the Salzbergs had to move to a “Jewish house,” their assets were frozen and Frida lost her job. Frida repeatedly tried to defend herself against the racist regulations of the Nazi regime and partly succeeded. Max Salzberg was protected by the marriage, since Jewish spouses of a “non-privileged mixed marriage” were excluded from deportations until the beginning of 1945. Although they did not manage to emigrate to the USA or Cuba, Frida and Max managed to survive in Hamburg until the end of the war despite the continuously aggravating circumstances.

With the “Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service” of April 7, 1933, as a result of which many Jews lost their jobs, Max Salzberg also lost his last hope of obtaining a job in the public school system.

The Salzberg couple were increasingly exposed to discrimination and threats as a result of the newly enacted antisemitic laws. Especially after the so-called “Nuremberg Race Laws” of 1935 were passed, the situation worsened: Max Salzberg was no longer regarded as a "citizen of the Reich" but only as a “citizen” with limited rights, as stipulated by the racist regulations. From August 1938 on, he had to adopt the additional name “Israel” like all Jewish men due to a name change ordinance, as can be seen in the employee insurance card. In October, a large red “J” was stamped in his passport.

Frida Salzberg lost her employment as a teacher and her pension claims in 1938 because she refused to divorce her Jewish husband. In the following years, she secured her income mainly by secretly giving private lessons. She was dependent on parents who entrusted their children to her although she lived in a "mixed marriage." As correspondence shows, she also taught German to the Japanese consul in Hamburg in 1942. At the beginning of the Second World War, Max Salzberg continued to give emigration courses and continued this activity until there were no more students. In the final years of the war, the couple struggled financially and lived mainly on their assets, which had been frozen by the Nazi regime, and from which they received only a certain sum each month.

Despite their own plight, the Salzbergs tried to support friends and acquaintances as much as possible and to maintain contacts. As postcards from the couple’s estate show, Leo Schneeroff asked them to send money to the Litzmannstadt ghetto in 1942. Schneeroff had been a dentist in Hamburg until his deportation in 1941 and died a few months after the Salzbergs had met his request.

The couple suffered greatly from the fact that many of their Jewish acquaintances fell victim to deportations or evaded them by suicide. Others succeeded in emigrating. Many of them did not return to Germany but kept in touch with the Salzbergs through letters.

