To this day, a stone oriental carpet on the Wilhelminen Bridge in Hamburg’s Port City (Hafen City) bears witness to the former importance of the Hanseatic and port city of Hamburg as the world’s largest transshipment point for the international carpet trade. Merchants from Iran played a crucial role in settling in the warehouse district (Speicherstadt) and organizing trade in the duty-free port (Freihafen). A less well-known fact, however, is that Iranian Jews also immigrated, from the 1950s onward, to build up this economic sector and helped shape the city’s history for several decades. At the end of the 1950s, Iranian Jews formed within the still small post-war congregation a numerically significant group, characterized by a common origin and shared traditions. The exhibition entitled “We have come for free trade...” A different post-war history: The Iranian-Jewish community in Hamburg uses the example of various family histories of this group to illuminate a different Jewish post-war history, with migration and economic history intertwined and with Hamburg serving as a local and at the same time global point of reference for several decades.

In six chapters overall, the exhibition examines trade between Hamburg and Iran,

migration and trade routes, and the importance of the duty-free port in roughly

chronological order. It describes the arrival in Hamburg, the existing transnational

and local networks, and the establishment of family-run import and export companies.

The exhibition also focuses on the arrival in a city still scarred by the war and in

a Jewish community traumatized by the Holocaust and struggling with the problems of

everyday life.

The change of perspective from the first to the second generation in Chapter 4

outlines the complex question of belonging, of the perception of others and of

oneself, and provides insights into the (in)compatibilities of different lifeworlds.

Several slides refer to the impact that the 1979 Islamic Revolution had on the lives

of the families presented here, as well as on the group’s migration and trade

routes. The last two chapters are dedicated to the onward migration to the USA and

the after-effects of the Hamburg period in the families’ memories.

This online exhibition would not have been possible without the great trust placed in us by numerous people and families involved. Their stories, photos, and documents reveal – like small pieces of a mosaic – a larger picture of this largely unknown history. We would like to express special thanks to all those who gave us insights into their individual life stories as part of the interview project entitled Iranian Jews in Hamburg with interviewees in the USA, Israel, London, and Hamburg, and we would like to thank the Gerda Henkel Foundation, whose financial support made this project possible in the first place. In order to protect the personal rights of the people involved, we have decided to anonymize interview excerpts. Contrary to usual procedure, photos cannot be enlarged. All excerpts are taken from the “Iranian Jews in Hamburg” interview project, which was conducted by Dr. Karen Körber at the IGdJ and which provides the basis for this exhibition in every respect.

Hamburg began to establish itself as a trading center for what was then Persia as early as the middle of the nineteenth century. The founding of the duty-free port in 1888 and the construction of the warehouse district (Speicherstadt) allowed the storage and handling of duty-free goods and formed an essential prerequisite for the establishment of Iranian merchants. After the end of the Second World War, Germany and Iran, as it had been officially designated since 1935, established close diplomatic relations at an early stage, which were to stabilize over the coming decades and provided the framework for economic relations, which in Hamburg included to a significant extent the carpet trade. The growing group of merchants from Iran also comprised Iranian Jews who came to Hamburg from various cities in the country, such as Tehran, Urmia, Kashan, and Mashhad, in order to set up transnational family businesses together with relatives who had remained in the home country. Hamburg became a transshipment point for Iranian carpets from all parts of Iran and soon from neighboring countries in the region such as Afghanistan, India, and Nepal. Critically eyed by the local carpet industry, the “Persian carpet” developed from a luxury item to a mass product of the so-called economic miracle years, symbolizing the enthusiasm for the Orient in the young Federal Republic of Germany.