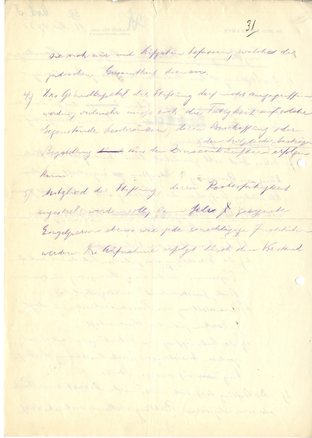

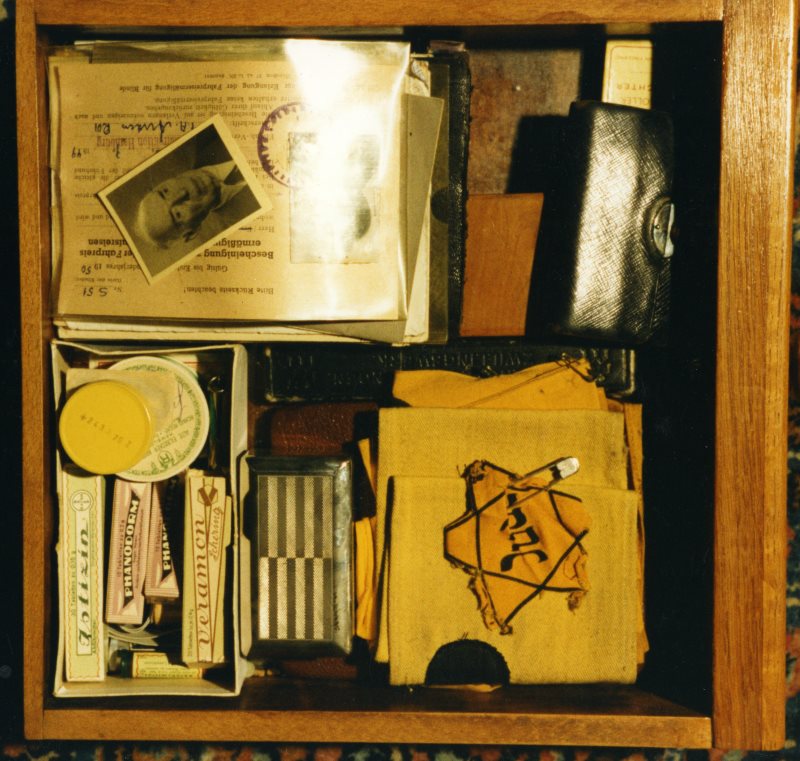

The “Police Ordinance on the Identification of Jews,” which came into force on September 1, 1941, obliged almost all Jews from the age of six to visibly wear a yellow star identifying them as Jews. Frida Salzberg tried to obtain an exception from the regulation for her husband. In October 1941, in a letter to the Hamburg Police President, she referred to § 3a of the ordinance, which provided for exceptions for Jewish spouses living in a “mixed marriage” if there were children. Since this was not the case with the Salzbergs, their application was rejected and Max Salzberg was obliged to wear the yellow star.

As can be seen in the drawer, Frida had glued the star on a strong piece of cardboard and attached a safety pin on the back. This allowed her husband to feel and put on the star independently when he wanted to leave the house. Despite the danger of discrimination in public, he initially continued to take walks.

Due to his visual impairment, Max Salzberg needed help crossing the street. In December 1941, when no one offered him help because of his yellow star, an attempt to cross the street by himself resulted in an accident in which he suffered a fractured skull and other serious injuries. Due to the accident, Max went completely blind and suffered further health problems.

Max Salzberg suffered the health consequences of the accident for the rest of his life. Over the next few years, he also experienced extreme social isolation. Since his wife worked a lot and he had no other companion, he had to stay mostly in the apartment.

However, his visual impairment also protected him to a certain extent during National Socialism. According to a document that has been found, Max Salzberg was to be arrested during the 1938 November pogroms. Due to his blindness, however, the authorities refrained from arresting him.

Nachdem zu Beginn der 1930er-Jahre noch vergleichsweise wenige Jüdinnen und Juden emigriert waren, stiegen die Auswanderungszahlen 1938/39 nach den Erfahrungen der Reichspogromnacht drastisch an. Die Salzbergs unternahmen hingegen erst nach Beginn des Zweiten Weltkrieges konkrete Versuche: Einige Geschwister von Max Salzberg waren bereits Jahrzehnte zuvor, vermutlich im Kontext des Ersten Weltkrieges, in die USA emigriert, wohin auch das Ehepaar Salzberg nun zu fliehen versuchte.

They received the necessary guarantees to be provided by a citizen of the host country not only from Max Salzberg’s relatives, but also from Gisela Warburg, Max Warburg’s daughter. He and his family had also emigrated to the USA in 1938 and had previously helped many Jews to escape, especially through financial assistance. In addition, Max and Frida received support from some remaining Hamburg acquaintances.

As correspondence and telegrams show, Gisela Warburg and one of Max Salzberg’s brothers also used personal contacts in order to enable the Salzbergs to emigrate. When the crossing to the USA turned out to be difficult, both tried to obtain a visa for Cuba for the couple. However, their efforts were unsuccessful: Shortly before the Salzbergs were able to leave Germany, an emigration ban for Jews was issued on October 23, 1941. Max Salzberg’s poor state of health due to the accident also prevented further escape plans.

Two days after the emigration ban was issued, deportations began in Hamburg. After some of their acquaintances had fallen victim to these deportations or had evaded them by committing suicide, Max Salzberg increasingly feared for his life.

In April 1942, the Salzbergs first had to vacate their apartment in Bieberstraße and were transferred by the Gestapo, along with another couple, to a smaller apartment on Grindelallee. The Reich Law on “Tenancies with Jews” of 1939 abolished the protection of tenants and the free choice of flats for Jews and made ghettoization of the Jewish population possible. Several “Jewish houses” were created in Hamburg and elsewhere, where initially “fully Jewish” people and later also those living in "non-privileged mixed marriages" were relocated. The Salzbergs had to move to the “Jewish house” at Dillstraße 15 at the end of 1942. Since Frida was ill, she tried to postpone the forced relocation, but was unsuccessful. The couple had to sell some of the furniture and household items from Bieberstraße or put them in the care of acquaintances in Hamburg and Frida’s sister in Hannover, including the dining and living room furnishings as well as Max Salzberg’s extensive library. However, a large part of their furnishings were destroyed during air raids in 1943. The Salzbergs only had what they could take with them to Dillstraße and what had been left in storage with Johann and Luise Ehlen. Johann Ehlen was a distant relative of Frida’s. The Ehlen family recalls that Luise supported the Salzberg couple during the Nazi era with food that she had delivered to Dillstraße.

In the “Jewish house” on Dillstraße, the Salzbergs had to share two rooms with eight other people. The poor supply situation and the cramped quarters caused a conflict-laden situation. As can be seen in Fridas calendar and letters, there were frequent disputes, especially because of dirt and noise.

In addition to forced relocations, the Nazi regime enacted its policy of repression by a large-sale confiscation of Jewish valuables. After Jews were forced to hand over their radios at the beginning of the war, they subsequently had to turn in all typewriters.

Frida Salzberg tried again to resist this order and asked that her husband be allowed to keep at least the Smith Premier No. 4 of his three typewriters, which had been re-equipped for his requirements: “The surrender of the latter in particular means no more and no less to my husband than if the prosthesis is taken from a one-legged man.” (Letter from Frieda Salzberg-Heins to the Jewish Religious Community Dr. Plaut of June 25, 1942, State Archive Hamburg, 622-1/214 Salzberg, No. 38) Her request was successful. Max Salzberg was allowed to keep at least one of his typewriters and recorded his memories of childhood and youth in Lithuania during the war.

Frida Salzberg wrote dates and experiences in her calendar almost daily, even during the war years. These are a rich source for the history of everyday life during National Socialisn. In addition to incisive events such as forced relocations or summonses to the Gestapo, Frida also wrote down everyday occurrences such as shopping, lessons and letters received. Her descriptions of “Operation Gomorrha,” in which a series of British and U.S. air raids from July 24 to August 3, 1943 destroyed large parts of Hamburg, are very evocative. On July 24/25 Frida wrote: “At 12:45 at night all hell broke loose: Rappstraße is on fire. All windows broken. Rutschbahn is on fire. Bornstraße on fire. Grindelallee a heap of rubble. [...] Carried water to put out the fires on Rappstraße all night long. Daylight won’t come. Full alarm in the morning [...] No more water (very little in the cellar). No more gas. No electricity. Fire brigade arriving only at 5:30 am.” (Notebook 1943 by Frida Salzberg, State Archive Hamburg, 622-1/214 Salzberg, No. 9.2 (2).)

As stipulated by the racist and antisemitic decrees, as a Jew, Max Salzberg was prohibited from using air-raid shelters during the Allied bombing raids; he and his wife had to stay in the apartment. Despite the severe destruction in the Grindelviertel they survived, and Max Salzberg was spared deportation: The Second World War ended before a planned regulation was enacted which provided for the deportation of Jewish spouses from “non-privileged mixed marriages.” Thus they were among the approximately 630 spouses in “mixed marriages” who still lived in Hamburg at the end of the war.

Some 10,000 Jews from Hamburg fell victim to the Nazi persecution and extermination policies. The few survivors who were still in Hamburg at the end of the war or who returned there were left with nothing after the end of the war. The trauma and psychological suffering were exacerbated by material hardship. Many Jews had lost a large part of their property due to the forced expropriations but, based on the British occupation zone regulations, they were treated in the same way as the rest of the German population until 1946. This meant they mostly depended on the support of welfare institutions. The policy of compensation only slowly brought about an improvement in the living conditions of the Jewish population. As early as May 1948, the “Law on Special Pensions” (Gesetz über Sonderhilfsrenten) was passed in Hamburg, which granted pensions to recognized victims of persecution. The “Law on Compensation for Wrongful Imprisonment” (Haftentschädigungsgesetz, August 1949) and Hamburg’s “General Compensation Law” (Hamburger Allgemeines Wiedergutmachungsgesetz, April 1953), which was enacted almost simultaneously with the “Federal Law for the Compensation of Victims of National Socialist Persecution” (Bundesentschädigungsgesetz), were also intended to remedy the situation. Thus Hamburg actually took on a pioneering role in the legislation.