On July 23, 1857, the Hamburg diplomat (and Minister Resident) Vincent Rumpff signed a friendship and trade treaty with Persia on behalf of the three Hanseatic cities of Lübeck, Bremen, and Hamburg. With this treaty, Hamburg began to establish itself as a trading center even before Germany and Persia had signed their first treaty of friendship, trade, and shipping in 1873. After the founding of Hamburg’s duty-free port in 1888, Persian merchants settled in the warehouses of the warehouse district (Speicherstadt). In the course of the 1920s, the number of traders continued to grow. Until the beginning of the Second World War, they imported agricultural goods, cotton, and carpets and exported industrial products to Persia. In 1941, marking the death of a wholesale merchant based in Hamburg, Iranian merchants acquired an Islamic burial ground with 102 graves in the Ohlsdorf cemetery. This burial ground still exists today, having been supplemented by further Islamic burial grounds. This step at the latest marked their permanent presence in the city.

In 1952, a few years after the end of the Second World War, the Federal Republic of Germany and Iran resumed diplomatic relations. In 1955, the Iranian embassy was opened in Bonn and consulates were set up in three other cities, one of them in Hamburg. The importance of economic and political exchange between the two countries was documented by the visit of the then Shah of Persia, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, and his wife, Empress Soraya, who traveled to Germany to mark the opening. The first stop on the state visit was Hamburg. An article in the daily Die Welt reported on the imperial couple’s stay, greeted enthusiastically by Hamburg politicians and the public, and mentioned the “Persian colony” based in Hamburg in this context. The group of Iranian merchants, growing again after the end of the war, also included some Jewish traders. One of the first was Youssef Khakshouri, owner of a dried fruit factory in Urmia and active in Hamburg since 1951, where he successfully sold raisins as a sweetener to German companies. The photo shows his wife Margrit Khakshouri greeting Empress Soraya at a reception in the Hotel Atlantic.

Abdolrahim Roubeni, who arrived in Hamburg in 1959, followed by his two brothers, descended from a family already active in its third generation in the carpet trade whose trade routes extended as far as India. The Jewish traders that settled in Hamburg came from different cities across the country, such as Mashhad, Tehran, Kashan, Ishfahan, and Tabriz. The photo shows a carpet manufactory in Iran, pointing to the long tradition of craftsmanship in the country, where carpets are differentiated according to their origin from the various regions and the associated styles. In many cases, the import of carpets was part of a transnational family business. This was the case with the Roubenis, for example, who operated a large carpet warehouse in Tehran. The goods purchased in Iran, but also in Afghanistan, China, Russia, and Pakistan, were temporarily stored there and then transported by ship to Hamburg, where the Roubeni brothers took delivery of them. The Hamburg business had its storage and sales facility in the warehouse district (Speicherstadt) at Brooktorkai 5.

“Just write, we have come for free trade,” says Albert Nassimi, a Hamburg wholesaler whose father had come to Hamburg from Tehran in 1951 in search of a suitable place to trade in textiles. While some traders, including Aghajan Nassimi, had already had trade connections to Europe and Germany in Iran in the pre-war years, most of the merchants, including a growing number of Iranian Jews, only arrived in the city as the economy began to rebuild. The traders’ common destination was Hamburg’s duty-free port, which had already been declared a duty-free zone in 1888 and offered attractive opportunities for trade due to its international character, proximity to the city center, and spacious warehouses. In particular, the import and sale of carpets from Iran, which could be stored in the warehouse district (Speicherstadt), became a successful line of business that would continue to grow in the years to come. Just how dynamic the immigration of Iranians to the Hanseatic city was is illustrated by a look at the registration statistics, according to which 861 Iranian citizens were living in the city in 1958, while by 1969 their number had already risen beyond 2,000. The fact that this constituted a significant immigration group from the city’s point of view is highlighted by an internal letter from the Hamburg Senate Chancellery dating from 1956, which underlines the group’s special economic power as well as its symbolic function for the self-image of an international trading metropolis. It states, “But we are, after all, a city that lives to a large extent from its friendly relations with other countries – and also with other Muslim countries.”