The example of the Salzberg couple shows, however, how lengthy the process of compensation claims could be. Their applications, based on the professional discrimination suffered by Frida or the loss of furniture, books and typewriters that Max needed for his activities as a writer and private teacher, for example, were initially rejected for various reasons. A large part of the compensation payments were not made until after Max Salzberg’s death in 1954. A substantial part was only approved in the late 1950s and mid-1960s through Frida’s persistent fight for it, supported by the well-known Hamburg lawyer Herbert Pardo.

In 1950, Max Salzberg applied for compensation for imprisonment for the period in which he was obliged to wear a yellow star, which was initially denied. The decision by the Office for Compensation and Restitution states “that, in addition to the usual general restrictions imposed on the wearers of the star and resulting from the wearing of the star itself, there has to be proof of another National Socialist special restriction on personal freedom in order for the circumstances of the persons concerned to be equated with the situation of persons actually arrested and those imprisoned in a concentration camp or a ghetto.” (Decision of the Office for Compensation and Restitution on the application of Dr. Max Salzberg for compensation for imprisonment according to the “Law on Compensation for Wrongful Imprisonment” (Haftentschädigungsgesetz) of October 13, 1950, State Archive Hamburg, 622-1/214 Salzberg, No. 42)

Salzberg appealed this decision on December 11, 1950, referring to the special circumstances resulting from his blindness: “Since my wife was forced to work in those years, I had no one to accompany me. I could therefore no longer go out in the street since nobody dared to help me since I had to wear the star. On one of the first days of wearing the star I suffered a serious accident (skull fracture) while crossing the road. After that I had to stay in the dull and narrow room I lived in in a house of the Jewish community, Dillstrasse 15 until the end of the war [...]. Since I could practically no longer go out in the street, my situation was indeed the same as imprisonment.” (Letter from Max Salzberg to the Hanseatic City of Hamburg, Social Welfare Office, Office for Compensation and Restitution dated December 11, 1950, State Archive Hamburg, 622-1/214 Salzberg, No. 42 (3)) The appeal was successful, but Max Salzberg was not granted compensation until about a year later, in October 1951.

Due to their strained financial situation and the food shortages, the Salzbergs, as well as a large part of the German population, were dependent on welfare support from abroad. They also received food shipments from Jewish aid organizations, including the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JOINT). Welfare organizations such as JOINT or the British Jewish Committee for Relief Abroad were vital for the survival of Jewish displaced persons in Europe, not only organizing food supplies, but also sometimes transporting immigrants after the founding of the state of Israel.

The Salzberg couple, however, did not use the relief supplies they received only for their own needs. As before 1945, when they had helped friends and acquaintances despite their own plight, they again provided support, as can be seen from private correspondence. In May 1947, for example, a friend wrote to Frida Salzberg: “This was not the first time that you have given us such kind gifts from your parcels, but I have never experienced such help at the moment of need.” (Postcard to Frieda Salzberg Heins from May 22, 1947, Foundation Historical Museums Hamburg, Altona Museum, 1993-2172, 18.)

The experiences in the war and postwar period seem to have had such a lasting impact on Frida Salzberg in particular that she developed the need to always have supplies for times of need: 50 years later, many of the relief supplies were still unused in the Salzberg household. In the guest room, between numerous other boxes, there were about three care packages, one of them unopened.

The Salzberg couple was able to return to their rented apartment on Bieberstraße in 1945. Although the apartment had not been seriously damaged during the bombardments, living conditions proved difficult. In a letter written to an acquaintance in the postwar period, Max Salzberg reported that the apartment was “not always comfortable”: “We now often sit without heating. In the fall we had heating, but since January we have often been without heating for ten or fourteen days.” (Letter from Max Salzberg to unknown recipient, Hamburg, [October 13, 1946]; Foundation Historical Museums Hamburg, Altona Museum, 1993-2172, 16.)