Carpets from Iran were already being imported and sold in Hamburg’s warehouse district (Speicherstadt) at the beginning of the twentieth century. At that time, the trade in so-called “oriental carpets” was a business involving luxury items affordable only to a few. In contrast, the “Persian rug” became a coveted consumer item in West German living rooms during the economic miracle years in the 1960s. By 1966, around 300 carpet importers had set up shop in Hamburg’s duty-free port and some 85 percent of imported carpets came from Iran. The advertisements of Iranian carpet dealers in the Hamburg trade directory of 1963 and 1969 not only documented the growing number of traders, but also showed the success of the companies that were becoming established, including those run by Jewish Iranians. In the following years, some of the Jewish families opened their own carpet stores in Hamburg’s city center, while others supplied the carpet departments of the large department stores.

The successful carpet trade was also commented on in the German press, which pointed out that for the first time an imported product was competing with the domestic German carpet industry. As early as 1961, an article in the weekly magazine Der Spiegel noted that one in three carpets in 80 percent of Germany’s 17 million households came from Iran. Irritated, the author described a change in the street scene, where alongside German retailers, stores had set up whose façades were illuminated in the evening with suras from the Koran or oriental names such as Mohammad or Soraya in neon letters. Five years later, in 1966, the weekly newspaper Die Zeit took up the subject again. Entitled “Des Schahs liebste Kunden. Der Orient bedrängt die deutsche Teppichindustrie” (“The Shah‘s favorite customers. The Orient pressures the German carpet industry”), the article lamented a market development in which the value of imported oriental carpets was already edging close to the production of comparable goods manufactured by the German carpet industry. With clearly racist undertones, the article spoke of a “hugely swelling wave of oriental carpets” and of the potential for fraud by “dark-skinned academics” and their “rampant oriental fantasy.” The author of the text warned urgently against the “duping of the customer, the consumer-conscious German who points with restrained pride to his newly acquired brightly colored oriental carpet.” By this time, Hamburg had already become the largest carpet transshipment center in the world.

“Today, hundreds of new carpet dealers make a living from the trade in ‘people’s Persian carpets.’ Stores have sprung up in almost all major cities, with Koranic suras or oriental names such as Soraya, Mohammad, and Ahmed Ali lit up in colored neon tubes on their facades in the evening.”

During the 1950s, mainly single young men arrived in Hamburg to work in trade. They had grown up in Iran under the Pahlavi dynasty, which had modernized and secularized the country since 1925, improving the social and economic situation of the Jewish minority and making higher education accessible to Jews. Some of them had previously been in other European cities; others had already heard about the duty-free port in Iran or had a contact in the city that made their arrival easier. Among them were some whose families had been trading successfully in Iran for several generations and owned businesses, while for others emigration was an attempt to make their fortune in the post-war years. A growing network of acquaintances and relatives helped them on the ground. Establishing a business was followed by marriage, usually arranged by the families of origin in Iran, and starting a family of their own in Hamburg. Despite the good economic conditions, coming to Germany was associated with ambivalent feelings for many. After all, they arrived in the country responsible for the Holocaust just a few years after the end of the war. That event was brought home to them, particularly in the local Jewish Congregation, through encounters with survivors of the Shoah. After the Islamic Revolution in 1979, the trade and marriage migration of the 1950s and 1960s turned into refugee migration, as a result of which the Iranian community in Hamburg grew many times over.

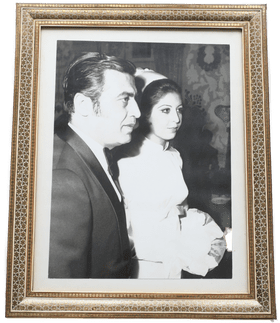

The four photographs, all taken in Hamburg about ten years apart, show a group of young men in the mid-1950s, a group of young women photographed in 1966 in the hall of the Jewish Congregation, and a photo of a number of young couples. Another picture shows the wedding of Abdi (Abdolrahman) and Rita Yaghoubi in 1967. All four photos are representative of the various migration routes by which the men and women came to Hamburg within the Iranian-Jewish trade diaspora. One example of this is the newlywed Yaghoubi couple. Abdi Yaghoubi had followed his older brother from Tehran to Hamburg in 1958 to set up an import business for carpets from Iran in the Hanseatic city. Like many other single young men, he had been sent abroad by his family, while the brothers who remained in Iran were responsible for buying and delivering the goods. After the company had been successfully established, Yaghoubi returned to Tehran in 1966 and became engaged to Rita Ghassabian. A year later, the young woman followed him to Hamburg, where the two married in the Hohe Weide synagogue. As the group photos show, the young couple did not take this step alone. In many cases, the men’s business establishment was followed by (arranged) marriage, organized by the families in the place of origin and leading to Jewish women from Iran arriving in Hamburg via the route of marriage migration and starting families there in the late 1950s and 1960s.