In addition, correspondence and calendar entries bear witness to problems with subtenants who had probably been quartered with the Salzbergs because of the housing shortage and who, in their opinion, caused a lot of trouble. Especially their relationship with a married couple who had lived in the apartment as subtenents for three years until 1951 was extremely conflict-laden. After numerous disputes and antisemitic insults against Max, the Salzbergs went to court with an action for eviction and effected the couple’s departure in a settlement. Until at least the mid-1960s, other subtenants lived in the apartment. Probably this was due to the housing shortage in Hamburg in the postwar period. However, the exact reasons are unclear.

Frida Salzberg’s professional rehabilitation proceeded with only minor difficulties. As a result of denazification, war casualties and the large number of prisoners of war, several public service positions had become vacant. As early as 1945, Frida Salzberg was able to rejoin the teaching profession and from then on worked at the public secondary school “Oberschule für Mädchen an der Allee” in Altona. In 1946 she was appointed deputy headmistress and remained at the school until her retirement in 1959.

The Salzbergs also recalled their wartime experiences in letters to Max Salzberg’s siblings who lived in the USA. In a letter from October 1946, their losses caused by the National Socialists and the tragic circumstances of their failed emigration become clear:

“The Nazis bereft us of everything, of our money, jewelry, silver, of our wireless (which I am missing so terribly), of our woolen clothes, linen and so on, but worst of all was the deprivation of our work. […] We made all our preparations to emigrate, but in the last moment Germany closed the frontiers. Then we made an attempt to go to Cuba, but also that was in vain. The war with Russia broke out and we remained caged up among our inhuman persecutors.“

After the war, the Salzbergs received a new affidavit from one of their students and friends who had emigrated to the USA, which would have made their emigration possible. Despite the difficult situation in postwar Germany, they decided against it. According to their own statements, their fear of not being able to build a new life in a foreign country due to their advanced age and years of suffering was too great.

Not only was the everyday life of the Salzberg couple in the postwar period marked by the protracted compensation procedure. The loss of a large part of their circle of friends and acquaintances through emigration, murder or suicide due to persecution hit Max Salzberg particularly hard. Due to his disability, social contacts were important to him, as he was dependent on help for reading aloud or going for a walk. All the more important for him was the Jewish congregation in Hamburg, not least because of the importance Jewish religion and culture had in his life. With his work as a teacher of religion and Hebrew, which he resumed in the postwar period, he made an important contribution to the reconstruction of the congregation.

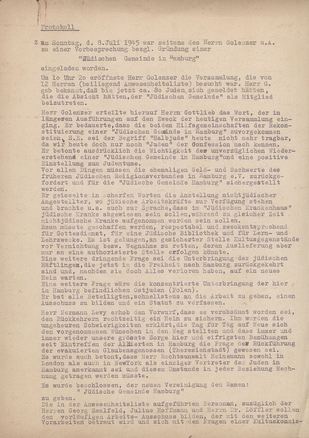

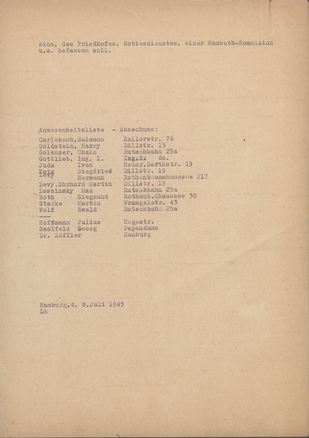

On July 8, 1945, a Sunday, twelve Hamburg Jews gathered in the apartment of Chaim Golenzer at Rutschbahn 25a, a so-called “Judenhaus,” with the intention to reorganize the congregation that had previously been eradicated by the National Socialist regime. They were all former members of Hamburg’s German-Israelite Congregation. The meeting was opened by Josef Gottlieb, who had probably initiated the founding of a new Jewish congregation in Hamburg. However, those present were not the only ones interested in a reorganization of the former congregation. The meeting’s minutes of July 8 mention roughly 80 Jews who had “been in touch.” Read on >

Max Salzberg’s teaching work made him an important part of the newly founded Jewish congregation in Hamburg in 1945. The couple was also involved in other congregation affairs. In 1949, for example, they donated to the construction of the 1933-1945 Memorial, which was erected by the Jewish congregation on the Jewish cemetery in Hamburg-Ohlsdorf.