In the interview, Mona Nasirzadeh talks about her family’s escape from Iran after the Iranian Revolution in 1979, which led to the institution of an Islamic republic. Her father packed the picture frame with her parents’ wedding photograph from 1971 in one of the suitcases for the escape. Shortly after the violent uprising, the mother left for Israel with her three young children, while the father tried to stay in Tehran because of his business, a knitwear factory. When one of the family’s warehouses was closed under the new political leadership, Mona Nasirzadeh’s father also had to leave and the couple decided to settle in Hamburg. Their story points to the large-scale migration of people from Iran who left or had to leave the country for political, social, or religious reasons after the revolution. Like the Nasirzadeh family, many refugees turned to relatives who were already living abroad. As a result, the group of Iranians in Hamburg grew considerably. In the past, the city had mainly been a destination for those who wanted to trade or study, but within a decade, the number had increased fivefold to over 10,000 people. By then, these persons had to apply for political asylum in order to enter the country because of changes to the admission regulations between Germany and Iran. While some stayed, the city served as a transit area for others as they attempted to migrate on to the USA.

“So, the Jewish Persians who were in the carpet business naturally also had more contact with non-Jewish Persians. [...] Until the revolution, relations with the non-Jews were very close. That was very good.”

The photo from Rothenbaumchaussee 34 shows the house where Aghajan Nassimi, his wife, and their three sons moved into their first apartment in Hamburg in 1951. Youssef Khakshouri and his wife and two children also lived there for several years starting in 1953. Both families played an important role in a community in which the immigrants had to make do without the everyday connection to their families of origin and subsequently built up relationships similar to kinship among each other. This was particularly true for the group of Mashhadi Jews, who shared a sense of belonging due to their origins in the city of Mashhad and their particular history. If the group differentiated itself internally, it was part of the much larger Iranian community in Hamburg from the outset, which consisted of a growing number of traders and students and was predominantly Muslim. The Jewish and Muslim merchants met in their everyday work in the warehouse district (Speicherstadt), where they worked side by side and jointly commissioned Hamburg freight forwarders to ship and transport the carpets from Iran. However, they also met at events and celebrations organized by the Iranian consulate in the city, or at economic associations such as the German-Iranian Chamber of Commerce (Deutsch-Iranische Handelskammer e.V.), newly established in 1952.

“So I left Iran in 1952 to make my fortune in Germany of all places, in Hamburg to be precise.”

Arriving in Hamburg also meant arriving in the country responsible for the Holocaust. In his memoirs published in the early 2000s, Youssef Khakshouri writes about how difficult it was for him to move to Germany. Especially for the small group of children who attended school in Hamburg in the 1950s, it was understood that “we were not supposed to tell anyone that we were Jewish.” In the Jewish Congregation, Jews from Iran met survivors from the concentration camps, such as the executive secretary of the Congregation, Günther Singer, who had survived the Theresienstadt, Auschwitz, and Birkenau camps and lost his entire family. On behalf of many members of the second generation born in Hamburg and growing up there, one of the interviewees from the “Iranian Jews in Hamburg” project reports on how Singer’s stories shaped him and introduced him to a history that was not part of his own family experience.

“The school I went to, which was a general school, was in a place that used to be the Jewish neighborhood, but I didn´t know this at first. When I found out that it had previously been an all-girls, Jewish school, I couldn´t help wondering who sat in my chair before the war, and how many of them remained alive.”