However, his teaching work in the immediate postwar period was particularly frustrating for Max Salzberg: “I cannot report anything positive about my work. I no longer have a single student. I give two more courses in the congregation, one and a half hours a week, but they don’t satisfy me. They are children who have no interest in Hebrew, and if one or the other still wants to learn Hebrew, it meets with rejection on the part of the parents or otherwise.” (Letter from Max Salzberg to unknown recipient, Hamburg, [October 13, 1946]; Foundation Historical Museums Hamburg, Altona Museum, 1993-2172, 16.)

As some holiday photos show, in the late 1940s and early 1950s the Salzbergs were able to spend some vacations in Bad Pyrmont in order to relax and cultivate friendships. After the death of her husband, Frida also traveled to Switzerland several times for vacation.

In addition, as before and during the Second World War, the Salzberg couple maintained an active correspondence with their friends and acquaintances. Max Salzberg also maintained international contacts through the Jewish Blind Society. The extensive correspondence of the couple, consisting of letters and postcards to and from acquaintances from Germany, other European countries and the USA, is kept in the records of the Hamburg State Archive.

Influenced by the shortages during and after the war, the Salzbergs led an economical life. Smoking was one of the few pleasures that Max Salzberg enjoyed even in times of scarce tobacco rations. Several packs of cigarettes in the Salzberg household bear witness to this. The packs, which come from different countries – including Israel – as well as the extensive correspondence refer to the international support network to which the couple belonged.

The loneliness that the couple and especially Max Salzberg experienced in the postwar period due to his blindness is reflected in a letter he wrote to an acquaintance in 1946:

“Otherwise life here is very lonely for us. Of all our friends and acquaintances, nobody is here anymore. For me, loneliness is particularly difficult, because I cannot get by without people. Once a week an acquaintance reads to me from a Hebrew newspaper, "Hadawar," for an hour; this is all the connection I have with our culture.” (Letter from Max Salzberg to unknown recipient, Hamburg, [October 13, 1946]; Foundation Historical Museums Hamburg, Altona Museum, 1993-2172,16.)

Max Salzberg died on April 3, 1954 as a result of an accident he had in the couple’s apartment. He did not live to see a large part of the compensation that had only been granted in the course of the 1960s due to Frida’s inistence. Frida Salzberg herself remained in the apartment on Bieberstraße for the rest of her life and died two days after her 100th birthday in 1993. She was buried next to her husband at the Jewish cemetery in Ohlsdorf.

The close relationship Frida Salzberg maintained with many of her students deserves special mention. Some of them took special care of her in the last years of her life. In addition, there was a good relationship with the family of Luise Ehlen, the wife of Frida’s relative Johann Ehlen, who had already died in 1967. Luise Ehlen had a son from her first marriage, Gustav Johnsen. Although there was no direct relationship between Frida Salzberg and Gustav Johnsen, his wife Gertrud and their children, the close relationship continued after Luise Ehlen’s death in 1976 and eventually led to Frida appointing Gertrud Johnsen as her heir.

A few days after Max Salzberg’s death, the Allgemeine Wochenzeitung der Juden in Deutschland published an obituary on him. The obituary shows Salzberg’s great importance for the newspaper. As one of its “most loyal employees,” he reliably wrote a contribution for every Jewish holiday. These testified to his great knowledge and deep religiousness, as the obituary says. He had written his last story for the AWZdJ only a few hours before his death. In addition, the obituary emphasizes his significant contribution to the reconstruction of the Hamburg Jewish congregation, which most likely refers to his work as a teacher.

Until her death in 1993, Frida was in close contact with the descendants of Luise Ehlen, whose family had supported the Salzberg couple time and again. Probably out of gratitude for the many years of support – and since there was no other living relative – Frida bequeathed almost the entire furnishings of the apartment to Luise Ehlen’s daughter-in-law, Gertrud Johnsen, whose husband Gustav had already died in 1979.

Gertrud Johnsen and her family decided to donate most of the furniture to the Altona Museum. Her daughter, Eva Heckscher, in particular took care of the procedure and also kept the Salzberg’s records for several years. At the request of her sister Uta Seehase, they were given to the Hamburg State Archive in November 1995.

In its original state, the apartment was already a memorial site in which Frida had tried to preserve the memory of her husband. After his death, she made only a few changes. With two exhibitions at the Altona Museum and the Hamburg School Museum in 1998, the history of the Salzberg couple and the apartment furnishings were publicly exhibited for the first time. Both exhibitions were characterized by the “authenticity” of the objects and Frida’s narratives, which were put down in writing in the 1980s by Ursula Randt, a Hamburg teacher, author and historian. An academic registering and inclusion of the written records as well as an exhibition of the apartment furnishings reflecting current museum pedagogical aspects are still outstanding.

The photographs provide an insight into the Salzberg couple’s apartment at the time the furnishings were given to the Altona Museum. They show the breakfast room, parts of the kitchen and the living room. As can be seen from the photographs, the Salzberg collection encompasses every item of everyday living – from books and textiles to furniture and kitchen utensils. This complexity poses a very special challenge for the museum.

With the exception of a few memorabilia kept by the heirs and large pieces of furniture that did not find a place in the museum’s depot, the Altona Museum included the entire furnishings in its collection, where they still are today.

For Max Salzberg, the radio was an indispensable link to the outside world. It sat on its own table in the living room so that Max could always reach it from both the sofa and the chair. All the clocks in the Salzberg’s apartment were set ten minutes fast so that he could turn on the radio in time to follow the news without asking. Frida retained this habit even after his death – an important example of her attempts to preserve Max’s memory and at the same time of the stories that individual objects can tell.

The estate of the Salzberg couple also contains a box with Christmas decorations and Hanukkah utensils. Hanukkah, the Festival of Lights in memory of the cleansing of the Jerusalem Temple by the Maccabees, is one of the most important festivals in Judaism, which is celebrated for eight days in November/December. On the occasion of the festival in December 1949, Max Salzberg published a short story in the Allgemeine Wochenzeitung der Juden in Deutschland about a “stolen menorah.” Lighting the candles of the eight-armed candelabra is one of the most important festive traditions, and the Salzbergs, too, had Hanukkah candles in their household. How exactly they celebrated Christmas and Hanukkah is not known. However, it is safe to assume that religious celebrations were important for the couple.

In 1998 the Altonaer Museums showed the exhibition “Schatten. Jüdische Kultur in Altona und Hamburg“ [Shadows. Jewish Culture in Altona and Hamburg]. Part of the exhibition consisted of the Salzberg collection, which was presented to the public for the first time. Various pieces of furniture gave an insight into the everyday life of the Salzberg couple. However, a critical examination of the objects and a more thorough scholarly examination of Fridas and Max’s life story were not undertaken at the time.

At the same time, an exhibition on Jewish school life in Hamburg realized by the Hamburg School Museum took place at the Hamburg City Hall. In this exhibition Max Salzberg was also mentioned in relation to his emigration courses. In the following twenty years there has been no further (publicly perceptible) research on the Salzbergs and their legacy.

Since the first – and so far only – exhibition in 1998, the Salzberg collection has been stored in the depot of the Altona Museum. Due to a lack of financial means, it has not yet been possible to carry out a complete inventory and to make the contents accessible.

Yet individual objects of the collection are regularly integrated into current exhibitions, especially in the context of the history of everyday life.

The documents in the Hamburg State Archive were also only recently processed and made accessible for research.

Concept: Anna Menny with the support of the Altona Museum. Texts: Hannah Rentschler. Content: Kirsten Heinsohn. Technical implementation: Daniel Burckhardt. Translation: Insa Kummer.

As of: April 15, 2019.