From the very beginning, the Iranian Jews took part in the life of the Jewish Congregation in Hamburg, which was re-established in the summer of 1945 after the war. Although the Sephardic rite had applied in the synagogues in Iran, they naturally practiced the Ashkenazi rite of the post-war Hamburg Congregation and regularly attended its services. Some of the couples were among the first to celebrate their weddings in the synagogue built in 1960 on Hohe Weide; in the following decades, boys born in Hamburg were called to their bar mitzvah there. The families donated toward the needs of the synagogue and the Congregation and toward support for Israel. While the men took on religious functions and held offices on the advisory board or various committees such as the cultural, religious affairs, and finance committees, the women actively helped shape the social life of the Congregation, with many of the children attending the Congregation’s own kindergarten and later the youth club. At the same time, the group, which at one point comprised around 250 to 300 people, ensured that the traditions of their own community could also be preserved in Hamburg. This included providing kosher meat for the weekly Shabbat celebrations as well as the family celebrations and holidays, to which the families invited each other, thus strengthening social cohesion.

The letter written by Parviz Namdar in 1999 to mark the tenth anniversary of the death of the long-time executive secretary and cantor, Günther Singer, is an example of the commitment of Iranian Jews within the Hamburg Jewish Congregation. Some of the Iranian men had taken on roles in religious services at an early stage, while the women became active in social matters. As an article from Jüdische Allgemeine from 2007 shows, they were particularly involved in activities within the WIZO (Women’s International Zionist Organization) and they helped to organize the annual bazaar, not least by offering a variety of Persian dishes on the occasion. The photo taken in 1969 in the Congregation’s own kindergarten shows a group that included the first Iranian-Jewish children born in Hamburg, such as the then four-year-old Jack Morad, who later also took part in the youth club meetings. Just a few years after their arrival, in the early 1960s, some of the men also became involved in the Congregation board for the first time and took on various functions in the following decades, such as the aforementioned Parviz Namdar. He served as chairman of the Jewish Congregation’s religious affairs commission at the time of the letter shown here, an office held by Dr. Baroukh Mazloumi in 2008. Donations were also part of the group’s identity, with many families repeatedly making financial contributions, for example, toward congregational activities or maintenance work in the synagogue.

Moussa Karimzadeh’s shechita knife is a reminder of the challenges families faced in the 1950s in preserving their religious traditions after arriving in Hamburg. This included, for example, the supply of kosher meat, which could be ordered in the Jewish Congregation only at extended intervals and which was delivered from Frankfurt / Main. In order to meet the local demand in their own group, Moussa Karimzadeh initially worked as a shochet, providing kosher poultry for family celebrations and holidays. The photograph of the Nasirzadeh family putting on the mezuzah in their home in 1993 and the descriptions of the weekly Shabbat meals in the family circle also point to the importance that religious rites and practices had for the cohesion of the group in everyday life. At the same time, Iranian Jews participated in the practice of all those religious traditions and celebrations that took place within the Jewish Congregation. Many families regularly attended religious services and the children took part in the annual Purim celebrations. An important event for the boys born in Hamburg was their bar mitzvah. The photo shows Mikael Kavian and Robert Nowbakt in the Hohe Weide synagogue wearing their phylacteries and tallits [prayer belts and shawls] as they read the Torah.

In September 1976, the “Persian Jews in Hamburg” group informed the board of the Jewish Congregation that they had rented rooms in the Plaza Hotel (today the Radisson Blu) for the upcoming holidays to hold Sephardic services and that they had also organized a Persian rabbi and Sephardic prayer books for this purpose. While this part of the letter refers to the importance and cultivation of the traditions and rites brought from Iran, the rest of the letter emphasizes the connection with the Jewish Congregation in Hamburg and stresses membership. In fact, services were held in the hotel for a few weeks before the group returned to the congregational service. Conversely, the turn to their own Sephardic rite, which lasted only a short time, indicates the naturalness with which the group participated in the Ashkenazi rite of the Hamburg Congregation from the outset, in which some soon played an active role. Parviz Namdar, for example, served as a substitute cantor for many years, while Mikael Kavian relates that his father was the official Torah reader for over two decades.

Although the Iranian Jews differed from the local Jewish Congregation in many respects in terms of their religious self-image and traditions, this did not apply to the solidarity they expressed toward Israel. Some of the families had family ties to Israel; others visited the country during holidays. As a medical student, Baroukh Mazloumi was organized in the Association of Israeli-Jewish Students (Vereinigung israelisch-jüdischer Studenten), which in 1969 invited the then Israeli ambassador Asher Ben Natan to give a public lecture in the main auditorium (Audimax) of the University of Hamburg, where he was attacked by protesting students. In the following years, the group of Iranian Jews continued to document their support, for example through fundraising campaigns at the WIZO (Women’s International Zionist Organization) bazaar or through generous contributions to organizations such as Keren Kayemeth LeIsrael (KKL), thus underlining the special symbolic connection to the state of Israel.

Most of the families settled in the west of Hamburg, where the second generation grew up and attended school. They took part in the life of a big city that was initially still marked by the consequences of the war, then experienced the years of the economic miracle and, as a result, the influx of so-called “guest workers” (Gastarbeiter). Maintaining the Iranian (Jewish) traditions they had brought with them did not always prove easy; the younger generations in particular practiced the balancing act between different worlds and shared different affiliations as a matter of course. This naturalness, however, was sometimes denied to them from the outside, because racism and antisemitism were also part of the reality of life for Iranian Jews in Hamburg.

From the very beginning, everyday life of the Iranian Jews was characterized on the one hand by the cohesion of their own group and their experiences in the Jewish Congregation, and on the other hand by exchanges with the non-Jewish majority society. The photographs of social gatherings and family outings to Timmendorfer Strand beach, visits to the Christmas market and the Hamburger Dom (a large fair in Hamburg) bear witness to how the families participated in social life and leisure activities in Hamburg during the post-war decades. This also included celebrating the Persian New Year and New Year’s Eve together, in addition to the Jewish festivals and holidays. In the interview, Mona Nasirzadeh talks about how her parents made sure that they could receive and entertain guests at any time of the day and points out the special significance that such social gatherings had in the group’s self-image. Sharing meals played a central role, and the recipes for traditional Persian dishes – for which obtaining the ingredients was not always easy in Hamburg – were passed on to the next generation within the families.

“The problem was more that (...) it was made clear to me that I was different. (...) ‘Our Jewish student,’ or ‘you as a foreigner,’ I had to listen to that and so on; the fact that I was born in the place didn’t matter at all.”

Jack Morad’s school enrollment in 1971 is representative of the increasing group of second-generation Iranian Jews, born in Hamburg and mostly growing up in the west of the city. Many of the children attended one of the public schools in their neighborhood and made friends with non-Jewish peers there or at the sports club. However, growing up in a city pluralizing only slowly was not always easy. The only Jewish child in their class, they often encountered a lack of understanding when religious practices became apparent in everyday school life, such as not eating meat that was not kosher. As the accompanying quote shows, ignorance regarding elements of Jewish lifestyle was often coupled with xenophobia, which fundamentally denied that even those among them born in Hamburg belonged to the German majority society. In contrast, everyday school life was easier for those who attended the international school together as a group, which had a more heterogeneous student body. Nevertheless, many members of the second generation shared the feeling of living in two worlds. In addition to common experiences of marginalization, this was also due to the fact that the cohesion of the group, for example in the weekly Shabbat celebrations, was also binding for the second generation. The parents’ desire for their own children to grow up together with other Iranian Jews and plan their future together was central in this respect.

“We all used to have this traditional Shabbat dinner on Friday evening, we all did that throughout. Some of us might have gone out with our friends afterwards anyway. Therefore, that doesn’t mean that we sat here in the dark and didn’t watch TV. But there was indeed this tradition that Friday night is Shabbat, and that is being observed now.”

The question of their own affiliation posed a challenge for the second generation in various ways. The young Iranian Jews grew up in Hamburg in the 1970s and 1980s. They wore the fashions and hairstyles of the time, went to the movies at the UfA-Filmpalast on Gänsemarkt, and then made a detour to McDonald’s or occasionally met at the Block House restaurant, where they did not eat any meat though. They listened to “New German Wave” [Neue Deutsche Welle] and had theirs laughs about comedian Otto Waalkes and films featuring Louis de Funès. At the same time, the fact that they had multiple affiliations repeatedly caused irritation and experiences of discrimination. As Iranian Jews, they celebrated Shabbat evenings with their families and spoke Farsi with their parents, but they did not feel like a natural part of the predominantly Muslim group of Iranians living in Hamburg. Non-Jewish Germans sometimes met them with xenophobic comments based on the color of their skin or hair and they were puzzled by Jews whose own historical experience was not the Holocaust. Added to this was the legal status of the families, who held Iranian citizenship and only had a residence permit in Germany. Sonia Roubeni reluctantly remembers how she, a native of Hamburg who had never been to Iran, when requiring a new photo for her Iranian passport after the Islamic Revolution in the 1980s, was forced to wear a headscarf to this end.

The Islamic Revolution of 1979 changed the lives of the Iranian Jews in Hamburg forever. The upheaval in Iran set in motion a major exodus, which also included the families of the group living in Hamburg. While some relatives previously living in Iran arrived in Hamburg, the majority emigrated to the USA, while others went to Israel. Due to the political events in Iran, Hamburg saw growth toward the largest Iranian community in Germany. For some, the city became a transit area, while others tried to stay, which also changed the carpet trade. For many families, the altered conditions led to a reorientation within their transnational trade and family networks, often resulting in the decision to emigrate to the USA. One destination became Los Angeles, where half a million people of Iranian origin, including about 50,000 Jews, make up the largest Iranian settlement worldwide. Many of the families belonging to the group of Mashhadi Jews, whose shared history and memories created a special bond, went to Great Neck in New York, home the world’s largest Mashhadi community numbering about 10,000 people.

After the Islamic Revolution in 1979, many Jews left Iran, including almost all members of the families living in Hamburg. They were part of a growing refugee movement, as a result of which the Iranian communities already existing in the USA and Europe grew many times over. Los Angeles became the major Iranian destination in the USA, also for many Iranian Jews. In addition, Great Neck in New York developed into a place where mainly families belonging to the group of Mashhadi Jews settled. Due to the regime change in Iran, the Iranian-Jewish Diaspora in Hamburg was confronted with the fact that their trading partners based in Iran, mostly family members, gave up their businesses in order to leave the country. The revolution thus brought about changes in economic exchange relations and at the same time led to a geographical change in the existing transnational family networks. This involves a transnationality and multilingualism exemplified by the numerous congratulations from relatives to Rabin Yaghoubi on the occasion of his bar mitzvah celebration in Hamburg in 1984. While on the one hand the USA increasingly evolved into the main point of reference, on the other hand Hamburg became a place of refuge for many exiled Iranians, which also had consequences for the local carpet trade. In the second half of the 1980s, deliveries of carpets from Iran grew considerably once again, as can be seen from the 1990 report by the Hamburg State Statistical Office. At the same time, the number of carpet traders rose again and this increased the competitive pressure among local suppliers, which led to some of the Iranian-Jewish traders going out of business. These various developments resulted in a growing number of families beginning to leave Hamburg as early as the 1980s, mainly to emigrate to the USA, but also to Israel, where they invested in new business ideas. Other families stayed for the time being and bought carpets from India, Nepal, Afghanistan, and China, before the trade began collapsing in the 1990s and shrank considerably in the 2000s.

The families, most of whom left Hamburg for either Los Angeles or New York, Great Neck / USA, often met up at their destination with relatives who had emigrated there from Iran. In 1989, the Ghoulian family settled in Los Angeles, together with many others, in the Westwood district, also known as “Tehrangeles,” where a large number of Iranian stores and restaurants are located on “Persian Square,” by now officially recognized by the city administration. As a result of the Islamic Revolution, over half a million people of Iranian descent currently reside in the city, around 50,000 of whom are Iranian Jews. Hekmat and Doris Roubeni only left the city in 2002 and moved to Great Neck, a district on the Long Island peninsula and the destination of many Mashhadi Jewish families from Hamburg. Currently, it is home to the largest number of Mashhadi Jews in the USA – around 10,000 people. The community has its own religious infrastructure, including several synagogues and community centers.

Not all Iranian Jews left Hamburg. Some are still living and working in the city today. Those who were born in Hamburg pursue various professions, work in agencies, as teachers, lawyers, and engineers, or have set up their own businesses. They are still connected to the local Jewish Congregation, and some of the members of the first generation held positions there until the 2000s. They all live a transnational family life and have relatives in the USA or Israel, where they spend part of their time. For those who have moved on, Hamburg still holds (nostalgic) significance as a place where they successfully established a business and a family and as a place of childhood and youth. At the same time, the group in turn has left its mark on Hamburg. In the synagogue, Persian carpets and other donations bear witness to their active involvement. The stone oriental carpet at the entrance to Hamburg’s warehouse district (Speicherstadt) points to this important aspect of the city’s economic history, which is also the history of the Iranian Jews living in Hamburg.

Not all Iranian Jews emigrated; some stayed in Hamburg. One of them was Erik Dilmanian, who moved his carpet business from the warehouse district (Speicherstadt) to a site near the airport at the end of the 1970s, as the carpets were no longer shipped but transported by plane. Until the early 2000s, he was on the board of the Hamburg Jewish Congregation and, as head of the schools department, he played a key role in the process of founding today’s Joseph Carlebach School. Baroukh Mazloumi, who came to Germany as a medical student in the 1960s, is still practicing as a doctor in private practice in the city. Both men and their wives spend part of the year in New York, where their children have settled. Mona Nasirzadeh also lives in Hamburg and commutes to San Francisco and Los Angeles for work and for personal reasons. They are all exemplary of a transnational family life whose center of life continues to be Hamburg and which at the same time transcends national borders and great geographical distances.

“...and the life I’ve built up here, you would have had to have really good arguments to leave it.”

“So Hamburg is indeed a bit like home.”

“And we are incredibly rooted to our families. [...] I actually get homesick when I’m away. And I actually feel at home here.”

Many of the emigrated families come to Hamburg regularly. They visit the Hohe Weide synagogue, where as children they used to play hide-and-seek in the checkroom after services, go for a walk along the Outer Alster lake, and remember Hamburg’s special pastry, the Franzbrötchen. The photo dating from 2017 shows Abdi Yaghoubi with his family in the Speicherstadt warehouse district, where he is showing his two grandsons his first company headquarters. The grandchildren, born and raised in New York, call their grandparents “Oma and Opa,” one of the many examples of how life in Hamburg has left its mark on the next generation. Another example is the “Legacy” Facebook group, in which those now living in New York, Los Angeles, Milan, London, and Tel Aviv, and not least in Hamburg, have joined to exchange virtual memories of their childhood and youth in Hamburg. Many of the photographs presented here were made available by this group.

The stone oriental carpet on the Wilhelminen Bridge in Hamburg’s warehouse district (Speicherstadt) shows that not only Hamburg had a lasting impact on many of the families as a place of economic success, childhood and youth, but that the Iranian merchants also left their mark in Hamburg. The new work of art, created by Frank Raendchen in 2019, is a reminder of the history of the district, which was once the world’s largest transshipment point for carpets. There are still a few carpet dealers in the old location, where today mainly agencies, creative professionals, and restaurants have settled.

Conception: Karen Körber and Anna Menny. Texts: Karen

Körber.

Technical implementation: Anna Neovesky. Translation: Erwin Fink.

Status as of December 28, 2023.

We would like to thank the Gerda Henkel Foundation for financial support of this project.

We would like to thank the Gerda Henkel Foundation for financial support of this project.